Volume 16, Number 2—February 2010

Letter

Bronchial Casts and Pandemic (H1N1) 2009 Virus Infection

To the Editor: In the late 1990s, triple-reassortant influenza A viruses containing genes from avian, human, and swine influenza viruses emerged and became enzootic in swine herds in North America (1). The first 11 human cases of novel influenza A virus infection were reported to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC; Atlanta, GA, USA) from December 2005 through February 2009 (1). In response to those reports, surveillance for human infection with nonsubtypeable influenza A viruses was implemented.

In the spring of 2009, outbreaks of febrile respiratory infections caused by a novel influenza A virus (H1N1) were reported among persons in Mexico, the United States, and Canada (2). Patient specimens were sent to CDC for real-time reverse transcription–PCR (RT-PCR) testing, and from April 15 through May 5, 2009, a total of 642 infections with the virus, now called pandemic (H1N1) 2009 virus, were confirmed. Of those 642 patients, 60% were <18 years of age, indicating that children may be particularly susceptible to pandemic (H1N1) 2009 (2).

Children and adults with preexisting underlying respiratory conditions, such as asthma, are at increased risk for complications from infection with pandemic (H1N1) 2009 virus. One possible complication is plastic bronchitis, a rare respiratory illness characterized by formation of large gelatinous or rigid branching airway casts (3). Plastic bronchitis is a potentially fatal condition induced by bronchial obstruction from mucus accumulation resulting from infection, inflammation, or vascular stasis (4). We report a case of bronchial casts that caused atelectasis of the right lung of a child infected with influenza A pandemic (H1N1) 2009 virus.

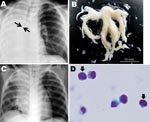

A 6-year-old boy with asthma and a 1-day history of fever and cough was referred to a hospital pediatrics department because of dyspnea. Clinical examination at hospital admission found respiratory distress, as shown by tachypnea (respiratory rate 66 breaths/min) and inspiratory retraction, deficient vesicular sounds over the right lung field, elevated blood levels of immunoglobulin E (1,770 IU/mL) and a reduced number of lymphocytes (483 cells/μL), and radiographic evidence of atelectasis of the right lung and hyperinflation of the left lung without air leakage (Figure, panel A). Pandemic (H1N1) 2009 virus infection was confirmed by real-time RT-PCR, as described (5), of an endotracheal aspirate. Real-time PCR ruled out Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Legionella pneumophila, Chlamydophila pneumoniae, S. pyogenes, respiratory syncytial viruses A and B, seasonal influenza viruses A and B, parainfluenza viruses 1–3, rhinovirus, enterovirus, human metapneumovirus, human bocavirus, and adenovirus (6). While the patient was breathing room air, his percutaneously monitored oxygen saturation was 86%; respiratory support by mechanical ventilation was then initiated. Mucus casts were extracted by intratracheal suction (Figure, panel B). The patient was treated with an inhaled bronchodilator, intravenous methylprednisolone (20–60 mg/day for 7 days), and antiviral (oseltamivir) and antimicrobial (ampicillin/sulbactam) drugs.

On hospital day 2, chest radiographs showed that atelectasis of the right lower lobe had partially resolved (Figure, panel C). A histologic examination of casts (May-Giemsa stain; Figure, panel D) indicated a mucoid substance containing a predominantly eosinophilic infiltrate (>90% of cells). The patient’s respiratory condition during 11 days of oxygen supplementation gradually improved, and he was discharged on hospital day 18.

Plastic bronchitis is related mainly to respiratory, cyanotic cardiac (post-Fontan), and hematologic (sickle cell anemia) diseases. A diagnosis of plastic bronchitis is determined on the basis of clinical findings (pointing to allergic and asthmatic, cardiac, or idiopathic etiologies) and pathologic findings (inflammatory vs. noninflammatory) on examination of casts (3). Inflammatory casts contain fibrin, eosinophils, and Charcot-Leyden crystals; noninflammatory casts contain mucin and exhibit vascular hydrostatic changes. The case presented here was the allergic-inflammatory type of plastic bronchitis.

Various treatments for plastic bronchitis have been described and vary from cast removal by expectoration or by bronchoscopy (7,8). Other interventions involve cast disruption by tissue plasminogen activator or urokinase and prevention of cast formation by use of mucolytic agents, steroids, or anticoagulants. However, evidence remains anecdotal because too few plastic bronchitis patients are available for clinical trials. Details of steroid dosage will need to be clarified for pandemic (H1N1) 2009 virus–infected children with respiratory distress from bronchitis and pneumonia.

In Iran during 1998–2001, avian influenza (H9N2) infection among broiler chickens resulted in 20%–60% mortality rates on affected farms (9). Macroscopic examination of specimens from infected chickens showed extensive hyperemia of the respiratory tract, followed by exudate and casts extending from the tracheal bifurcation to the secondary bronchi. Light microscopy indicated severe necrotizing tracheitis. Pandemic (H1N1) 2009 can produce similar airway cast formation in humans; severe respiratory distress reflects extensive obstruction of the respiratory system.

Healthcare providers should be aware of the possibility of bronchial casts when examining children with influenza (H1N1) infection accompanied by atelectasis. Steroids can be administered early in infection to avoid cast formation, and antiviral drug therapy and respiratory support can be used for influenza (H1N1)–infected children in whom airway casts have developed.

Acknowledgments

We thank Naoko Chiba and Akiko Ono for assistance with manuscript preparation.

This work was supported in part by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan (no. 21390306) to T.T.

References

- Shinde V, Bridges CB, Uyeki TM, Shu B, Balish A, Xu X, Triple-reassortant swine influenza A (H1) in humans in the United States, 2005–2009. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:2616–25. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Novel Swine-Origin Influenza A (H1N1) Virus Investigation Team, Dawood FS, Jain S, Finelli L, Shaw MW, Lindstrom S, et al. Emergence of a novel swine-origin influenza A (H1N1) virus in humans. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:2605–15. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Madsen P, Shah SA, Rubin BK. Plastic bronchitis: new insights and a classification scheme. Paediatr Respir Rev. 2005;6:292–300. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Kruger J, Shpringer C, Picard E, Kerem E. Thoracic air leakage in the presentation of cast bronchitis. Chest. 2009;136:615–7. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Hasegawa M, Hashimoto K, Morozumi M, Ubukata K, Takahashi T, Inamo Y. Spontaneous pneumomediastinum complicating pneumonia in children infected with 2009 pandemic influenza A(H1N1)v virus. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2010;16:195–9. Epub 2009 Oct 14. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Hamano-Hasegawa K, Morozumi M, Nakayama E, Chiba N, Murayama SY, Takayanagi R, Comprehensive detection of causative pathogens using real-time PCR to diagnose pediatric community-acquired pneumonia. J Infect Chemother. 2008;14:424–32. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Noizet O, Leclerc F, Leteurtre S, Brichet A, Pouessel G, Dorkenoo A, Plastic bronchitis mimicking foreign body aspiration that needs a specific diagnostic procedure. Intensive Care Med. 2003;29:329–31.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Nayar S, Parmar R, Kulkarni S, Cherian KM. Treatment of plastic bronchitis. Ann Thorac Surg. 2007;83:1884–6. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Nili H, Asasi K. Natural cases and an experimental study of H9N2 avian influenza in commercial broiler chickens of Iran. Avian Pathol. 2002;31:247–52.PubMedGoogle Scholar

Figure

Cite This ArticleRelated Links

Table of Contents – Volume 16, Number 2—February 2010

| EID Search Options |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Please use the form below to submit correspondence to the authors or contact them at the following address:

Addresses for correspondence: Yasuji Inamo, Department of General Pediatrics, Nihon University Nerima-Hikarigaoka Hospital, Nihon University School of Medicine, 2-11-1, Hikarigaoka, Nerima-ku, Tokyo, 179-0072, Japan; ; or Takashi Takahashi, Laboratory of Infectious Diseases, Graduate School of Infection Control Sciences, Kitasato University, 5-9-1 Shirokane, Minato-ku, Tokyo 108-8641, Japan

Top