Volume 18, Number 2—February 2012

Dispatch

Multiorgan Dysfunction Caused by Travel-associated African Trypanosomiasis

Abstract

We describe a case of multiorgan dysfunction secondary to Trypanosoma brucei rhodesiense infection acquired on safari in Zambia. This case was one of several recently reported to ProMED-mail in persons who had traveled to this region. Trypanosomiasis remains rare in travelers but should be considered in febrile patients who have returned from trypanosomiasis-endemic areas of Africa.

We describe a British safari tourist with multi-organ dysfunction and shock secondary to African trypanosomiasis. This case illustrates the complications associated with treatment of Trypanosoma brucei rhodesiense infection and highlights a recent increase in cases reported to ProMED (www.promedmail.org) of trypanosomiasis in travelers to Zambia.

A 49-year-old woman with a 5-day history of fever, malaise, headache, dizziness, abdominal discomfort, diarrhea, and vomiting sought treatment 1 day after returning to the United Kingdom from a 2-week safari in Zambia. During the safari, she spent 3 days in the South Luangwa National Park, 3 days in the Lower Zambezi National Park, and 6 days in Kafue National Park. Initial blood films examined at Furness General Hospital were negative for malaria parasites but positive for trypanosomes. Urgent transfer of the patient to the Tropical and Infectious Disease Unit in Liverpool, UK, was arranged.

Upon arrival, the patient was dehydrated and had jaundice and tachycardia, but she initially was normotensive. Examination revealed reduced breath sounds at the lung bases and a distended, nontender abdomen. There was a mild erythematous rash on the patient’s abdomen, but no chancres. Results of a neurologic examination were unremarkable.

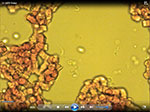

Repeat blood films confirmed numerous trypanosomes (Figure, Video), which, given the patient’s travel history, were considered likely to be T. b. rhodesiense. PCR results confirmed the trypanosomes positive for the T. b. rhodesiense–specific serum resistance–associated gene (1). Blood test results were as follows: urea 9.2 mmol/L, creatinine 146 μmol/L, leukocytes 3.7 × 109 cells/L, platelets 13 × 109/L, C-reactive protein 234 mg/L, alanine aminotransferase 179 U/L, bilirubin 38 μmol/L, and prothrombin time 13.5 s.

Despite fluid resuscitation, the patient became increasingly hypotensive over the next 12 hours, prompting transfer to the intensive care unit. A 100-mg test dose of suramin was well tolerated by the patient; however, the first full treatment dose was complicated by circulatory collapse and bronchoconstriction, which required administration of hydrocortisone and chlorphenamine and immediate discontinuation of the suramin infusion. Subsequent investigation showed that the suramin dose had been infused more rapidly than prescribed. Further doses administered as slow infusions were uncomplicated.

Hypotension persisted for 4 days but did not necessitate vasopressors. Results of a short synacthen test, electrocardiogram, and echocardiogram were normal.

After the patient received 2 treatment doses of suramin and analysis of repeat blood films confirmed that parasitemia had cleared, a lumbar puncture was performed. The cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) had 4 leukocytes/μL and normal levels of protein and glucose, and no trypanosomes were detected after double centrifugation.

The patient received a full course of suramin for early-stage disease, (regimen in Table 1), which resulted in full recovery. As follow-up care, the patient will receive repeat lumbar punctures every 3 months for 2 years to exclude occult invasion of the central nervous system (CNS). Thus far, 3 repeat lumbar punctures have shown no evidence of CNS invasion.

African trypanosomiasis is caused by the protozoan parasite T. brucei, which is transmitted by tsetse flies. Two subspecies are pathogenic in humans: T. b. gambiense in central and western Africa, and T. b. rhodesiense in eastern and southern Africa.

Disease progresses in 2 stages. In the first stage, parasites spread in the blood to the lymph nodes, liver, spleen, heart, endocrine system, and eyes (4). Untreated, they invade the CNS, which leads to second-stage or meningoencephalitic disease with characteristic sleep disturbances. Progression to the second stage may take months in T. b. gambiense infection but only weeks in T. b. rhodesiense infection.

Although trypanosomiasis is uncommon in travelers, it should be considered in the differential diagnosis of patients with fever who have returned from trypanosomiasis-endemic areas of Africa (5). Recent reports suggest an increase in cases emerging from Zambia, particularly from the South Luangwa Valley (Table 2) (6). Whether these cases reflect an increased risk for infection in that region or increasing tourism in a trypanosomiasis-endemic area is unclear. Infection in travelers is usually characterized by an acute febrile illness, sometimes associated with a macular evanescent rash or chancre (2,4). Laboratory tests often indicate anemia, thrombocytopenia, leukopenia, impaired renal function, electrolyte disturbances, coagulation abnormalities, and elevation in hepatic transaminase and C-reactive protein levels (2,7).

Conditions that should be considered in patients with persistent hypotension are adrenal insufficiency and cardiac dysfunction. The prevalence of adrenal insufficiency was 27% in a study of Ugandan patients with trypanosomiasis (8). Myocarditis, pericarditis, and congestive cardiac failure have been described and should be excluded by electrocardiogram and echocardiography (4).

The treatment for first-stage T. b. rhodesiense infection is intravenous suramin, given as 5 injections of 20 mg/kg each over 3–4 weeks (2,4). Early hypersensitivity reactions to suramin (i.e., nausea, circulatory collapse, and urticaria) are described in 0.1%–0.3% of patients; thus, an initial test dose is advocated (9).

Second-stage T. b. rhodesiense infection is treated with melarsoprol, a highly toxic arsenical which causes a severe reactive encephalopathy in ≈10% of patients, half of whom die as a result (10). This toxicity among patients emphasizes the importance of accurate staging, which is determined by CSF examination. According to World Health Organization guidelines, the presence of >5 leukocytes/μL and/or the presence of trypanosomes in the CSF indicates second-stage disease (11). Lumbar puncture should be deferred until clearance of blood parasitemia has been confirmed.

In view of our patient’s rapid onset of a high level of parasitemia, we investigated the possibility of a genetic susceptibility to trypanosomal infection. Human plasma contains a trypanosome lytic factor called apolipoprotein L-1 (APOL1) (12). This protein causes lysis of T. brucei subspecies other than rhodesiense and gambiense, both of which have acquired resistance to it (13). In 2006, Vanhollebeke et al. (14) described a patient infected with T. evansi, which is usually sensitive to APOL1. The patient’s serum lacked APOL1 due to mutations in the APOL1 gene, rendering him susceptible to a species regarded as nonpathogenic in humans. We sequenced the APOL1 gene of our patient, but no substantial variations suggesting enhanced susceptibility were detected.

In summary, trypanosomiasis remains rare in travelers, but possible infection should be considered in patients with fever who have returned from trypanosomiasis-endemic areas of Africa. Early reporting of trypanosomiasis cases to ProMED-mail allows timely recognition of emerging safari destinations that present an increased risk for infection to travelers. In patients with T. b. rhodesiense infection, multi-organ dysfunction may develop in early-stage disease. Treatment of such cases should be managed with critical care support, and it should be remembered that rapid infusion of suramin may precipitate circulatory collapse.

Dr Cottle is a specialist registrar in infectious diseases at the Tropical and Infectious Disease Unit in Liverpool, UK.

Acknowledgment

We acknowledge Anthony Macheta from Furness General Hospital.

References

- Welburn SC, Picozzi K, Fèvre EM, Coleman PG, Odiit M, Carrington M, Identification of human-infective trypanosomes in animal reservoir of sleeping sickness in Uganda by means of serum-resistance-associated (SRA) gene. Lancet. 2001;358:2017–9. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Brun R, Blum J, Chappuis F, Burri C. Human African trypanosomiasis. Lancet. 2010;375:148–59. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Abramowicz M. Drugs for parasitic infections. In: Abramowicz M, editor. The medical letter on drugs and therapeutics. New Rochelle (NY): The Medical Letter, Inc; 2000. p. 1–12.

- Kennedy PG. The continuing problem of human African trypanosomiasis (sleeping sickness). Ann Neurol. 2008;64:116–26. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Gautret P, Clerinx J, Caumes E, Simon F, Jensenius M, Loutan L, Imported human African trypanosomiasis in Europe, 2005–2009. Euro Surveill. 2009;14:pii:19327. PubMedGoogle Scholar

- ProMED-mail. Archive nos. 20100915.3338, 20101022.3833, and 20101111.4093 [cited 2011 Sep 22]. http://www.promedmail.org

- Sinha A, Grace C, Alston WK, Westenfeld F, Maguire JH. African trypanosomiasis in two travelers from the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 1999;29:840–4. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Reincke M, Arlt W, Heppner C, Petzke F, Chrousos GP, Allolio B. Neuroendocrine dysfunction in African trypanosomiasis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1998;840:809–21. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Burri C. Chemotherapy against human African trypanosomiasis: is there a road to success? Parasitology. 2010;137:1987–94. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Rodgers J. Human African trypanosomiasis, chemotherapy and CNS disease. J Neuroimmunol. 2009;211:16–22. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- World Health Organization. Control and surveillance of African trypanosomiasis. Report of a WHO expert committee. WHO Technical Report Series. 1998;881:I–VI, 1–114.

- Vanhamme L, Paturiaux-Hanocq F, Poelvoorde P, Nolan DP, Lins L, Van Den Abbeele J, Apolipoprotein L–I is the trypanosome lytic factor of human serum. Nature. 2003;422:83–7. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Pays E, Vanhollebeke B. Human innate immunity against African trypanosomes. Curr Opin Immunol. 2009;21:493–8. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Vanhollebeke B, Truc P, Poelvoorde P, Pays A, Joshi PP, Katti R, Human Trypanosoma evansi infection linked to a lack of apolipoprotein L–I. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:2752–6. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

Figures

Tables

Cite This Article1Current affiliation: Worthing Hospital, Worthing, UK.

Table of Contents – Volume 18, Number 2—February 2012

| EID Search Options |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Please use the form below to submit correspondence to the authors or contact them at the following address:

Lucy E. Cottle, Specialist Registrar in Infectious Diseases, Tropical and Infectious Disease Unit, Royal Liverpool University Hospital, Prescot St, Liverpool L7 8XP, UK

Top