Volume 9, Number 10—October 2003

Research

1918 Influenza Pandemic and Highly Conserved Viruses with Two Receptor-Binding Variants

Figure

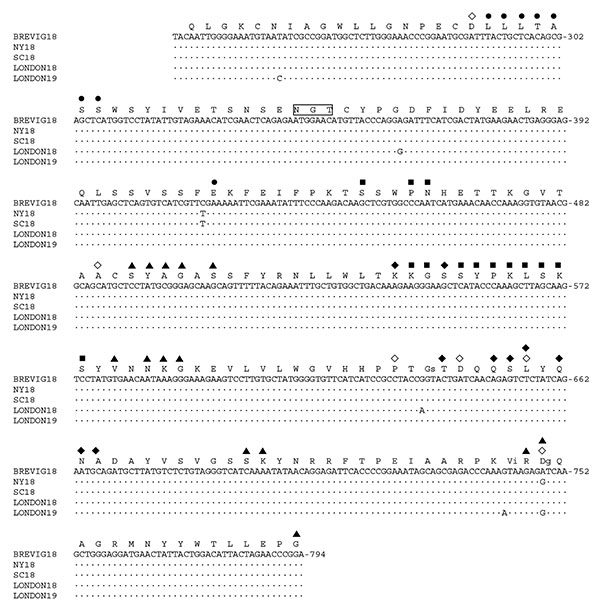

Figure. Partial HA1 domain cDNA sequences from five 1918–19 cases. A 563-bp fragment encoding antigenic (19,20) and receptor-binding (21) sites of the HA1 domain is shown, with the sequences aligned to A/Brevig Mission/1/1918 (BREVIG18) (15). Dots represent sequence identity as compared to BREVIG18. The numbering of the nucleotide sequence is aligned to A/PR/8/1934 (GenBank accession no. NC_002017) and refers to the sequence of the gene in the sense (mRNA) orientation. The partial HA1 translation product for BREVIG18 is shown above its cDNA sequence. Amino acid numbering is aligned to the H3 HA1 domain (15). Boxed amino acids indicate potential glycosylation sites as predicted by the sequence (15). Residues that have been shown experimentally to affect receptor-binding specificity in H1 HAs, D77, A138, P186, D190, L194, and D225 (21–23) are indicated by a ◇ symbol above these six residues. Residues defining four antigenic sites are indicated: Cb (●), Sa (■), Sb (◆), and Ca (▲) (19,20). Residues that have been mapped to both receptor-binding and antigenic sites (positions 194 and 225) are marked with two symbols. When a nucleotide change as compared to BREVIG18 results in a changed amino acid, the resultant amino acid is shown in lower case to the right of the BREVIG18 residue. Strain abbreviations and GenBank accession numbers: A/Brevig Mission/1/1918 (BREVIG18, # AF116575), A/South Carolina/1/1918 (SC18, # AF117241), A/New York/1/1918 (NY18, # AF116576), A/London/1/1918 (LONDON18, # AY184805), and A/London/1/1919 (LONDON19, # AY184806).

References

- Crosby A. America’s forgotten pandemic. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1989.

- Jordan E. Epidemic influenza: a survey. Chicago: American Medical Association; 1927.

- Reid AH, Taubenberger JK, Fanning TG. The 1918 Spanish influenza: integrating history and biology. Microbes Infect. 2001;3:81–7. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Taubenberger JK, Reid AH, Janczewski TA, Fanning TG. Integrating historical, clinical and molecular genetic data in order to explain the origin and virulence of the 1918 Spanish influenza virus. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2001;356:1829–39. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Patterson KD, Pyle GF. The geography and mortality of the 1918 influenza pandemic. Bull Hist Med. 1991;65:4–21.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Wright PE, Webster RG. Orthomyxoviruses. In: Knipe DM, Howley PM, editors. Fields virology. Vol 1. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2001:1533–79.

- Webster RG, Bean WJ, Gorman OT, Chambers TM, Kawaoka Y. Evolution and ecology of influenza A viruses. Microbiol Rev. 1992;56:152–79.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Lamb RA, Takeda M. Death by influenza virus protein. Nat Med. 2001;7:1286–8. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Parvin JD, Smith FI, Palese P. Rapid RNA sequencing using double-stranded template DNA, SP6 polymerase, and 3′-deoxynucleotide triphosphates. DNA. 1986;5:167–71. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Hay AJ, Gregory V, Douglas AR, Lin YP. The evolution of human influenza viruses. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2001;356:1861–70. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Influenza summary update: 2001–2 influenza season summary. June 10, 2002. [Accessed September 23, 2002]. Available from: URL: http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/diseases/flu/weeklyarchives/01-02summary.htm

- Schild GC, Oxford JS, de Jong JC, Webster RG. Evidence for host-cell selection of influenza virus antigenic variants. Nature. 1983;303:706–9. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Gambaryan A, Tuzikov A, Piskarev V, Yamnikova SS, Lvov DK, Robertson JS, Specification of receptor-binding phenotypes of influenza virus isolates from different hosts using synthetic sialylglycopolymers: non-egg-adapted human H1 and H3 influenza A and influenza B viruses share a common high binding affinity for 6′-sialyl(N-acetyllactosamine). Virology. 1997;232:345–50. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Reid AH, Fanning TG, Hultin JV, Taubenberger JK. Origin and evolution of the 1918 “Spanish” influenza virus hemagglutinin gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:1651–6. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Taubenberger JK, Reid AH, Krafft AE, Bijwaard KE, Fanning TG. Initial genetic characterization of the 1918 “Spanish” influenza virus [see comments]. Science. 1997;275:1793–6. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Winternitz MC, Wason IM, McNamara FP. The pathology of influenza. New Haven (CT): Yale University Press; 1920.

- Wolbach SB. Comments on the pathology and bacteriology of fatal influenza cases, as observed at Camp Devens, Mass. Johns Hopkins Hospital Bulletin. 1919;30:104.

- Caton AJ, Brownlee GG, Yewdell JW, Gerhard W. The antigenic structure of the influenza virus A/PR/8/34 hemagglutinin (H1 subtype). Cell. 1982;31:417–27. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Raymond F, Caton A, Cox N, Kendal AP, Brownlee GG. The antigenicity and evolution of influenza H1 haemagglutinin, from 1950–57 and 1977–1983: two pathways from one gene. Virology. 1986;148:275–87. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Matrosovich M, Gambaryan A, Teneberg S, Piskarev VE, Yamnikova SS, Lvov DK, Avian influenza A viruses differ from human viruses by recognition of sialyloigosaccharides and gangliosides and by a higher conservation of the HA receptor-binding site. Virology. 1997;233:224–34. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Rogers G, D’Souza B. Receptor binding properties of human and animal H1 influenza virus isolates. Virology. 1989;173:317–22. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Matrosovich MN, Gambaryan AS, Tuzikov AB, Byramova NE, Mochalova LV, Golbraikh AA, Probing of the receptor-binding sites of the H1 and H3 influenza A and influenza B virus hemagglutinins by synthetic and natural sialosides. Virology. 1993;196:111–21. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Matrosovich M, Tuzikov A, Bovin N, Gambaryan A, Klimov A, Castrucci MR. etal. Early alterations of the receptor-binding properties of H1, H2, and H3 avian influenza virus hemagglutinins after their introduction into mammals. J Virol. 2000;74:8502–12. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Coiras MT, Aguilar JC, Galiano M, Carlos S, Gregory V, Lin YP, Rapid molecular analysis of the haemagglutinin gene of human influenza A H3N2 viruses isolated in Spain from 1996 to 2000. Arch Virol. 2001;146:2133–47. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Macken C, Lu H, Goodman J, Boykin L. The value of a database in surveillance and vaccine selection. In: Osterhaus A, Cox N, Hampson A, editors. Options for the control of influenza IV. Amsterdam: Excerpta Medica; 2001. p. 103–6.

- Reid AH, Taubenberger JK. The 1918 flu and other influenza pandemics: “over there” and back again. Lab Invest. 1999;79:95–101.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Fosso C. Alone with death on the Tundra. In: Hedin R, Holthaus G, editors. Alaska: Reflections on land and spirit. Tucscon (AZ): University of Arizona Press; 1989. p. 215–22.

- Connor R, Kawaoka Y, Webster R, Paulson J. Receptor specificity in human, avian, and equine H2 and H3 influenza virus isolates. Virology. 1994;205:17–23. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Gensheimer KF, Fukuda K, Brammer L, Cox N, Patriarca PA, Strikes RA. Preparing for pandemic influenza: the need for enhanced surveillance. Vaccine. 2002;20(Suppl 2):S63–5. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Hayden FG. Perspectives on antiviral use during pandemic influenza. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2001;356:1877–84. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar