Volume 18, Number 8—August 2012

Letter

Epidemic Clostridium difficile Ribotype 027 in Chile

Cite This Article

Citation for Media

To the Editor: The increased severity of Clostridium difficile infection is primarily attributed to the appearance of an epidemic strain characterized as PCR ribotype 027 (1). The only report that identified epidemic C. difficile ribotype 027 in an American country outside of North America comes from Costa Rica, raising the possibility that strains 027 might also be present in other countries of Latin America (2). Several studies between 2001 and 2009 have been conducted in South American countries to detect the incidence of C. difficile infection in hospitalized patients, but they did not identify which C. difficile strains were causing these infections (3).

During an epidemiologic screening of patients with C. difficile infection in a university hospital in Chile, we analyzed all stool samples of patients with suspected C. difficile infection during a 5-month period (June–November 2011). Two cases of C. difficile infection were associated with ribotype 027.

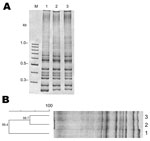

C. difficile was isolated from stool samples according to published protocols (4). Briefly, stool samples were spread onto taurocholate-cefoxitin-cycloserine fructose (Merck, Rahway, NJ, USA) agar plates and incubated for 96 hours at 37°C in a Bactron III-2 anaerobic workstation (SHEL LAB, Cornelius, OR, USA.). Plates were examined for the characteristic p-cresol odor unique to C. difficile culture (5). The aminopeptidase test (6) was also used to differentiate C. difficile strains. Suspected colonies were further analyzed by PCR to amplify tcdA, and tcdB genes (7). The presence of binary toxin gene (cdtB) and deletion in the negative regulator of the pathogenecity locus, tcdC, were determined by using Cepheid GeneXpert PCR (Cepheid, Sunnyvale, CA, USA). We used C. difficile ribotype 027 strain R20291 as a reference strain for comparative purposes. PCR ribotyping was performed as described (8). The specific ribotype 027 of each of the clinical isolates was determined by visual analysis and with the GelCompar II v6.5 software (Applied Maths, St-Martens-Latem, Belgium).

Case-patient 1 was a 60-year-old man with a history of coronary disease who required a coronary artery bypass graft because of 3-vessel coronary disease. Forty-eight hours after receiving 3 doses of cefazoline to prevent surgical wound infection, he exhibited severe and diffuse abdominal pain with frequent loose stools (8 bowel movements/day), fever (up to 39°C), and hemodynamic compromise, which required high doses of vasopressors. Stool samples were positive for C. difficile by ELISA, and the patient received intravenous metronidazole and oral vancomycin. However, because of the severity of the course of the disease, he underwent an urgent total colectomy with terminal ileostomy. The patient showed progressive improvement, and he was discharged 11 days after surgery. No relapse of C. difficile infection was reported in this patient in the next 5 months. Isolation of toxigenic culture and PCR demonstrated that the bacterial pathogen causing the diarrhea was C. difficile ribotype 027 (i.e., strain PUC51) (Figure).

Case-patient 2 was a 46-year-old man with a history of ischemic stroke with hemiparesis of the left side who had experienced a urinary tract infection that had been treated with ciprofloxacin 2 months earlier. Four weeks before admission, he had frequent loose stools with no fever and diffuse abdominal pain after meals. On admission, a computed tomographic scan and angiograph of the abdomen showed pancolitis with colonic wall thickening and scant ascites, suggestive of an inflammatory or infectious cause, without vascular compromise. However, ELISA of stool samples was negative for C. difficile toxin. Treatment with ceftriaxone reduced his symptoms, and he was discharged. Seven days after discharge, he had intense diffuse abdominal pain, with frequent loose stools and fever up to 38.9°C, and was again admitted to the hospital. A new computed tomographic scan of the abdomen showed no change; however, an ELISA of a new stool sample for C. difficile toxin was positive, and the patient was given oral vancomycin. No relapse of C. difficile infection was observed within 3 months of observation. Toxigenic culture from stool samples and PCR identified the C. difficile isolate as ribotype 027 (i.e., strain PUC47) (Figure).

Molecular typing analysis showed that both case-patients had a monoclonal infection caused by C. difficile ribotype 027. Both isolates had tcdA, tcdB, and cdtB and had a deletion in tcdC (data not shown).

In summary, the described severe cases of C. difficile infection in Chile were caused by epidemic C. difficile ribotype 027. One of these case-patients required urgent colectomy. These results demonstrate that epidemic C. difficile 027 strains are present in South America, highlighting the need for enhanced screening for this ribotype in other regions of the continent.

Acknowledgments

We thank Nigel Minton (University of Nottingham) for kindly providing C. difficile strain R20291.

This work was supported by grants from the Comisión Nacional de Investigación en Ciencia y Tecnologia (FONDECYT REGULAR 1100971) to M.A.-L. and S.B. and by grants from MECESUP UAB0802, Comisión Nacional de Investigación en Ciencia y Tecnologia (FONDECYT REGULAR 1110569) and from the Research Office of Universidad Andres Bello (DI-35-11/R) (to D.P.-S); and from the Medical Research Center, Facultad de Medicina of the Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, Resident Research Project (PG-20/11) to C. H.-R.

References

- McDonald LC, Killgore GE, Thompson A, Owens RC Jr, Kazakova SV, Sambol SP, An epidemic, toxin gene-variant strain of Clostridium difficile. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2433–41. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Quesada-Gómez C, Rodriguez C, Gamboa-Coronado Mdel M, Rodriguez-Cavallini E, Du T, Mulvey MR, Emergence of Clostridium difficile NAP1 in Latin America. J Clin Microbiol. 2010;48:669–70. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Balassiano IT, Yates EA, Domingues RM, Ferreira EO. Clostridium difficile: a problem of concern in developed countries and still a mystery in Latin America. J Med Microbiol. 2012;61:169–79. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Wilson KH, Kennedy MJ, Fekety FR. Use of sodium taurocholate to enhance spore recovery on a medium selective for Clostridium difficile. J Clin Microbiol. 1982;15:443–6.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Dawson LF, Donahue EH, Cartman ST, Barton RH, Bundy J, McNerney R, The analysis of para-cresol production and tolerance in Clostridium difficile 027 and 012 strains. BMC Microbiol. 2011;11:86. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Fedorko DP, Williams EC. Use of cycloserine-cefoxitin-fructose agar and L-proline-aminopeptidase (PRO Discs) in the rapid identification of Clostridium difficile. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:1258–9.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Rupnik M. Clostridium difficile toxinotyping. Methods Mol Biol. 2010;646:67–76. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Bidet P, Barbut F, Lalande V, Burghoffer B, Petit JC. Development of a new PCR-ribotyping method for Clostridium difficile based on ribosomal RNA gene sequencing. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1999;175:261–6. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

Figure

Cite This Article1These authors contributed equally to this article.

Related Links

Table of Contents – Volume 18, Number 8—August 2012

| EID Search Options |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Please use the form below to submit correspondence to the authors or contact them at the following address:

Daniel Paredes-Sabja, Laboratorio de Mecanismos de Patogénesis Bacteriana, Departamento de Ciencias Biológicas, Facultad de Ciencias Biológicas, Universidad Andrés Bello, Santiago, Chile

Top