Volume 15, Number 11—November 2009

Dispatch

Dengue Virus Serotype 4, Northeastern Peru, 2008

Figure 2

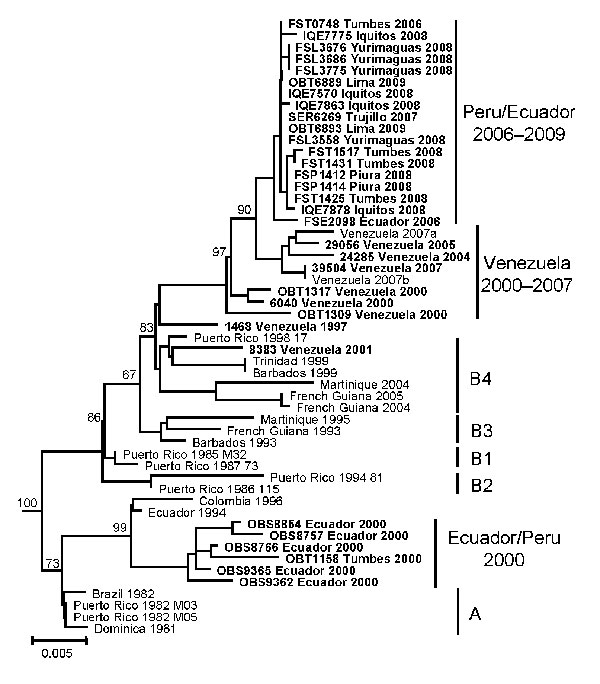

Figure 2. Phylogenetic analysis of the envelope gene of dengue virus serotype 4 (DENV–4) strains from Ecuador, Peru, and Venezuela. Similar topologies were observed from neighbor-joining (depicted), maximum likelihood, and maximum parsimony analyses, implemented in PAUP* v.4.0b10 (12). The general time reversible model of evolution was used for neighbor-joining and maximum-likelihood analyses. DENV-4 genotype I strains (not shown) were included as an outgroup. Bootstrap values (based on 1,000 replicates) >65 are shown at major nodes. Isolates first reported in this study are shown in boldface and with sample identification code. Some sequenced isolates from Peru and Venezuela that share high nucleotide identity (>99.7%) with depicted strains were omitted to reduce redundancy and improve clarity of the figure. Sequences were deposited in the GenBank database under the accession nos. GQ139572–GQ139577 (Ecuador), GQ139547–GQ139571 (Peru), and GQ139578–GQ139591 (Venezuela). Scale bar indicates number of nucleotide substitutions per site.

References

- Gubler DJ. Dengue/dengue haemorrhagic fever: history and current status. Novartis Found Symp. 2006;277:3–16; discussion 16–22, 71–3, 251–3.

- Pan American Health Organization (PAHO). Number of reported cases of dengue and dengue hemorrhagic fever (DHF), region of the Americas (by country and subregion) [cited 2008 Dec 20]. Available from http://www.paho.org/english/AD/DPC/CD/dengue-cases-2007.htm

- Guzman MG, Kouri G. Dengue and dengue hemorrhagic fever in the Americas: lessons and challenges. J Clin Virol. 2003;27:1–13. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Pinheiro F, Nelson M. Re-emergence of dengue and emergence of dengue haemorrhagic fever in the Americas. . Dengue Bull. 1997;21:1–6.

- Bennett SN, Holmes EC, Chirivella M, Rodriguez DM, Beltran M, Vorndam V, Selection-driven evolution of emergent dengue virus. Mol Biol Evol. 2003;20:1650–8. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Nogueira RM, de Araujo JM, Schatzmayr HG. Dengue viruses in Brazil, 1986-2006. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2007;22:358–63. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Wilson ME, Chen LH. Dengue in the Americas. Dengue Bull. 2002;26:44–61.

- Kochel T, Aguilar P, Felices V, Comach G, Cruz C, Alava A, Molecular epidemiology of dengue virus type 3 in northern South America: 2000–2005. Infect Genet Evol. 2008;8:682–8. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Foster JE, Bennett SN, Vaughan H, Vorndam V, McMillan WO, Carrington CV. Molecular evolution and phylogeny of dengue type 4 virus in the Caribbean. Virology. 2003;306:126–34. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Dussart P, Lavergne A, Lagathu G, Lacoste V, Martial J, Morvan J, Reemergence of dengue virus type 4, French Antilles and French Guiana, 2004–2005. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12:1748–51.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Klungthong C, Zhang C, Mammen MP Jr, Ubol S, Holmes EC. The molecular epidemiology of dengue virus serotype 4 in Bangkok, Thailand. Virology. 2004;329:168–79. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Swofford DL. PAUP*: phylogenetic analysis using parsimony (*and other methods). Version 4. Sunderland (MA): Sinauer Associates; 1998.

- Watts DM, Porter KR, Putvatana P, Vasquez B, Calampa C, Hayes CG, Failure of secondary infection with American genotype dengue 2 to cause dengue haemorrhagic fever. Lancet. 1999;354:1431–4. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Kochel TJ, Watts DM, Halstead SB, Hayes CG, Espinoza A, Felices V, Effect of dengue-1 antibodies on American dengue-2 viral infection and dengue haemorrhagic fever. Lancet. 2002;360:310–2. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Adams B, Holmes EC, Zhang C, Mammen MP Jr, Nimmannitya S, Kalayanarooj S, Cross-protective immunity can account for the alternating epidemic pattern of dengue virus serotypes circulating in Bangkok. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:14234–9. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar