Volume 19, Number 5—May 2013

Research

Full-Genome Deep Sequencing and Phylogenetic Analysis of Novel Human Betacoronavirus

Figure 2

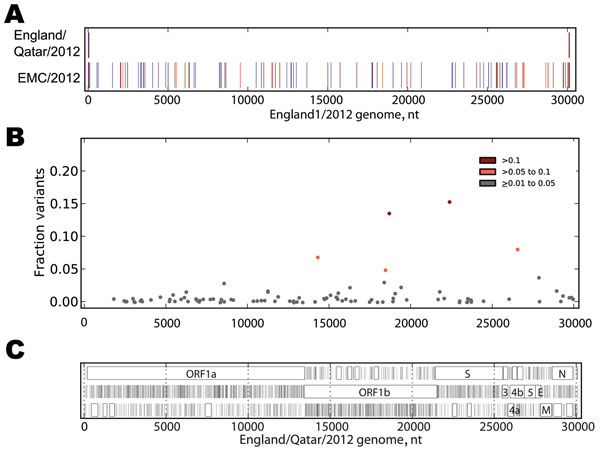

Figure 2. . . . A) Sequence differences among EMC/2012, England/Qatar/2012 and England1. The sequences of the 3 genomes were aligned, and differences between the sequence of England/Qatar/2012 and England1 (upper row) or EMC/2012 and England1 (lower row) were tabulated. The colored vertical ticks indicate nucleotide differences (change to A: red, change to T: dark red, change to G: indigo, change to C: medium blue, gap: gray). B) Non-consensus variants detected in the virus sample. The Illumina readset (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) for England/Qatar/2012 was mapped to the England/Qatar/2012 genome. Nucleotide positions showing nucleotides that differed from the consensus were tabulated. Colored dots indicate nucleotide positions with >1%–5% (gray), >5%–10% (orange), and >10% (red) nonconsensus variants. Positions with >5% variation and observed nucleotides are as follows: 14311: T, 92.07; G, 7.81; C, 0.12. 18460: C, 94.03; T, 5.97. 18692: G, 85.35; T, 14.65. 22385: G, 83.59; A, 16.41; C, 0.01. 26554: A, 90.85; G, 9.00; T, 0.15. C) Open reading frame (ORF) analysis of England/Qatar/2012. The positions of stop codons in each of the 3 forward ORFs are indicated by vertical black lines; the presence of ORFs of >75 aa are indicated by a closed box. ORF nomenclature is from Van Boheemen et al. (3).

References

- Haagmans BL, Andeweg AC, Osterhaus AD. The application of genomics to emerging zoonotic viral diseases. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000557. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Bolles M, Donaldson E, Baric R. SARS-CoV and emergent coronaviruses: viral determinants of interspecies transmission. Curr Opin Virol. 2011;1:624–34.

- van Boheemen S, de Graaf M, Lauber C, Bestebroer TM, Raj VS, Zaki AM, Genomic characterization of a newly discovered coronavirus associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome in humans. MBio. 2012;3:e00473-12.

- Bermingham A, Chand M, Brown C, Aarons E, Tong C, Langrish C, Severe respiratory illness caused by a novel coronavirus in a patient transferred to the United Kingdom from the Middle East, September 2012. Euro Surveill. 2012;17:20290 .PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Zaki AM, van Boheemen S, Bestebroer TM, Osterhaus AD, Fouchier RA. Isolation of a novel coronavirus from a man with pneumonia in Saudi Arabia. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1814–20. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Corman VM, Eckerle I, Bleicker T, Zaki A, Landt O, Eschbach-Bludau M, Detection of a novel human coronavirus by real-time reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction. Euro Surveill. 2012;17:20285 .PubMedGoogle Scholar

- World Health Organization. Novel coronavirus infection–update 21 February 2013 [cited 2013 Feb 21]. http://www.who.int/csr/don/2013_02_21/en/index.html

- Watson SJ, Welkers MR, Depledge DP, Coulter E, Breuer JM, de Jong MD, Viral population analysis and minority-variant detection using short read next-generation sequencing. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2013;368:20120205. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1754–60. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Zerbino DR, Birney E. Velvet: algorithms for de novo short read assembly using de Bruijn graphs. Genome Res. 2008;18:821–9. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Zerbino DR. Using the Velvet de novo assembler for short-read sequencing technologies. Curr Protoc Bioinformatics. 2010;Chapter 11:Unit 11.5.

- Gladman S, Seemann T. VelvetOptimiser [cited 2012 Oct 22]. http://www.vicbioinformatics.com/software.velvetoptimiser.shtml

- Edgar RC. MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:1792–7. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Tamura K, Peterson D, Peterson N, Stecher G, Nei M, Kumar S. MEGA5: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol Biol Evol. 2011;28:2731–9. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Guindon S, Dufayard JF, Lefort V, Anisimova M, Hordijk W, Gascuel O. New algorithms and methods to estimate maximum-likelihood phylogenies: assessing the performance of PhyML 3.0. Syst Biol. 2010;59:307–21. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Drummond AJ, Suchard MA, Xie D, Rambaut A. Bayesian phylogenetics with BEAUti and the BEAST 1.7. Mol Biol Evol. 2012;29:1969–73. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Health Protection Agency. Genetic sequence information for scientists about the novel coronavirus 2012 [2013 Feb 18]. http://www.hpa.org.uk/webw/HPAweb&HPAwebStandard/HPAweb_C/1317136246479

- Reusken CB, Lina PH, Pielaat A, de Vries A, Dam-Deisz C, Adema J, Circulation of group 2 coronaviruses in a bat species common to urban areas in Western Europe. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2010;10:785–91. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Falcón A, Vázquez-Morón S, Casas I, Aznar C, Ruiz G, Pozo F, Detection of alpha and betacoronaviruses in multiple Iberian bat species. Arch Virol. 2011;156:1883–90. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Zhao Z, Li H, Wu X, Zhong Y, Zhang K, Zhang YP, Moderate mutation rate in the SARS coronavirus genome and its implications. BMC Evol Biol. 2004;4:21. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Salemi M, Fitch WM, Ciccozzi M, Ruiz-Alvarez MJ, Rezza G, Lewis MJ. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus sequence characteristics and evolutionary rate estimate from maximum likelihood analysis. J Virol. 2004;78:1602–3. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Pyrc K, Dijkman R, Deng L, Jebbink MF, Ross HA, Berkhout B, Mosaic structure of human coronavirus NL63, one thousand years of evolution. J Mol Biol. 2006;364:964–73. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Lau SK, Lee P, Tsang AK, Yip CC, Tse H, Lee RA, Molecular epidemiology of human coronavirus OC43 reveals evolution of different genotypes over time and recent emergence of a novel genotype due to natural recombination. J Virol. 2011;85:11325–37. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Guan Y, Zheng BJ, He YQ, Liu XL, Zhuang ZX, Cheung CL, Isolation and characterization of viruses related to the SARS coronavirus from animals in southern China. Science. 2003;302:276–8. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Vijgen L, Keyaerts E, Moes E, Thoelen I, Wollants E, Lemey P, Complete genomic sequence of human coronavirus OC43: molecular clock analysis suggests a relatively recent zoonotic coronavirus transmission event. J Virol. 2005;79:1595–604. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Lau SK, Woo PC, Li KS, Huang Y, Wang M, Lam CS, Complete genome sequence of bat coronavirus HKU2 from Chinese horseshoe bats revealed a much smaller spike gene with a different evolutionary lineage from the rest of the genome. Virology. 2007;367:428–39. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Huynh J, Li S, Yount B, Smith A, Sturges L, Olsen JC, Evidence supporting a zoonotic origin of human coronavirus strain NL63. J Virol. 2012;86:12816–25. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Woo PC, Lau SK, Li KS, Poon RW, Wong BH, Tsoi HW, Molecular diversity of coronaviruses in bats. Virology. 2006;351:180–7. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Tang XC, Zhang JX, Zhang SY, Wang P, Fan XH, Li LF, Prevalence and genetic diversity of coronaviruses in bats from China. J Virol. 2006;80:7481–90. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Yip CW, Hon CC, Shi M, Lam TT, Chow KY, Zeng F, Phylogenetic perspectives on the epidemiology and origins of SARS and SARS-like coronaviruses. Infect Genet Evol. 2009;9:1185–96. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Müller MA, Raj VS, Muth D, Meyer B, Kallies S, Smits SL, Human coronavirus EMC does not require the SARS-coronavirus receptor and maintains broad replicative capability in mammalian cell lines. MBio. 2012;3:e00515-12.