Volume 20, Number 2—February 2014

Dispatch

Investigation of Inhalation Anthrax Case, United States

Cite This Article

Citation for Media

Abstract

Inhalation anthrax occurred in a man who vacationed in 4 US states where anthrax is enzootic. Despite an extensive multi-agency investigation, the specific source was not detected, and no additional related human or animal cases were found. Although rare, inhalation anthrax can occur naturally in the United States.

Anthrax is a naturally occurring disease, affecting herbivores that ingest bacterial spores when consuming contaminated vegetation or soil (1). Bacillus anthracis spores are highly resistant to weather extremes and can remain viable in soil and contaminated animal products, such as bones or hides, for many years (2,3). Heavy rains or flooding can bring spores to the surface or concentrate organic material and spores in low-lying areas. As surface water evaporates, spores may attach to growing vegetation or become concentrated in soil around roots (3,4).

Humans can become infected from exposure to infected animals or contaminated animal products (including meat, hides, and hair) or to contaminated dust associated with these products (1). Historically, inhalation anthrax was considered an occupational hazard for those working in wool and goat hair mills and tanneries (5). Recently, inhalation anthrax cases have resulted from exposure to African-style drums made of animal hides and from bioterrorist attacks (6,7). State or local health departments, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and the Federal Bureau of Investigation undertake epidemiologic and criminal investigations whenever a clinical isolate is confirmed as B. anthracis.

On August 5, 2011, a community hospital laboratory contacted the Minnesota Department of Health to submit for identification a Bacillus sp. blood isolate obtained from a patient hospitalized with pneumonia. The identification of B. anthracis was confirmed by nucleic acid amplification and gamma phage. CDC typed the isolate as GT59 using multiple-locus variable-number tandem repeat analysis specific for 8 loci (8). CDC also sequenced the strain and performed whole-genome single nucleotide polymorphism analysis. The isolate was related to strains with genotypes generally associated with imported animal products and most closely related to a strain obtained from a 1965 investigation of a case of cutaneous anthrax in a worker at a New Jersey gelatin factory, which used bone imported from India (9,10).

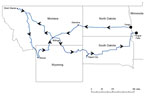

The patient, a 61-year-old Florida resident, had begun a 3-week trip with his wife on July 11, 2011. They drove through North Dakota, Montana, Wyoming, and South Dakota, where animal anthrax is sporadic or enzootic (Figure). While traveling, they walked in national parks, collected loose rocks, and purchased elk antlers. On July 29, they drove through herds of bison and burros, frequently stopping while animals surrounded their vehicle. The man was hospitalized on August 2, following onset of illness while he was en route to Minnesota. His condition was treated with antimicrobial drugs, according to published recommendations, supplemented with anthrax immune globulin, and he fully recovered (11). He and his wife were interviewed to identify potential sources of exposure. The Federal Bureau of Investigation found no concern for bioterrorism.

The couple had no contact with dead animals, but reported dusty conditions while driving through the herds. The patient had not traveled abroad during the past year or been exposed to tanneries, wool or goat hair mills, bone meal, African drums, or illicit drugs. He crafted metal and stone jewelry and knives with elk-antler handles in a home workshop. One month before illness onset, he had constructed fishing flies using hair from a healthy elk he hunted in Kentucky 8 months previously.

Because his wife may have experienced the same exposure, postexposure prophylaxis was provided, including a 60-day course of oral antimicrobial drugs and a 3-dose series of Anthrax Vaccine Adsorbed (Emergent Biosolutions, Lansing, MI, USA), under an investigational new drug protocol. Symptoms of anthrax did not develop; however, she was unable to provide blood for serologic testing before starting postexposure prophylaxis.

Environmental sampling of the entire trip route was not feasible because the travel route involved several thousand miles over 3 weeks, specific suspected exposure locations were lacking, and recovering B. anthracis from environmental samples (12), particularly soil (13), gives variable results and is inefficient. To identify an exposure source and focus the environmental investigation, investigators obtained targeted samples from the vehicle and personal items where spores were likely to be found. From the patient’s vehicle and contents, 47 environmental samples were collected, and 18 environmental samples were obtained from his home workshop and garage (Table), following procedures of the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health and the Environmental Protection Agency (14). All samples were processed and cultured by using CDC’s Laboratory Response Network culture and PCR methods at the Minnesota Department of Health and the Florida Department of Health. B. anthracis was not detected in any of the 65 samples.

Multiple agencies, including CDC, state public and animal health departments of Minnesota, North Dakota, Montana, Wyoming, South Dakota, and Florida, and other federal and state partners, conducted enhanced retrospective surveillance to identify other possible human or animal anthrax cases during June 1–August 31, 2011. Infection preventionists, medical examiners, and coroners were asked if they were aware of cases of unexplained death or fulminant illness potentially caused by anthrax. The US Department of Agriculture Veterinary Services and Wildlife Services/Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service, the Southeastern Cooperative Wildlife Disease Study, the US Geological Survey National Wildlife Health Center, the National Park Service, and state wildlife and veterinary agencies were asked to report unexplained animal die-offs and animal deaths consistent with anthrax. In addition, ≈450 Laboratory Response Network and 7 National Animal Health Laboratory Network laboratories in the participating states, the National Veterinary Services Laboratories, and other veterinary and wildlife laboratories were asked to review records for non-hemolytic Bacillus spp. isolates identified during the surveillance period.

No associated anthrax cases or isolates were found. A single bovine case was reported in Aurora County, South Dakota, in August 2011; however, the isolate was determined to be of an unrelated genotype (GT3). No other anthrax-associated die-offs in wildlife or domestic animals were identified, and no other suspected or confirmed human cases of anthrax were identified or reported during this period.

We did not find a specific exposure associated with anthrax infection for this case-patient and no other human or related animal cases. The clinical isolate genotype and sequence closely matched several previous environmental sample isolates from North America, however, no epidemiologic links were identified. The case-patient was exposed to airborne dust while traveling through areas where anthrax was enzootic; however, testing of vehicle air filters in which the dust was concentrated was negative for B. anthracis. Nonetheless, the patient may have been exposed through contact with an unidentified contaminated item. This investigation was limited by the poor sensitivity expected for soil sampling and lack of data to guide additional focused environmental sampling, precluding widespread random sample collection and testing along the route traveled.

It is unusual for inhalation anthrax case-patients to have no identified exposure source (5,9,15). Inhalation of spore-contaminated soil has been suggested as a possible source of infection for bison in anthrax outbreaks in Canada (16). A heavy equipment operator acquired inhalation anthrax during a bison outbreak in Canada, where he dragged carcasses to burial sites and was exposed to airborne dust during operations (2).

Chronic pulmonary disease or immunosuppression may increase a person’s susceptibility to inhalation anthrax (9,15). This case-patient had a decades-long history of chemical pneumonitis, and although he reported no respiratory difficulties, perhaps his risk was increased. He also had a history of mild diabetes; diabetes has been observed in other anthrax patients (9).

This report highlights the challenges of investigating cases of anthrax when no specific suspected source exists. Anthrax, either naturally-occurring or bioterrorism-related, is a major public health concern, and timely recognition is critical. Clinicians and public health professionals should be cognizant that naturally acquired anthrax can occur in the United States and take appropriate steps to rapidly diagnose and investigate such cases.

Ms. Griffith is the bioterrorism epidemiologist at the Minnesota Department of Health, Minneapolis. She is responsible for bioterrorism disease surveillance and biodetection program responses in the state.

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to the following persons for their help in this investigation: Neil Anderson, Bonnie Barnard, Joanne Bartkus, Anne Boyer, Beth Carlson, Richard Danila, Karin Ferlicka, Deborah Gibson, Bill Hartmann, Joseph Keenan, Susan Keller, Bill Layton, David Lonsway, William Marinelli, William Massello, Joseph Meyer, Elton Mosher, Jim Murphy, Conrad Quinn, Bruce Schwartz, Jonathan Sleeman, Tahnee Szymanski, Saba Tesfamariam, Jesse Vollmer, and Susanne Zanto.

Members of the Anthrax Investigation Team with affiliations: Civil Support Team, Minnesota National Guard, St. Paul, Minnesota, USA (Robb Mattila); Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Georgia, USA (Cari Beesley, William Bower, J. Bradford Bowzard, Gregory Burr, Leslie A. Dauphin, Mindy Glass Elrod, Chad Dowell, Jay Gee, Marta Guerra, Alex Hoffmaster, Chung Marston, Stephan Monroe, Meredith Morrow, Carol Rubin, David Sue, Rita Traxler, Tracee Treadwell, Katherine Hendricks Walters); Florida Department of Health, Bureau of Laboratories, Tampa, Florida, USA (P. Amuso); Florida Department of Health, Disease Control and Health Protection, St. Petersburg, Florida, USA (Pat Ryder, Ann Schmitz); Hennepin County Medical Center, Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA (Mark Sprenkle); Lake Region Healthcare, Fergus Falls, Minnesota, USA (Dawn Henkes); Minnesota Department of Health, St. Paul (Courtney Demontigny, Heather Fowler, Billie Juni, Nathan Kendrick, Christine Lees, Stefan Saravia, Joni Scheftel, Kirk Smith, Paula Snippes Vagnone); Montana Department of Public Health and Human Services, Helena, Montana, USA (Carrol Ballew); National Animal Health Laboratory Network, US Department of Agriculture, Fort Collins, Colorado, USA (Dale Nolte, Sarah Tomlinson); National Park Service, Office of Public Health, Albuquerque, New Mexico, USA (David Wong); National Park Service, Wildlife Health Branch, Fort Collins (Margaret Wild); National Veterinary Services Laboratories, Ames, Iowa, USA (Matthew Erdman, Barbara Martin); North Dakota Department of Health, Bismarck, North Dakota, USA (Tracy K. Miller, John R. Fischer, Jan Trythal); Northern Arizona University, Flagstaff, Arizona, USA (Paul Keim, Talima Ross Pearson) ; South Dakota Department of Health, Pierre, South Dakota, USA (Vicki Horan, Lon Kightlinger); University of Georgia, Athens, Georgia, USA (David Stallknecht); and Wyoming Department of Health, Cheyenne, Wyoming, USA (Tracy Murphy).

References

- Shadomy SV, Smith TL. Zoonosis update. Anthrax. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2008;233:63–72. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Pyper JF, Willoughby L. An anthrax outbreak affecting man and buffalo in the northwest territories. Med Serv J Can. 1964;20:531–40 .PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Dragon DC, Rennie RP. The ecology of anthrax spores: tough but not invincible. Can Vet J. 1995;36:295–301 .PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Hugh-Jones M, Blackburn J. The ecology of Bacillus anthracis. Mol Aspects Med. 2009;30:356–67. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Gastrointestinal anthrax after an animal-hide drumming event—New Hampshire and Massachusetts, 2009. [cited 2012 Jan 23]. MMWR Morbid Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;59:872–7. http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5928a3.htm

- Jernigan DB, Raghunathan PL, Bell BP, Brechner R, Bresnitz EA, Butler JC, Investigation of bioterrorism-related anthrax, United States, 2001: epidemiologic findings. Emerg Infect Dis. 2002;8:1019–28. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Keim P, Price LB, Klevytska AM, Smith KL, Schupp JM, Okinaka R, Multiple-locus variable-number tandem repeat analysis reveals genetic relationships with Bacillus anthracis. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:2928–36 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Bales ME, Dannenburg AL, Brachman PS, Kauffman AF, Klatsky PC, Ashford DA. Epidemiologic responses to anthrax outbreaks: a review of field investigations, 1950–2001. Emerg Infect Dis. 2002;8:1163–74 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Communicable Disease Center. Cutaneous anthrax—New Jersey. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1965;14:308.

- Sprenkle MD, Griffith J, Marinelli W, Boyer AE, Quinn CP, Pesik NT, Lethal factor and anti-protective antigen IgG levels associated with inhalation anthrax, Minnesota, USA. Emerg Infect Dis. 2014;20:310–4.

- Estill CF, Baron PA, Beard JK, Hein MJ, Larsen LD, Rose L, Recovery efficiency and limit of detection of aerosolized Bacillus anthracis Sterne from environmental surface samples. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2009;75:4297–306. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Kiel J, Walker WW, Andrews CJ, De Los Santos A, Adams RN, Bucholz MW, Pathogenic Ecology: where have all the pathogens gone? Anthrax: a classic case. In: Fountain AW, Gardner PJ, edidors. Proceedings of SPIE, vol. 7304. Chemical, Biological, Radiological, Nuclear, and Explosives (CBRNE Sensing X). 2009; 730402 .DOIGoogle Scholar

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Surface sampling procedures for Bacillus anthracis spores from smooth, non-porous surfaces. 2012 [cited 2013 Nov 15]. http://www.cdc.gov/niosh/topics/emres/surface-sampling-bacillus-anthracis.html.

- Brachman PS, Pagano JS, Albrink WS. Two cases of fatal inhalation anthrax, one associated with sarcoidosis. N Engl J Med. 1961;265:203–8. DOIGoogle Scholar

- Dragon DC, Elkin BT, Nishi JS, Ellsworth TR. A review of anthrax in Canada and implications for research on the disease in northern bison. J Appl Microbiol. 1999;87:208–13 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

Figure

Table

Cite This Article1Members of this Anthrax Investigation Team are listed at the end of the article.

Table of Contents – Volume 20, Number 2—February 2014

| EID Search Options |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Please use the form below to submit correspondence to the authors or contact them at the following address:

Jayne Griffith, Minnesota Department of Health, 625 Robert St North, PO Box 64975, St. Paul, MN 55164, USAJayne Griffith, Minnesota Department of Health, 625 Robert St North, PO Box 64975, St. Paul, MN 55164, USA

Top