Volume 15, Number 11—November 2009

Letter

Persistent Extended-Spectrum β-Lactamase Urinary Tract Infection

Cite This Article

Citation for Media

To the Editor: Uncomplicated urinary tract infections (UTIs) in otherwise healthy adults are usually treated empirically because the causative microbe is highly predictable: 80%–90% are caused by Escherichia coli. In addition, short courses of therapy (1 day or 3 days) are usually completed before laboratory results become available. In the past decade, reports of community-acquired, extended-spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL)–producing E. coli isolates have increased worldwide, but they are still uncommon in the United States (1), where reported cases are generally associated with hospitals. An early report of true community-acquired ESBL-producing E. coli infections in the United States was published in 2007 (2). We report a case of community-acquired lower UTI caused by ESBL-producing and multidrug resistant E. coli in an otherwise healthy college-aged woman who had no hospital exposure. Despite proper treatment, her infection persisted subclinically and symptoms recurred 2 months later.

The patient was an afebrile 24-year-old female college student who had visited her university health service, where she was recruited into a clinical trial investigating the effects of cranberry juice on UTIs. Inclusion in the study required that participants have UTI signs and symptoms, positive urine culture, and physician diagnosis. Participants provided self-collected vaginal, rectal, and midstream urine specimens at the time of enrollment and at 3- and 6-month follow-up or UTI recurrence. Study protocol was approved by the University of Michigan Institutional Review Board.

E. coli was isolated from all specimens collected from the patient at the time of enrollment; urinalysis confirmed pyuria (>100 leukocytes/high power field). Also at the time of enrollment, the patient reported no antimicrobial drug treatment during the previous 4 weeks, no history of hospitalization, no urethral catheterization, and no sexually transmitted infection (confirmed by medical record review). A 7-day regimen of nitrofurantoin was prescribed.

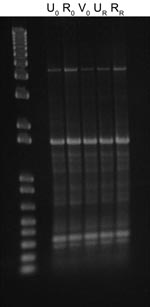

After 53 days, the patient returned to the health service with recurring UTI symptoms and was treated with a 3-day regimen of trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole; no urine specimen was submitted at that time. However, E. coli isolates were recovered from recurrence urine and rectal specimens collected within 48 hours according to the clinical trial protocol. All E. coli isolates collected at the time of enrollment (n = 3) and recurrence (n = 2) appeared morphologically and phenotypically identical (API Rapid 20E; bioMérieux, Durham, NC, USA). Genotyping using enterobacterial repetitive intergenic consensus (ERIC) PCR with an ERIC-2 primer showed a shared ERIC type, indicating identity (Figure). When tested for antimicrobial drug susceptibility (Vitek 2; bioMérieux), all 5 isolates were identified as ESBL-producers and were resistant to β-lactams: ampicillin, cefazolin, ceftriaxone (MIC >64 µg/mL), aztreonam, and piperacillin. After an ESBL confirmatory test, recommended by the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (3), showed positive results, the isolates were also considered resistant to ceftazidime (MIC 1–4 µg/mL) and cefepime. Disk diffusion indicated susceptibility to cefoxitin. The isolates were also resistant to fluoroquinolones, tetracycline, and trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole but susceptible to aminoglycosides, carbapenems, and nitrofurantoin. Isolates from the time of enrollment had intermediate susceptibility to amoxicillin–clavulanate (MIC 16 µg/mL), but isolates from the recurrence episode were resistant (MIC 32 µg/mL).

Although the patient’s initial UTI was treated adequately with nitrofurantoin, the infection recurred, implying that it remained in a reservoir, not uncommon for uncomplicated UTIs (4,5). Alternative antimicrobial drug treatment for outpatients with ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae is limited. Carbapenems remain the most effective drugs (6) but must be administered intravenously or intramuscularly (3). The reported efficacy of fosfomycin (7) suggests an option, but because agar dilution is the only recommended testing method, use of this drug in the United States is hindered. Use of antimicrobial drugs that concentrate in urine remains controversial as long as resistance is interpreted by MIC (blood-level resistance).

PCR detected β-lactamase resistance genes in all isolates, identifying them as ESBL positive when CTX-M consensus primer PCR was used but negative with TEM and SHV. Sequence analysis of the amplified gene showed that it encoded a CTX-M-15–like ESBL.

This isolate’s increasing resistance to a β-lactamase–inhibitor combination, amoxicillin–clavulanate, suggested the possibility of inducible AmpC β-lactamase production. A negative AmpC disk test (with Tris/EDTA, cefoxitin, and E. coli ATCC 25922) refuted a plasmid-mediated AmpC β-lactamase (6); the remaining possible resistance mechanisms were hyperproduction of β-lactamase or an inhibitor-resistant penicillinase.

For the patient reported here, the multiple drug–resistant strain persisted for at least 53 days despite appropriate treatment with antimicrobial drugs. Furthermore, medical record review found an additional UTI caused by E. coli 12 weeks later. Thus, because of the long duration of carriage of this highly resistant strain, potential for transmission to others is high.

The low number of previous reports of community-acquired ESBL in the United States does not necessarily suggest low community prevalence. Reports of ESBL-producer bacteremia in patients visiting emergency rooms suggests earlier and wider incidence (8). Returning to the practice of regularly culturing urine samples is difficult to justify; however, without ongoing surveillance to detect and control ESBL resistance, prevalence can only be expected to rise.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the invaluable contributions of Yong Cho, Marisol Lafontaine, Brady Miller, and Yuankai Zhou.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant R01 AT002086 (to C.B.-C.).

References

- Lewis JS II, Herrera M, Wickes B, Patterson JE, Jorgensen JH. First report of the emergence of CTX-M-type extended-spectrum beta-lactamases (ESBLs) as the predominant ESBL isolated in a U.S. health care system. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2007;51:4015–21. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Doi Y, Adams J, O'Keefe A, Quereshi Z, Ewan L, Paterson DL. Community-acquired extended-spectrum beta-lactamase producers, United States. Emerg Infect Dis. 2007;13:1121–3.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing: eighteenth informational supplement M100–S18. 2008;28:162–3, 174–5.

- Foxman B. Epidemiology of urinary tract infections: incidence, morbidity, and economic costs. Am J Med. 2002;113(Suppl 1A):5S–13S. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Hooton TM, Besser R, Foxman B, Fritsche TR, Nicolle LE. Acute uncomplicated cystitis in an era of increasing antibiotic resistance: a proposed approach to empiric therapy. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;39:75–80. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Moland ES, Kim S-Y, Hong SG, Thomson KS. Newer β-lactamases: clinical and laboratory implications, Part II. Clin Microbiol Newsl. 2008;30:79–85. DOIGoogle Scholar

- Rodríguez-Baño J, Alcalá JC, Cisneros JM, Grill F, Oliver A, Horcajada JP, Community infections caused by extended-spectrum β-lactamase–producing Escherichia coli. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:1897–902. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Reddy P, Malczynski M, Obias A, Reiner S, Jin N, Huang J, Screening for extended-spectrum β-lactamase–producing Enterobacteriaceae among high-risk patients and rates of subsequent bacteremia. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45:846–52. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

Figure

Cite This ArticleRelated Links

Table of Contents – Volume 15, Number 11—November 2009

| EID Search Options |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Please use the form below to submit correspondence to the authors or contact them at the following address:

Joan DeBusscher, University of Michigan, School of Public Health, Epidemiology, 1415 Washington Heights, Ann Arbor, MI 48109, USA

Top