Volume 9, Number 4—April 2003

Dispatch

Human Neurobrucellosis with Intracerebral Granuloma Caused by a Marine Mammal Brucella spp.

Abstract

We present the first report of community-acquired human infections with marine mammal–associated Brucella spp. and describe the identification of these strains in two patients with neurobrucellosis and intracerebral granulomas. The identification of these isolates as marine mammal strains was based on omp2a sequence and amplification of the region flanking bp26.

Brucellosis, caused by intracellular gram-negative bacteria of the genus Brucella, is endemic in many areas of the world. Exposure occurs through contact with infected animals, meat, or unpasteurized milk products. Neurobrucellosis is a rare, severe form of systemic infection and has a broad range of clinical syndromes (1–3). Central nervous system Brucella granulomas have been infrequently reported in sellar and parasellar sites and in the spinal cord (4–6).

Although a number of Brucella spp. cause systemic disease in humans, they have species-specific primary reservoirs. The six recognized species of Brucella are primarily associated with terrestrial mammals and rodents. Recently, Brucella has been found to cause infections in marine mammals (7,8). An expansion of the six current nomen species of Brucella has been proposed to include one (B. maris) or two (B. pinnipediae and B. cetaceae) new nomen species to categorize these strains (7,8).

To date, only one human infection with a marine mammal strain has been reported; this infection occurred in a research laboratory worker after occupational exposure (9). We present the first report of community-acquired human infection with marine mammal–associated Brucella spp. and describe the identification of these strains from two patients with neurobrucellosis and intracerebral granulomas.

Patient 1

Patient 1 was a previously healthy, 26-year-old Peruvian man who was evaluated in July 1985 for a 3-month history of periorbital pain, headaches, and periodic generalized tonic-clonic seizures. The initial neurologic examination was nonfocal, but subsequent computerized tomography scan showed a 5x5-cm enhancing mass in the left frontoparietal region associated with midline shift.

At the time of surgical biopsy, frozen section histology raised the possibility of a high-grade astrocytoma or lymphoma, prompting resection of a 3x3-cm well-circumscribed left frontal lobe mass. Final examination of pathologic specimens showed granulomas with multinucleated giant cells (Figure 1). Bacterial, fungal, and acid-fast bacilli stains were negative. Based on these pathologic findings and concern that the patient may have had tuberculosis, treatment with isoniazid, rifampin, and ethambutol was begun. Serologic tests for Histoplasma capsulatum, Blastomyces dermatidis, Coccidioides immitis, and Paracoccidioides brasiliensis were negative. Toxoplasma gondii serologic titers were weakly positive at 1:64.

On postoperative day 39, fungal tissue cultures became positive for a Brucella spp., preliminarily identified as B. melitensis. The patient’s antimicrobial treatment was changed to tetracycline and rifampin and was continued for 2 months. An initial serologic titer for Brucella was positive at 1:160 by tube agglutination assay. A follow-up serologic titer obtained in January 1986 was negative (<1:20).

Three months before his initial evaluation, the patient had immigrated to the United States from Lima, Peru. His diet included regular consumption of unpasteurized cow or goat cheese (queso fresco) and occasional consumption of raw shellfish (ceviche). He denied eating other raw or significantly undercooked meat. He had frequently swum in the Pacific Ocean from December through March but recalled no direct contact with marine mammals.

Patient 2

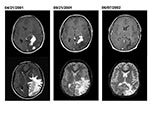

Patient 2 was a 15-year-old Peruvian boy seen in September 2001 with a 1-year history of headaches, nausea, vomiting, and progressive deterioration in visual function. A magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan performed in April 2001 showed several large, irregular enhancing mass lesions involving the left occipital and parietal lobes (Figure 2). He had come to the United States in September for further evaluation. On neurologic examination, the patient had a right homonymous hemianopsia, optic nerve atrophy, and major visual impairment (left eye—20/100; right eye—20/200). Repeat MRI showed several irregular areas of enhancement in the left parietooccipital area associated with marked brain edema, left-to-right shift, and mass effect (Figure 2).

The patient was taken to surgery, where a firm avascular mass was found beneath a 0.5-cm layer of softer gliotic cortical tissue. Frozen sections showed lymphohistiocytic infiltrates with granuloma formation. Specimens for cultures and histopathologic examination were obtained. Bacterial, fungal, and acid-fast bacilli stains were negative. Final histopathologic examination showed numerous granulomas with multinucleated giant cells but no organisms (Figure 1).

Serologic test results for Brucella, T. gondii, and Taenia soleum were negative. On postoperative day 8, mycobacteria cultures (BacT/ALERT MP; Organon Teknika Corp., Durham, NC) showed growth of a gram-negative coccobaccillus, later confirmed as Brucella spp. Treatment with rifampin, doxycycline, and intravenous gentamicin was begun. After 1 week, the gentamicin was discontinued per current recommendations, and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole was started. Follow-up imaging 7 months later demonstrated resolution of the enhancing areas and edema, with residual areas of brain atrophy (Figure 2). The patient’s vision improved, but some visual acuity deficits persisted. Anti-brucella therapy continued for 1 year.

The patient lived in a small town 7 hours from Lima and had not traveled outside of the country before coming to the United States. His diet included regular consumption of queso fresco and occasional ceviche but no other raw meats. He reported no direct contact with marine mammals and seldom visited the Peruvian coast.

Bacterial isolates were identified as Brucella spp. by using a real-time, 5′ exonuclease (TaqMan) assay, based on a well-characterized polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay that targets a highly-conserved 223-bp region of a gene (bcsp31) encoding a 31-kDa immunogenic B. abortus protein (10). Amplified product was detected through the design of a dual-labeled hybridization probe, 5′-CCGGTGCCGTTATAGGCCCAATAGG (5′, 6-carboxyfluorescein label; 3′ 6- carboxytetramethylrhodamine label). Real-time detection of amplified product was performed with a LightCycler (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN) by using the following amplification parameters: 2 min at 50°C, 10 min at 95°C, and 30 cycles of 95°C for 10 s and 60°C for 30 s. Fluorescence was monitored at 530 nm.

After identifying a bacterial isolate as Brucella spp., we attempted further classification to the species level by using real-time PCR assays to detect B. abortus, B. melitensis, and biovar 1 of B. suis (11). We used a PCR assay targeting the bp26 gene, performed as described by Cloeckaert et al. (12), to discriminate between terrestrial strains and marine mammal strains of Brucella.

Partial DNA sequencing of omp2a was also used for Brucella isolate classification (13). Amplification and sequencing of a 519-bp region of the omp2a gene were performed by using the primers 5′-GGGTGGCGAAGACGTTGACAA and 5′-AACCGTTGGCGCCCTATGC. Dye terminator cycle sequencing (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) was performed according to the manufacturer’s recommendation; the sequencing reactions were analyzed on an ABI 377 DNA sequencer.

Histopathology

Both cases demonstrated well-developed, granulomatous inflammation with accompanying astrogliosis. Patient 1 showed dense perivascular lymphoplasmacytic infiltrates with nonnecrotizing granulomas containing epithelioid and spindle-shaped macrophages and occasional well-formed giant cells (Figure 1). Tissue Gram, Fite, and silver methenamine stains showed no definite organisms. Patient 2 showed florid granulomatous inflammation with large areas of epithelioid and spindle-shaped histiocytes containing foci of necrosis surrounded by dense chronic inflammation (Figure 1). Giemsa, Steiner, Warthin-Starry, tissue Gram, Grocott methenamine silver, and Fite stains did not detect organisms. Giant cells were not observed in patient 2. Masson trichrome stain showed accompanying marked fibrosis.

Molecular Microbiology

Presumptive Brucella isolate 01A09163 was isolated from the brain biopsy of patient 2 and was submitted to the Microbial Diseases Laboratory (the microbiology reference laboratory for the State of California) for laboratory confirmation. Identification of Brucella spp. was confirmed by a 5′-exonuclease assay that targets a 223-bp region of the bcsp31 gene. Isolates confirmed as Brucella were then further classified as B. abortus, B. melitensis, or B. suis biovar 1 by the real-time PCR assays described by Redkar et al. (11). Strain 01A09163 tested negative by these assays, indicating that this isolate likely represented a different species of Brucella.

A review of Microbial Diseases Laboratory records showed a second Brucella strain, 85A05748, associated with an intracerebral granuloma. This strain was isolated in 1985 from the brain lesion of patient 1. Given the clinical similarities in these two cases, strain 85A05748 was tested by PCR. Like strain 01A09163, strain 85A05748 was negative in the B. abortus, B. melitensis, and B. suis biovar 1 assays.

To aid in the identification of these strains to the species level, a portion of the omp2a was amplified and sequenced. Between the two strains, the omp2a sequences were identical and indicated that the two strains were likely of the same species. A BLAST search of the National Center for Biotechnology Information databases established that the omp2a sequence of these two strains was identical to the omp2a sequence derived from Brucella sp. B2/94 (GenBank accession no. AF300819), a marine mammal strain of Brucella isolated from a common seal (7). Compared to other Brucella strains, one or more polymorphisms were noted in the omp2a sequence of 01A09163 and 85A05748. This observation suggested that strains 01A09163 and 85A05748 were most closely related to a marine mammal strain, rather than a terrestrial strain, of Brucella.

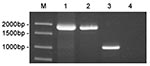

To verify that strains 01A09163 and 85A05748 were genetically related to strains of Brucella derived from marine mammals, we performed a PCR assay targeting the bp26 gene (12). Marine mammal strains of Brucella possess an IS711 element immediately downstream of bp26, whereas the sequence of terrestrial strains does not. Consequently, amplification of the region surrounding bp26 yields a much larger DNA fragment for marine mammal strains as compared to the amplification product produced by terrestrial strains of Brucella. As shown in Figure 3, amplification of the bp26 gene from strains 01A09163 and 85A05748 yielded a 1,900-bp product that was diagnostic for marine mammal strains of Brucella. Amplification of bp26 from a terrestrial strain, B. abortus, produced the expected 1,024-bp product.

Our report of serious central nervous system disease caused by a marine mammal Brucella strain confirms that these organisms can cross over from their primary hosts to humans in a community setting. Brucella infections have been documented in studies of marine mammals that died after being stranded ashore (7,8). Although a formal nomenclature has not yet been established, evidence is sufficient to support the expansion of the Brucella genus. Studies of DNA polymorphisms at the omp2 locus indicate that more than one species may be represented in this group (8). When the proposed classification scheme of Cloeckaert et al. (8) is used, partial omp2a sequence suggests that the two isolates from our study are most closely related to B. pinnipediae, a seal strain of Brucella.

Despite a more than 15-year separation, these cases have a number of epidemiologic, clinical, and histopathologic similarities. Both patients had recently immigrated from Peru. They denied significant exposure to marine mammals. Neuroimaging and pathology studies were very similar. Marked granulomatous inflammation was observed in each biopsy, but histopathologic studies did not reveal the organism in tissue sections. Definitive diagnosis was subsequently made by bacterial isolation.

Notably, Brucella spp. antibody was not elevated in patient 2. Despite his prolonged duration of illness and extensive central nervous system involvement, the patient’s steroid medications, unknown host factors, or low immunogenicity of marine mammal strains may be responsible for his lack of serologic response, emphasizing the importance of direct isolation.

Neurobrucellosis develops in <5% of patients with Brucella infection (1). The most frequent clinical syndromes associated with acute infection are meningitis or meningoencephalitis (1–3). Mass lesions within the brain parenchyma are extremely uncommon but have been documented radiographically (6) and pathologically (14). Patient 1 underwent granuloma resection before medical therapy and did not have relapse of infection. Patient 2 was treated with medical therapy. Such infections, despite widespread central nervous system extension, could possibly be treated medically, reducing potential long-term neurologic complications of resection. Furthermore, the indolent nature of these infections suggests that early detection and treatment could prevent the long-term consequences of a chronic intracranial inflammatory process.

These cases raise important issues about the epidemiology of human Brucella infection related to transmission of nonterrestrial strains. In the absence of a direct association with marine mammals, more traditional zoonotic sources of infection may be involved. Experimental infection of dairy cattle with a marine mammal strain of Brucella has been documented (15). Given the extensive Peruvian coastline, marine mammal strains of Brucella could conceivably have been transmitted to domestic animals and wildlife that reside nearby.

What degree of pathogenicity these strains may have in human infection is unclear. Further study of infection in both humans and marine mammals is needed to characterize the spectrum of disease and the potential for communicability. Such studies may be facilitated by the implementation of new laboratory tests to rapidly identify marine mammal strains of Brucella.

Dr. Sohn is a fellow in the Division of Pediatric Infectious Diseases at the University of California, San Francisco. Her research interests include the clinical and molecular epidemiology of hospital-acquired infections in high-risk pediatric populations and antimicrobial utilization and resistance.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank the faculty and staff of the microbiology laboratories of San Francisco General Hospital and the University of California, San Francisco.

References

- Shakir RA, Al-Din AS, Araj GF, Lulu AR, Mousa AR, Saadah MA. Clinical categories of neurobrucellosis: a report on 19 cases. Brain. 1987;110:213–23. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Habeeb YK, Al-Najdi AK, Sadek SA, Ol-Onaizi E. Paediatric neurobrucellosis: case report and literature review. J Infect. 1998;37:59–62. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- McLean DR, Russell N, Khan MY. Neurobrucellosis: clinical and therapeutic features. Clin Infect Dis. 1992;15:582–90.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Ceviker N, Baykaner K, Goksel M, Sener L, Alp H. Spinal cord compression due to Brucella granuloma. Infection. 1989;17:304–5. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Bingol A, Yucemen N, Meco O. Medically treated intraspinal “Brucella” granuloma. Surg Neurol. 1999;52:570–6. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Ciftci E, Erden I, Akyar S. Brucellosis of the pituitary region: MRI. Neuroradiology. 1998;40:383–4. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Jahans KL, Foster G, Broughton ES. The characterisation of Brucella strains isolated from marine mammals. Vet Microbiol. 1997;57:373–82. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Cloeckaert A, Verger JM, Grayon M, Paquet JY, Garin-Bastuji B, Foster G, Classification of Brucella spp. isolated from marine mammals by DNA polymorphism at the omp2 locus. Microbes Infect. 2001;3:729–38. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Brew SD, Perrett LL, Stack JA, MacMillan AP, Staunton NJ. Human exposure to Brucella recovered from a sea mammal. Vet Rec. 1999;24:483.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Casanas MC, Queipo-Ortuno MI, Rodriguez-Torres A, Orduna A, Colmenero JD, Morata P. Specificity of a polymerase chain reaction assay of a target sequence on the 31-kilodalton Brucella antigen DNA used to diagnose human brucellosis. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2001;20:127–31.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Redkar R, Rose S, Bricker B, DelVecchio V. Real-time detection of Brucella abortus, Brucella melitensis, and Brucella suis. Mol Cell Probes. 2001;15:43–52. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Cloeckaert A, Grayon M, Grepinet O. An IS711 element downstream of the bp26 gene is a specific marker of Brucella spp. isolated from marine mammals. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2000;7:835–9.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Ficht TA, Husseinen HS, Derr J, Bearden SW. Species-specific sequences at the omp2 locus of Brucella type strains. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1996;46:329–31. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Guven MB, Cirak B, Kutluhan A, Ugras S. Pituitary abscess secondary to neurobrucellosis: case illustration. J Neurosurg. 1999;90:1142. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Rhyan JC, Gidlewski T, Ewalt DR, Hennager SG, Lambourne DM, Olsen SC. Seroconversion and abortion in cattle experimentally infected with Brucella sp. isolated from a Pacific harbor seal (Phoca vitulina richardsi). J Vet Diagn Invest. 2001;13:379–82.PubMedGoogle Scholar

Figures

Cite This ArticleTable of Contents – Volume 9, Number 4—April 2003

| EID Search Options |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Please use the form below to submit correspondence to the authors or contact them at the following address:

Annette H. Sohn, 500 Parnassus Avenue, MU 407E, San Francisco, California 94143-0136, USA; fax: (415) 476-1343

Top