Volume 10, Number 8—August 2004

Research

Thrombocytopenia and Acute Renal Failure in Puumala Hantavirus Infections

Cite This Article

Citation for Media

Abstract

Nephropathia epidemica, caused by Puumala virus (PUUV) infection, is a form of hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome of variable severity. Early prognostic markers for the severity of renal failure have not been established. We evaluated clinical and laboratory parameters of 15 consecutive patients with acute PUUV infection, which is endemic in the Alb-Danube region, south Germany. Severe renal failure (serum creatinine >620 μmol/L) was observed in seven patients; four required hemodialysis treatment. Low platelet count (<60 x 109/L), but not leukocyte count, C-reactive protein, or other parameters obtained at the initial evaluation, was significantly associated with subsequent severe renal failure (p = 0.004). Maximum serum creatinine was preceded by platelet count nadirs by a median of 4 days. Thrombocytopenia <60 x 109/L appears predictive of a severe course of acute renal failure in nephropathia epidemica, with potential value for risk-adapted clinical disease management.

Worldwide, approximately 60,000–150,000 patients per year are hospitalized with hantavirus infections (1,2). Hantavirus spp. (Bunyaviridae family) are transmitted to humans by inhalation of aerosolized excreta of persistently infected rodents (3,4). Puumala virus (PUUV) is a representative of this genus responsible for most cases of hantavirus infections in northern Europe (1,5). The red bank vole (Clethrionomys glareolus) is the natural host reservoir of PUUV. Nephropathia epidemica attributable to acute PUUV infection is a mild form of hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome (1,4–6). Endemic seasonal outbreaks of PUUV infections are common in Scandinavia, but outbreaks in central Europe are restricted to distinct regions, e.g., in South Germany (2,4,7).

Nephropathia epidemica is characterized by acute fever, headache, nausea, vomiting, myalgia, abdominal and loin pain, mild hepatitis and pancreatitis, and interstitial nephritis with acute renal failure. Hemodialysis is required in 10% to 30% of hospitalized patients with acute PUUV infections (8). A complete recovery of renal function is regularly achieved after several weeks (1,9). Acute renal failure in nephropathia epidemica is frequently accompanied by thrombocytopenia, elevated leukocyte count, proteinuria, hematuria, and low serum calcium (9–11), but early prognostic markers have not yet been established to identify patients at high risk for a severe course of acute renal impairment. We evaluated clinical and laboratory parameters that could predict the severity of acute renal failure suitable for risk-adapted disease management in patients with nephropathia epidemica.

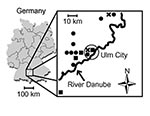

From 1998 to 2001, all consecutive patients with nephropathia epidemica and serologically confirmed hantavirus infection were studied. Patients were admitted by physicians and regional hospitals to the nephrology division of the University Hospital of Ulm, a center of nephrology and infectious diseases in south Germany with a patient base of 100 km (radius) on both sides of the River Danube. Hemodialysis was started in patients with severe symptoms of uremia (serum creatinine >620 μmol/L, serum urea nitrogen >150 mg/dL, serum potassium >6.0 mmol/L, oliguria <500 mL/day, or progressive body weight increase with edema). After discharge, a follow-up examination of all patients was conducted in our outpatient clinic. Blood pressure, leukocyte count, hemoglobin, platelet count, prothrombin time, activated partial thromboplastin time, C-reactive protein, serum electrolytes, alanine aminotransferase (ALT), serum protein, serum creatinine, urea, proteinuria, and microscopic qualitative and quantitative (Addis count) urine analysis were evaluated. Clinical and laboratory data obtained before admission were also evaluated. The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee, University of Ulm, and written informed consent was obtained from all patients. Studies were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

In all patients, acute hantavirus infection was serologically diagnosed by PUUV-specific immunoglobulin (Ig) G enzyme immunoassay (EIA) (Progen, Heidelberg, Germany). In addition, Hantaan virus (HTNV)-, PUUV- and Dobrava virus (DOBV)-specific IgM and IgG antibodies were detected by in-house monoclonal antibody–capture or μ-capture EIAs (Charité, Berlin), as previously described (12); by immunofluorescence assays (IFA) using HTNV-, PUUV-, and DOBV-infected Vero E6 cells; or by an immunoblot (IB) using recombinant hantavirus antigens (Mikrogen, Martinsried, Germany). In nine patients, hantavirus serotyping was performed by chemiluminescence focus reduction neutralization assays (c-FRNTs), as described recently (13).

Nonparametric tests were used for statistical analysis (Fisher exact test, Mann-Whitney U test), and significance was set at a level of p < 0.05. No adjustment for multiple comparisons was made, and results were interpreted in an exploratory manner. All statistical analyses were conducted with SPSS 8.0 software package (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). If not indicated otherwise, data are given as median values with range (minimum to maximum).

Fifteen patients (mean age 37 ± 8 years; male:female ratio12:3) with nephropathia epidemica were treated at the University Hospital of Ulm from January 1998 to December 2001 (Table 1). PUUV infections varied in different years by number of patients and seasons with a high incidence (Figure 1: November to December 1998: 2 patients; 1999 none; January to May 2000: 9 patients; September to November 2001: 4 patients). All but one patient lived on the North side of the River Danube. No patient was working in agriculture, forestry, or other professions considered at high risk for contact with infected rodent excreta. Acute or chronic use of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs was denied.

Patients were admitted to the hospital 5 days (range 2–10 days) after acute onset of clinical symptoms, but the first laboratory examination had already been performed 3 days (median, range 1–9 days) after onset of clinical symptoms by general practitioners. Prominent clinical and laboratory findings of acute nephropathia epidemica were fever (100%), abdominal or loin pain (80%), fatigue (67%), myalgia (60%), hepatitis (60%), headache (47%), nausea (40%), and conjunctival bleeding (20%) (Table 1). Dyspnea and pulmonary infiltrations were not observed on x-ray images. Ultrasound examination showed intact kidney forms in all patients.

PUUV-reactive IgG and IgM antibodies were detected in all patients (Table 2). EIA-positive results were confirmed by at least one independent test (in-house EIA, IFA, IB). During the acute phase of PUUV infection, cross-reactive neutralizing antibodies to other hantavirus serotypes (HTNV, Tula virus) were detected in two patients (c-FRNT), but PUUV infection was confirmed in the convalescent-phase infection by high endpoint titers for PUUV antibodies compared to other hantavirus serotypes. Because of the limited quantity of serum specimens, the complete array of virologic tests was not performed in all samples, but available serologic data demonstrated acute PUUV infections in all patients (Table 2).

In all patients, a combination of low platelet count (<150 x 109/L), elevated serum creatinine (>150 μmol/L), or elevated C-reactive protein (>10 mg/L) was detected. In seven patients (47%), severe acute renal impairment with a serum creatinine >620 μmol/L developed; four (27%) of these patients required hemodialysis as an acute intervention for 3 days (range 2–9 days) because of symptoms of uremia. During hospital stay, polyuria (>3 L/day) was present in only three patients (20%), and no patient became anuric (<500 mL/day). Serum protein was >60 g/L in all patients, plasma coagulation parameters were not altered, and mild bleeding signs (subconjunctival bleeding, petechia) were present in only three patients with a platelet count <60 x 109/L. Patients remained in the hospital for 10 days (range, 5–19 days), and follow-up examination was conducted at our outpatient clinic for 5 months (range 0.2–12.5 months).

We found that lower platelet count, higher leukocyte count, the presence of tubular cell casts in urine, quantitative hematuria and leukocyturia (Addis count), and nausea were significantly associated with severe acute renal failure (serum creatinine >620 μmol/L) (Table 1). In contrast, age, sex, blood pressure, fever, abdominal or loin pain, myalgia, headaches, fatigue, bleeding signs, hemoglobin, prothrombin time, activated partial thromboplastin time, C-reactive protein, sodium, potassium, ALT, serum protein, and proteinuria were not associated with serum creatinine >620 μmol/L (Table 1).

The platelet count nadir was observed 4 days (range 1–6 days) after the acute onset of clinical symptoms. Seven days after initial symptoms (range 3–12 days), platelet counts had already returned to normal in all patients, with values >150 x 109/L (Figure 2). Maximum serum creatinine values were observed 7 days (range 3–14 days) after onset of disease, and renal function returned to normal within 14 days (range 7–38 days) after onset of symptoms, as defined by serum creatinine <150 μmol/L.

In patients with severe renal failure, platelet count nadirs preceded maximum serum creatinine values by 4 days (range 2–10 days). In patients with a mild or severe course of acute renal failure, the platelet count was different at initial evaluation (p = 0.04), but serum creatinine values at initial evaluation did not differ (p = 0.15). We analyzed the potential prognostic value of low (<60 x 109/L) and moderately decreased (>60 x 109/L) platelet count for the severity of subsequent renal failure. This value represented the median of all patients at first evaluation, which generated two equally sized patient cohorts.

The time interval between initial clinical symptoms and first laboratory evaluation did not differ in the two groups (2 days, range 0–6 days). A platelet count of <60 x 109/L preceded severe renal failure in six of seven patients, and all patients with hemodialysis had a platelet count <60 x 109/L in the early phases of infection. Acute severe renal impairment (sensitivity 0.86, specificity 0.88, positive predictive value 0.86) developed in one of eight patients with a platelet count >60 x 109/L. The initial serum creatinine value was not different in the two groups (p = 0.54, Mann-Whitney U test), but the maximum value was significantly higher in patients with a platelet count of <60 x 109/L during the early phase of infection (Figure 3A). Although associated with a severe course of nephropathia epidemica (Table 1), an increased leukocyte count at first examination was not predictive of the severity of subsequent renal failure (Figure 3B).

Early prognostic parameters for the course of renal impairment might be beneficial for risk-adapted disease management of nephropathia epidemica, but they have not been established to date (1,14). Thrombocytopenia is a well-known transient symptom of this condition (15), and we found that severe thrombocytopenia (<60 x 109/L) was a prognostic parameter predictive for consecutive severe acute renal failure (serum creatinine >620 μmol/L).

In Germany, the hantavirus seroprevalence in humans is 1%–2%, but higher seroprevalences are found in disease-endemic regions, such as the Alb-Danube Region, south Germany (16). Most of our patients might have acquired PUUV infection during leisure activities, as occupations were not found to be risk factors in this study. Fluctuations of infected rodent populations may be responsible for the seasonal and endemic outbreaks of PUUV infections (4,6–18). Most patients with nephropathia epidemica resided to the north of the River Danube (Figure 1), which raises the possibility that the river acts as a geographic barrier for the migration of PUUV-infected rodent populations. However, direct evidence for this assumption was not provided in this study.

The diagnosis of an acute PUUV infection is established by detecting PUUV-specific IgM antibodies (19). Cross-reactive neutralizing antibodies to closely related hantavirus serotypes are common in the early but not in the convalescent phase of infection (20,21), as observed in two patients. In all patients, acute PUUV infection was proven by the different serologic tests, which were equally able to discriminate various hantavirus serotypes (Table 2).

Infections of endothelial and tubular cells, in conjunction with various immunologic mechanisms, are responsible for acute renal failure and thrombocytopenia in nephropathia epidemica. The maturation of hantavirus-infected dendritic cells may efficiently stimulate a pro-inflammatory immune response of specific T cells (22). β3 integrins are adhesive receptors on platelets, and endothelial cells may contribute to capillary leak and platelet activation in PUUV infection (3,23,24). Endothelial cell damage, circulating immune complexes, complement activation, T-cell activation, and cytokine response with high levels of tumor necrosis factor-α and interleukin-6 might cause acute renal failure and peripheral consumption of platelets (9,25,26). Similar to PUUV infections, severe thrombocytopenia may predict severe organ failure in other infectious diseases, including Rocky Mountain spotted fever (27).

In our patients, acute PUUV infection was a highly dynamic process, characterized by a short transient thrombocytopenia followed by mild-to-severe acute renal failure. We found statistical evidence that severe thrombocytopenia (<60 x 109/L) is a significant early prognostic parameter for subsequent severe acute renal failure (serum creatinine >620 μmol/L). In other studies, thrombocytopenia was not identified as a predictive marker for severe acute renal failure (9,28); in these studies, laboratory data before hospital admission were not reported (9,28). These parameters were included to evaluate the earliest phase of infection. Leukocyte count was elevated in patients with a severe course of renal failure but was not predictive at first examination (Figure 3B). Similarly, quantitative hematuria, quantitative leukocyturia, and tubular cell casts obtained 1 day (0–12 days) after admission to hospital were associated with, but not predictive for, severe renal failure.

A specific therapy for nephropathia epidemica is not generally applicable, but a symptomatic therapy including hemodialysis may be individually required. If the platelet count is <60 x 109/L in the early phase of infection, acute renal failure with serum creatinine >620 μmol/L is impending, and a tight control of clinical and laboratory parameters, including hospitalization, is mandatory. A platelet count >60 x 109/L in the early phase of infection is predictive for mild renal failure, and outpatient treatment might be possible in absence of uremia, anuria, pulmonary symptoms, or other signs of severe infection. If a patient’s platelet count has not dropped below 60 x 109/L before day 6 after initial symptoms, the clinician may feel relatively comfortable predicting that severe renal failure will not occur. Later phases of infection are characterized by increased serum creatinine values but normalizing platelet counts (Figure 2). Early dischrage from hospital may be justified in all patients at low risk for consecutive severe acute renal failure and in all patients with ongoing reconstitution of renal function. Thus, platelet counts obtained during the early phase of infection are suggested as a promising parameter for a risk-adapted, cost-effective disease management.

Dr. Rasche is a staff physician and senior scientist in the Section of Nephrology, Department of Internal Medicine II, University of Ulm, Germany. He is author of Virtual Policlinic/Docs’n Drugs, a Web-based teaching program for university medical education supported by the State Ministry of Education, and he is co-author of the Guidelines of Robert Koch Institute, Berlin. His research interests are the pathogenesis and treatment of acute and chronic renal failure.

Acknowledgments

We thank Åke Lundkvist and Matthias Niedrig for providing hantavirus strains and specific antisera for in-house tests.

The Institute of Virology (Charité) was supported by the DFG (Kr1293/2), BMBF (LTU 00/001), and Charité Medical School.

References

- Kruger DH, Ulrich R, Lundkvist A. Hantavirus infections and their prevention. Microbes Infect. 2001;3:1129–44. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Olsson GE, Dalerum F, Hornfeldt B, Elgh F, Palo RT, Juto P, Human hantavirus infections, Sweden. Emerg Infect Dis. 2003;9:1395–401.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Vapalahti O, Mustonen J, Lundkvist A, Henttonen H, Plyusnin A, Vaheri A. Hantavirus infections in Europe. Lancet Infect Dis. 2003;3:653–61. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Olsson GE, White N, Ahlm C, Elgh F, Verlemyr AC, Juto P, Demographic factors associated with hantavirus infection in bank voles (Clethrionomys glareolus). Emerg Infect Dis. 2002;8:924–9.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Faulde M, Sobe D, Kimmig P, Scharninghausen J. Renal failure and hantavirus infection in Europe. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2000;15:751–3. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Mustonen J, Vapalahti O, Henttonen H, Pasternack A, Vaheri A. Epidemiology of hantavirus infections in Europe. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1998;13:2729–31. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Clement J, Underwood P, Ward D, Pilaski J, Leduc J. Hantavirus outbreak during military manoeuvres in Germany. Lancet. 1996;347:336. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Ala-Houhala I, Koskinen M, Ahola T, Harmoinen A, Kouri T, Laurila K, Increased glomerular permeability in patients with nephropathia epidemica caused by Puumala hantavirus. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2002;17:246–52. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Mustonen J, Helin H, Pietila K, Brummer-Korvenkontio M, Hedman K, Vaheri A, Renal biopsy findings and clinicopathologic correlations in nephropathia epidemica. Clin Nephrol. 1994;41:121–6.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Saha H, Mustonen J, Pietila K, Pasternack A. Metabolism of calcium and vitamin D3 in patients with acute tubulointerstitial nephritis: a study of 41 patients with nephropathia epidemica. Nephron. 1993;63:159–63. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Settergren B. Clinical aspects of nephropathia epidemica (Puumala virus infection) in Europe: a review. Scand J Infect Dis. 2000;32:125–32. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Sibold C, Ulrich R, Labuda M, Lundkvist A, Martens H, Schutt M, Dobrava hantavirus causes hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome in central Europe and is carried by two different Apodemus mice species. J Med Virol. 2001;63:158–67. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Heider H, Ziaja B, Priemer C, Lundkvist A, Neyts J, Kruger DH, A chemiluminescence detection method of hantaviral antigens in neutralisation assays and inhibitor studies. J Virol Methods. 2001;96:17–23. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Chapman LE, Ellis BA, Koster FT, Sotir M, Ksiazek TG, Mertz GJ, Discriminators between hantavirus-infected and -uninfected persons enrolled in a trial of intravenous ribavirin for presumptive hantavirus pulmonary syndrome. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34:293–304. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Koster F, Foucar K, Hjelle B, Scott A, Chong YY, Larson R, Rapid presumptive diagnosis of hantavirus cardiopulmonary syndrome by peripheral blood smear review. Am J Clin Pathol. 2001;116:665–72. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Zoller L, Faulde M, Meisel H, Ruh B, Kimmig P, Schelling U, Seroprevalence of hantavirus antibodies in Germany as determined by a new recombinant enzyme immunoassay. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1995;14:305–13. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Escutenaire S, Chalon P, De-Jaegere F, Karelle-Bui L, Mees G, Brochier B, Behavioral, physiologic, and habitat influences on the dynamics of Puumala virus infection in bank voles (Clethrionomys glareolus). Emerg Infect Dis. 2002;8:930–6.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Sauvage F, Penalba C, Vuillaume P, Boue F, Coudrier D, Pontier D, Puumala hantavirus infection in humans and in the reservoir host, Ardennes region, France. Emerg Infect Dis. 2002;8:1509–11.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Kallio-Kokko H, Vapalahti O, Lundkvist A, Vaheri A. Evaluation of Puumala virus IgG and IgM enzyme immunoassays based on recombinant baculovirus-expressed nucleocapsid protein for early nephropathia epidemica diagnosis. Clin Diagn Virol. 1998;10:83–90. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Schutt M, Gerke P, Meisel H, Ulrich R, Kruger DH. Clinical characterization of Dobrava hantavirus infections in Germany. Clin Nephrol. 2001;55:371–4.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Lundkvist A, Hukic M, Horling J, Gilljam M, Nichol S, Niklasson B. Puumala and Dobrava viruses cause hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome in Bosnia-Herzegovina: evidence of highly cross-neutralizing antibody responses in early patient sera. J Med Virol. 1997;53:51–9. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Raftery MJ, Kraus AA, Ulrich R, Kruger DH, Schonrich G. Hantavirus infection of dendritic cells. J Virol. 2002;76:10724–33. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Mackow ER, Gavrilovskaya IN. Cellular receptors and hantavirus pathogenesis. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2001;256:91–115.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Geimonen E, Neff S, Raymond T, Kocer SS, Gavrilovskaya IN, Mackow ER. Pathogenic and nonpathogenic hantaviruses differentially regulate endothelial cell responses. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:13837–42. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Takala A, Lahdevirta J, Jansson SE, Vapalahti O, Orpana A, Karonen SL, Systemic inflammation in hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome correlates with hypotension and thrombocytopenia but not with renal injury. J Infect Dis. 2000;181:1964–70. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Wimer BM. Implications of the analogy between recombinant cytokine toxicities and manifestations of hantavirus infections. Cancer Biother Radiopharm. 1998;13:193–207. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Conlon PJ, Procop GW, Fowler V, Eloubeidi MA, Smith SR, Sexton DJ. Predictors of prognosis and risk of acute renal failure in patients with Rocky Mountain spotted fever. Am J Med. 1996;101:621–6. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Kulzer P, Schaefer RM, Heidbreder E, Heidland A. [Hantavirus infection with acute kidney failure]. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 1992;117:1429–33. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

Figures

Tables

Cite This ArticleTable of Contents – Volume 10, Number 8—August 2004

| EID Search Options |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Please use the form below to submit correspondence to the authors or contact them at the following address:

Franz Maximilian Rasche, Division of Nephrology, Department of Internal Medicine II, University Hospital Ulm, Robert-Koch-Strasse 8, D-89081 Ulm, Germany; fax: +49-731-500-24483

Top