Volume 14, Number 5—May 2008

Dispatch

Sandfly Fever Sicilian Virus, Algeria

Abstract

To determine whether sandfly fever Sicilian virus (SFSV) is present in Algeria, we tested sandflies for phlebovirus RNA. A sequence closely related to that of SFSV was detected in a Phlebotomus ariasi sandfly. Of 60 human serum samples, 3 contained immunoglobulin G against SFSV. These data suggest SFSV is present in Algeria.

Recent attention has been drawn to Toscana virus (family Bunyaviridae, genus Phlebovirus, species Sandfly fever Naples virus) in countries surrounding the Mediterranean because the virus causes meningitis during summer. Sandfly fever Sicilian virus (SFSV) is a distinct arthropod-borne phlebovirus transmitted by sandflies, specifically by Phlebotomus papatasi (1). It was discovered in Italy (Palerma, Sicilia), where it affected troops of the World War II Allied Army Forces after the Sicily landings in 1943. SFSV infection produces a febrile illness during the warm season; in contrast with Toscana virus infection, SFSV infection is not associated with neurologic manifestations.

Human cases of SFSV infection have been reported from Italy, Egypt, Pakistan, Iran, and Cyprus (1,2). Seroprevalence studies performed with human or vertebrate serum indicate that SFSV, or a closely related virus, is circulating in Jordan (3), Israel (4), Sudan (5), Tunisia (6), Pakistan (7), Egypt (8), Bangladesh (9), and Iran (10). The most comprehensive study, initiated by Tesh et al. (11), did not find neutralizing antibodies reactive to SFSV in human serum from the Algerian populations of Tamanrasset and Djanet. Therefore, at the outset of this study, no evidence or data suggested the presence of SFSV in Algeria.

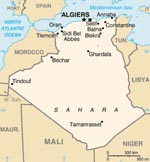

Over a 4-night period in July 2006, a total of 460 sandflies were trapped as described (12). Trapping was performed at Larbaa Nath Iraten (previously known as Fort National) in the Kabylian region of Algeria, near Tizi Ouzout (Figure 1). CDC Miniature Light Traps were adapted for sandfly capture by using an ultrafine mesh. Traps were hung 1–2 m above ground. They were placed during late afternoon in or near animal housing facilities (chickens, rabbits, goats, horses). Each morning, sandflies were collected, identified morphologically, and placed in 1.5-mL microfuge tubes. Captured sandflies belonged to 7 species: P. perniciosus (n = 364), P. longicuspis (n = 61), P. sergenti (n = 21), P. ariasi (n = 6), P. perfiliewi (n = 3), P. papatasi (n = 1), and Sergentomyia minuta (n = 1). They were organized into 24 pools, each containing up to 30 sandflies. Each pool was ground in RNA NOW chaotropic solution (Ozyme, Montigny le Bretonneux, France). RNA purification was performed according to the manufacturer’s protocol. A total of 10 μL of RNA suspension was used for reverse transcription with random hexanucleotide primers with the Taqman Reverse Transcription Reagents (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) in a final volume of 50 μL, according to the manufacturer’s recommended protocol. To test these specimens for Toscana virus RNA and phlebovirus RNA, we used 10 μL of cDNA in the previously described assays (12,13). Pool F tested positive with nested primers Phlebo2+/Phlebo2–. The PCR product was sequenced directly with primers used for PCR amplification. A 201-nt sequence (excluding primers) was obtained and submitted to the National Center for Biotechnology Information BLAST program, which retrieved a unique hit, consisting of Cyprus phlebovirus polymerase gene with a 92% identity score. Because Cyprus virus has been reported to be closely related to SFSV (2), we amplified and sequenced the homologous genome region of SFSV strain Sabin by using the primers described above. The same approach was applied to Arbia virus, a related phlebovirus isolated in Italy simultaneously with Toscana virus for comparative analysis. These 3 sequences were deposited in the GenBank database under accession nos. EU240880, EU266619, and EU266620. Laboratory contamination can be excluded because the sequence corresponding to SFSV-Algeria is divergent from its closest sequence (SFSV-Italy-Sabin) by 4%, which corresponds to 8 nt mutations; in addition, SFSV-Italy-Sabin has been manipulated after PCR amplification and sequencing of SFSV-Algeria to compare it genetically with the sequence obtained from Algerian sandflies.

Together with homologous sequences of selected phleboviruses, the 3 sequences determined in this study were used to perform genetic distance comparison and phylogenetic analysis. Nucleotide and amino acid distances are presented in the Table. Distance analysis unambiguously indicated that Algeria virus is a variant genotype of SFSV. The same conclusion applied to Cyprus phlebovirus. These 3 viruses exhibited amino acid and nucleotide distances of <9.3% and <7.5%, respectively. Phylogenetic analyses (Figure 2) indicated that Algeria formed a strong cluster (100% bootstrap support) with SFSV strain Sabin and the Cyprus phlebovirus. Therefore, we propose that they can be considered as 3 variant strains of the tentative species SFSV. Because sandfly material was stored in a chaotropic solution, virus isolation was not possible, which will necessitate field work with storage conditions suitable for virus isolation attempts.

Detection of SFSV RNA in sandflies led us to test human serum for SFSV antibodies. We tested 60 samples from healthy persons for SFSV immunoglobulin (Ig) G by indirect immunofluorescence assay as described (14) with minor modifications. Briefly, equal quantities of infected and uninfected Vero cells were mixed together and spotted onto 2-well glass slides through a 3-min cytospin-based centrifugation at 900 rpm. Samples were tested at a 1:20 dilution in phosphate-buffered saline. Three (5%) samples contained SFSV IgG but not Toscana virus IgG.

Together, molecular and serologic data constitute evidence that SFSV is present in Algeria. Genetic analysis of a partial region of the polymerase gene (L genome segment) indicated that the Algerian, Italian, and Cypriot strains of SFSV are closely related. Another study performed with M RNA sequences showed that Italian and Cypriot strains of SFSV are closely related as well (15).

To our knowledge, SFSV has been previously isolated in P. papatasi flies only. In this study, detection of SFSV RNA in 1 female P. ariasi sandfly must be interpreted with caution. In particular, this finding does not mean that P. ariasi is a vector of SFSV in the study region. The presence of SFSV RNA may result from mechanical transmission from a viremic vertebrate. Therefore, specific studies should be conducted to investigate vectors of SFSV in Algeria. Seroprevalence data demonstrate that SFSV or an SFSV-related virus can infect humans. Further studies are needed to determine whether the clinical picture is limited to self-resolving febrile illness, as previously reported in Italy.

Dr Izri is an entomologist who is interested in sandflies, specifically in their role as vectors of viral diseases of human and veterinary interest.

Acknowledgment

This work was partially supported by the RiVigene and VIZIER European Union FP6 Integrated Project.

References

- Karabatsos N. International catalogue of arboviruses including certain other viruses of vertebrates. San Antionio (TX): American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene; 1985.

- Papa A, Konstantinou G, Pavlidou V, Antoniadis A. Sandfly fever virus outbreak in Cyprus. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2006;12:192–4. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Batieha A, Saliba EK, Graham R, Mohareb E, Hijazi Y, Wijeyaratne P. Seroprevalence of West Nile, Rift Valley, and sandfly arboviruses in Hashimiah, Jordan. Emerg Infect Dis. 2000;6:358–62.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Cohen D, Zaide Y, Karasenty E, Schwarz M, LeDuc JW, Slepon R, Prevalence of antibodies to West Nile fever, sandfly fever Sicilian, and sandfly fever Naples viruses in healthy adults in Israel. Public Health Rev. 1999;27:217–30.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- McCarthy MC, Haberberger RL, Salib AW, Soliman BA, El-Tigani A, Khalid IO, Evaluation of arthropod-borne viruses and other infectious disease pathogens as the causes of febrile illnesses in the Khartoum Province of Sudan. J Med Virol. 1996;48:141–6. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Chastel CBB, Bach-Hamba D, Launay H, Le Lay G, Hellal H, Beaucornu JC. Infections à arbovirus en Tunisie : nouvelle enquête sérologique chez les petits mammifères sauvages. Bull Soc Pathol Exot. 1983;76:21–33.

- Darwish MA, Hoogstraal H, Roberts TJ, Ghazi R, Amer T. A sero-epidemiological sunvey for Bunyaviridae and certain other arboviruses in Pakistan. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1983;77:446–50. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Darwish MA, Feinsod FM, Scott RMN, Ksiazek TG, Botros BAM, Farrag IH, Arboviral causes of non-specific fever and myalgia in a fever hospital patient population in Cairo, Egypt. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1987;81:1001–3. DOIGoogle Scholar

- Gaidamovich SY, Baten MA, Klisenko GA, Melnikova YE. Serological studies on sandfly fevers in the Republic of Bangladesh. Acta Virol. 1984;28:325–8.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Saidi S, Tesh RB, Javadian E, Sahabi Z, Nadim A. Studies on the epidemiology of sandfly fever in Iran. II. The prevalence of human and animal infection with five phlebotomus fever virus serotypes in Isfahan province. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1977;26:288–93.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Tesh RB. Gajdamovic SJa, Rodhain F, Vesenjak-Hirjan J. Serological studies on the epidemiology of sandfly fever in the Old World. Bull World Health Organ. 1976;54:663–74.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Charrel RN, Izri A, Temmam S, Delaunay P, Toga I, Dumon H, Cocirculation of 2 genotypes of Toscana virus, southeastern France. Emerg Infect Dis. 2007;13:465–8.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Sanchez-Seco MP, Echevarria JM, Hernandez L, Estevez D, Navarro-Mari JM, Tenorio A. Detection and identification of Toscana and other phleboviruses by RT-nested-PCR assays with degenerated primers. J Med Virol. 2003;71:140–9. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Fulhorst CF, Monroe MC, Salas RA, Duno G, Utrera A, Ksiazek TG, Isolation, characterization and geographic distribution of Cano Delgadito virus, a newly discovered South American hantavirus (family Bunyaviridae). Virus Res. 1997;51:159–71. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Liu DY, Tesh RB, Travassos Da Rosa AP, Peters CJ, Yang Z, Guzman H, Phylogenetic relationships among members of the genus Phlebovirus (Bunyaviridae) based on partial M segment sequence analyses. J Gen Virol. 2003;84:465–73. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

Figures

Table

Cite This ArticleTable of Contents – Volume 14, Number 5—May 2008

| EID Search Options |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Please use the form below to submit correspondence to the authors or contact them at the following address:

Rémi N. Charrel, Université de la Mediterranée, Unite des Virus Emergents, 27 bd J Moulin Marseille 13005, France;

Top