Volume 20, Number 8—August 2014

Peer Reviewed Report Available Online Only

Preparedness for Threat of Chikungunya in the Pacific

Suggested citation for this article

Abstract

Chikungunya virus (CHIKV) caused significant outbreaks of illness during 2005–2007 in the Indian Ocean region. Chikungunya outbreaks have also occurred in the Pacific region, including in Papua New Guinea in 2012; New Caledonia in April 2013; and Yap State, Federated States of Micronesia, in August 2013. CHIKV is a threat in the Pacific, and the risk for further spread is high, given several similarities between the Pacific and Indian Ocean chikungunya outbreaks. Island health care systems have difficulties coping with high caseloads, which highlights the need for early multidisciplinary preparedness. The Pacific Public Health Surveillance Network has developed several strategies focusing on surveillance, case management, vector control, laboratory confirmation, and communication. The management of this CHIKV threat will likely have broad implications for global public health.

Chikungunya virus (CHIKV) is an alphavirus transmitted to humans by Aedes species mosquitoes, particularly Aedes aegypti and A. albopictus (1). It typically causes fever and severe and persistent joint pain (2). CHIKV was first recognized as a human pathogen in 1952 in Tanzania and, after several decades of little activity, has reemerged globally during the past decade (3). Chikungunya first appeared in the Pacific region in a small outbreak in New Caledonia in 2011 (1), but the virus is now a major threat in this reason. Outbreaks have been confirmed in Papua New Guinea (PNG) in June 2012 (4); New Caledonia in April 2013 (5); and Yap State, Federated States of Micronesia, in August 2013 (6). In this article, we give an overview of the virus, update the recent epidemiology of CHIKV, and assess the risk for CHIKV spread in the Pacific. We draw on lessons learned from the response efforts in the Indian Ocean, where the most devastating chikungunya epidemic so far caused havoc in a setting that is very similar to that of the Pacific Islands (7). We propose a series of public and clinical health measures to help Pacific Island countries and territories prepare for potential outbreaks of CHIKV infection.

Since 2000, chikungunya outbreaks have occurred in several regions of the world (3). Broadly speaking, the locations of these outbreaks appear to be moving in an easterly direction (3). Outbreaks occurred in the Democratic Republic of Congo in 2000 (8) and in Indonesia in 2001–2003 (9). In 2004, the virus appeared in Kenya; subsequently, a series of outbreaks occurred in the Indian Ocean during 2005–2007 (10). Affected locations included Seychelles (≈9,000 cases) (11), Comoros Islands (including 215,000 cases on Grande Comore) (12), Madagascar (12), Reunion Island (266,000 cases and 250 deaths) (12), Mauritius (≈6,000 cases) (11), and the Republic of the Maldives (13). During 2006–2007, outbreaks occurred in South and Southeast Asia (14). India reported 1.4 million cases (15), Sri Lanka 37,667 cases (15), and Malaysia 200 cases (15). Cases were also reported in Singapore in 2008 (16) and Thailand in 2008–2009 (17). The outbreaks in the Indian Ocean resulted in high attack rates, for example, 63% of the population in Grande Comore and 35% in Reunion Island (3,14,18).

Local chikungunya transmission had not been reported in the Pacific region until February 2011, when an autochthonous transmission of CHIKV was reported in New Caledonia (19). The first 2 cases were in persons who had recently returned from Indonesia; consistently, the virus was shown to belong to the Asian lineage. Only 33 cases were detected in total, and the outbreak was halted through aggressive case finding and vector control (1).

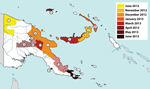

In June 2012, a chikungunya outbreak started in West Sepik Province of PNG (20). In December, the PNG National Department of Health reported on PacNet, which is the Pacific Public Health Surveillance Network (PPHSN) early warning system (21), that similar but unconfirmed cases had been detected in Madang and East New Britain Provinces. Since then, investigations have made it apparent that CHIKV spread east through PNG (Figure 1; Table 1) (4,22). In January 2013, confirmation of a case imported to Queensland, Australia, from PNG was reported (23). Since then, 10 more cases of chikungunya imported from PNG to Queensland have been reported (24).

At the end of April 2013, a chikungunya outbreak was confirmed in Noumea, the capital of New Caledonia (5). To date, 30 autochthonous cases have been confirmed, dating from early February through November 2013. The putative index case originated from the Indonesia, and the CHIKV was of the Asian lineage (data not shown).

In Yap State, an outbreak of chikungunya was reported in August 2013 (6). As of December 3, 2013, a total of 974 cases had been reported on Yap State and 128 cases on neighboring islands. The Yap State Department of Health Services posts weekly situational reports on PacNet to update the region. The path of introduction and the CHIKV genotype involved were not yet known at the time this article was prepared.

The CHIKV transmission cycle among humans can include Ae. aegypti or Ae. albopictus mosquitoes (25), both of which are widely spread in the Pacific region (Figure 2) (26). Some local Aedes mosquito species (e.g., Ae. polynesiensis) are also considered potential vectors. CHIKV has 3 genotypes, depending on its phylogenetic origins: West African, Asian, and East Central South African (ECSA) (27). The ECSA lineage may carry a point mutation in 1 gene of the E1 surface glycoprotein (E1:A226V), which greatly accelerates the replication cycle of the virus in the female Ae. albopictus mosquito, possibly from 5–7 days to 2–3 days (25). The ECSA virus strain was responsible for the largest documented epidemic of chikungunya in the Indian Ocean during 2005–2007 (28,29). CHIKV in PNG has been shown to be of the ECSA genotype and to carry this mutation (4). This genotype and mutation have also been confirmed in 4 of the recent cases imported to Queensland, Australia, from PNG (Forensic and Scientific Services, Department of Health, Queensland, Australia, pers. comm.). Furthermore, vector control measures in the Pacific may be hampered by pyrethroid resistance, which has already been described in Ae. aegypti mosquitoes in New Caledonia (1,30).

Overall, the incidence of emerging diseases is increasing worldwide (31), partly because of population mobility and airline travel; >2 billion passengers take commercial flights every year (32). As demonstrated by outbreaks in Italy in 2007 and in France in 2010, both of which originated in India, CHIKV can spread by airline routes (33,34). Linking disease and vector distribution with air travel data is considered an important method for risk assessment of vector-borne disease spread (32). Considering the development of the situation in PNG, New Caledonia, and Yap State, the risk that cases of CHIKV infection will be imported to other Pacific Islands and is substantial, depending on travel patterns and numbers of airline passengers between countries and territories where CHIKV is circulating. The risk would be especially high for countries and territories with large numbers of air travelers to and from countries and territories with ongoing epidemics. Direct flights from PNG go to Fiji, Solomon Islands, Vanuatu, Australia, the Philippines, Hong Kong, Malaysia, Singapore, and Japan. From New Caledonia, direct flights go to Japan, South Korea, Australia, Fiji, Wallis Island, French Polynesia, and New Zealand; from Yap State, flights go to Guam and Palau (Figure 3).

Documentation on previous CHIKV circulation in the Pacific is scarce, but studies from PNG and Indonesia from the 1970s indicate a seroprevalence of CHIKV in the population of up to 30% (35,36). These results should be interpreted with caution because of known antigenic cross-reactivity of arboviruses, including CHIKV; however, these finding indicate that CHIKV could have circulated in the region and that there may be immunity among some populations.

Thus, similar to the situation in the Indian Ocean during the devastating chikungunya outbreaks in 2005–2007 (7), the risk of introduction of the virus to the Pacific region, followed by severe consequences for the area, is high because of virus strain, vector competence, and population mobility. The human population also likely has little or no immunity, making them susceptible to transmission, but this needs further study. However, differences between the Indian Ocean and the Pacific, particularly in population density, may decrease the risk of spread.

Chikungunya had not previously been reported in Reunion Island, but during March 2005–April 2007, a total of 266,000 people—about one third of the population—were infected with CHIKV, and ≈250 people died (7,18). This outbreak resulted in a tremendous burden on the health system, peaking with >47,000 estimated cases in 1 week (7). The main risk factors for complications and death from CHIKV infection were age >65 years and preexisting diabetes and cardiovascular diseases (7,37). The economic costs of the epidemic were extreme, in large part because of absenteeism among both patients and caregivers, and the island economy had to be rescued by the central government of France under a specific crisis funding mechanism (38). Recurring and chronic joint pain affected one third of patients for 3 months to 1 year, and some case-patients have had these symptoms even longer (3), so that they are still affecting the health system and the socioeconomic well-being of the island’s population (38,39). Outbreaks of chikungunya and other diseases can also have a negative effect on tourism (40,41); the tourism industry is therefore a potentially important stakeholder to engage in prevention work.

The chikungunya outbreak in Reunion Island highlighted the importance of using a multidisciplinary approach to address medical and public health issues (42). Numerous teams in the arbovirus community rapidly focused their studies on CHIKV. One noticeable initiative was the creation of a CHIKV task force, comprising virologists, epidemiologists, entomologists, pathologists, immunologists, and clinicians working in Reunion Island (42,43).

Several lessons were learned from this experience. First and foremost were the limitations of island health care systems, which focus mainly on primary health care, to cope with so many cases of severe illness (44). The outbreak also emphasized the need for early preparedness to ensure the following: removal of potential vector-breeding sites; strengthening of vector control teams; efficient case management; adequate surveillance, case detection, and information and communication strategies; and the development of clear and consistent messages for behavior change campaigns (44,45).

To meet the need for early preparedness and consistent communication, the PPHSN has adopted an aggressive line of action in information dissemination. The PPHSN is a voluntary network of countries, territories, and organizations dedicated to the promotion of public health surveillance and appropriate response to the health emergencies for 22 Pacific Island countries and territories (Figure 2). The network was founded in 1996 under the auspices of the Secretariat of the Pacific Community and the World Health Organization (21).

The common surveillance system of the PPHSN is the Pacific Syndromic Surveillance System, which was introduced in October 2010 and implemented during the next 12 months in 20 of 22 Pacific Island countries and territories (46). This functional and timely regional infectious disease surveillance system tracks 4 core syndromes: acute fever and rash, diarrhea, influenza-like illness, and prolonged fever. Some countries also report the optional dengue-like illness. The frequency of syndromes is reported weekly to PPHSN partner World Health Organization in Suva, which prompts the countries and territories that there is an unexpected rise in a syndrome when the threshold of 90% of historically high reports is passed. The syndromes that would be expected to rise in frequency during dengue or chikungunya outbreaks are acute fever and rash, prolonged fever, and dengue-like illness (46,47). For confirmation testing of the causative agent of the outbreak, support is provided to Pacific Island countries and territories through the PPHSN laboratory referral network, LabNet (21).

In November 2012, a message was posted on PacNet relating that CHIKV infection occurred in PNG. In February 2013, a second communication was posted, relating to a case imported to Australia from PNG, including recommendations to the region (Table 2). The recommendations were derived through adapting international guidelines on preparedness for chikungunya outbreaks (48–53) to the Pacific setting, on the basis of syndromic surveillance as the common surveillance system (Table 2) (46,47). After the issuance of these recommendations, the outbreak of CHIKV infection in Yap State was declared in August 2013 and reported in a timely manner on PacNet and elsewhere (6). The Yap State EpiNet team, the multidisciplinary national action team of PPHSN (21), has been effectively reporting weekly on PacNet on their efforts to map and control the outbreak. Regional assistance has been provided in the form of technical discussions and expertise in epidemiology and entomology from PPHSN partners. Furthermore, the Pacific Outbreak Manual (http://www.spc.int/phs/PPHSN/Surveillance/Syndromic/Pacific_Outbreak_Manual-version1-2.pdf) is being updated to include specific response guidelines for CHIKV outbreaks. PacNet has previously been shown to be sensitive in terms of number of messages on regional epidemics or on potential regional threats (21) and has continuously been used to update the region of the development of all the chikungunya outbreaks in PNG, New Caledonia, and Yap State.

CHIKV has reached the Pacific, with current chikungunya outbreaks occurring in PNG, Yap State, and New Caledonia. The threat of further spread is high. A large chikungunya outbreak in the Pacific would have severe effects on health care systems and public health infrastructure and would potentially affect general functions of society, as did the epidemic in the Indian Ocean region (7). Learning from previous experience is of the utmost importance, and governments and leaders in the region need to act in a timely manner and ensure balanced communication campaigns to inform and update public health professionals of the situation. In a region where many countries and territories struggle to meet International Health Regulation requirements, the management of the current threat of CHIKV in the Pacific is likely to also have implications for other parts of the world (33).

Dr Roth is a medical epidemiologist specializing in clinical microbiology. He currently serves as team leader for surveillance and operational research for the Secretariat of the Pacific Community. His research interests focus on infectious disease epidemiology and monitoring of vaccine and other health intervention effects.

Acknowledgment

We thank the Direction des Affaires Sanitaires et Sociales in New Caledonia for sharing prompt updates of the chikungunya epidemic in New Caledonia and Boris Colas for designing the figures in the manuscript.

References

- Dupont-Rouzeyrol M, Caro V, Guillaumot L, Vazeille M, D’Ortenzio E, Thiberge JM, chikungunya virus and the mosquito vector Aedes aegypti in New Caledonia (South Pacific Region). Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2012;12:1036–41. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Staples JE, Breiman RF, Powers AM. Chikungunya fever: an epidemiological review of a re-emerging infectious disease. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49:942–8. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Burt FJ, Rolph MS, Rulli NE, Mahalingam S, Heise MT. Chikungunya: a re-emerging virus. Lancet. 2012;379:662–71. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Horwood PF, Reimer LJ, Dagina R, Susapu M, Bande G, Katusele M, Outbreak of chikungunya virus infection, Vanimo, Papua New Guinea. Emerg Infect Dis. 2013;19:1535–8. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Chikungunya (13): New Caledonia. ProMED. 2013 Apr 29 [cited 2013 Dec 3]. http://www.promedmail.org, archive no. 20130430.1681533.

- Chikungunya (47): Micronesia (Yap) alert. ProMED. 2013 Nov 11 [cited 2013 Dec 3]. http://www.promedmail.org, archive no. 20131114.2055640.

- Renault P, Solet JL, Sissoko D, Balleydier E, Larrieu S, Filleul L, A major epidemic of chikungunya virus infection on Reunion Island, France, 2005–2006. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2007;77:727–31.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Pastorino B, Muyembe-Tamfum JJ, Bessaud M, Tock F, Tolou H, Durand JP, Epidemic resurgence of chikungunya virus in Democratic Republic of the Congo: identification of a new central African strain. J Med Virol. 2004;74:277–82. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Porter KR, Tan R, Istary Y, Suharyono W, Sutaryo , Widjaja S, A serological study of chikungunya virus transmission in Yogyakarta, Indonesia: evidence for the first outbreak since 1982. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2004;35:408–15.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Chretien JP, Anyamba A, Bedno SA, Breiman RF, Sang R, Sergon K, Drought-associated chikungunya emergence along coastal East Africa. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2007;76:405–7.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Chikungunya and dengue, south-west Indian Ocean. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 2006;81:106–8.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Renault P, Balleydier E, D’Ortenzio E, Baville M, Filleul L. Epidemiology of chikungunya infection on Reunion Island, Mayotte, and neighboring countries. Med Mal Infect. 2012;42:93–101. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Chikungunya—Indian Ocean update (33): Maldives. ProMED. 2013 Dec 24 [cited 2012 Dec 3]. http://www.promedmail.org, archive no. 20061224.3598.

- Pulmanausahakul R, Roytrakul S, Auewarakul P, Smith DR. Chikungunya in Southeast Asia: understanding the emergence and finding solutions. Int J Infect Dis. 2011;15:e671–6. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Leo YS, Chow AL, Tan LK, Lye DC, Lin L, Ng LC. Chikungunya outbreak, Singapore, 2008. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009;15:836–7. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Pongsiri P, Auksornkitti V, Theamboonlers A, Luplertlop N, Rianthavorn P, Poovorawan Y. Entire genome characterization of Chikungunya virus from the 2008–2009 outbreaks in Thailand. Trop Biomed. 2010;27:167–76.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Jansen KA. The 2005–2007 chikungunya epidemic in reunion: ambiguous etiologies, memories, and meaning-making. Med Anthropol. 2013;32:174–89. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Alibert A, Pfannstiel A, Grangeon JP. Chikungunya outbreak in New Caledonia in 2011, Status report as at 22 August 2011. Inform’Action. 2011;34:3–9 [cited 2013 Dec 3] http://www.spc.int/phs/english/publications/informaction/IA34/Chikungunya_outbreak_New_Caledonia_status_report_22August2011.pdf

- Pavlin B. Chikungunya (10)—Papua New Guinea response. ProMED. 2013 Mar 24 [cited 2013 Dec 3. http://www.promedmail.org, archive no. 20130325.1602542.

- Souarès Y; Pacific Public Health Surveillance Network. Telehealth and outbreak prevention and control: the foundations and advances of the Pacific Public Health Surveillance Network. Pac Health Dialog. 2000;7:11–28.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Horwood P, Bande G, Dagina R, Guillaumot L, Aaskov J, Pavlin B. The threat of chikungunya in Oceania. Western Pac Surveill Response J. 2013;4:8–10. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Hide R. Chikungunya (12): Australia (Queensland) ex Papua New Guinea. 2013 Apr 27 [cited 2013 Dec 3]. http://www.promedmail.org, archive no. 20130427.1675486

- Queensland Health statewide weekly communicable diseases surveillance report, 25 November 2013 (for periods 18 November 2013–24 November 2013). 2013 Nov 25 [cited 2013 Dec 3]. http://www.health.qld.gov.au/ph/documents/cdb/weeklyrprt-131125.pdf

- Tsetsarkin KA, Vanlandingham DL, McGee CE, Higgs S. A single mutation in chikungunya virus affects vector specificity and epidemic potential. PLoS Pathog. 2007;3:e201. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Guillaumot L, Ofanoa R, Swillen L, Singh N, Bossin HC, Schaffner F. Distribution of Aedes albopictus (Diptera, Culicidae) in southwestern Pacific countries, with a first report from the Kingdom of Tonga. Parasit Vectors. 2012;5:247. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Powers AM, Logue CH. Changing patterns of chikungunya virus: re-emergence of a zoonotic arbovirus. J Gen Virol. 2007;88:2363–77. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- de Lamballerie X, Leroy E, Charrel RN, Ttsetsarkin K, Higgs S, Gould EA. Chikungunya virus adapts to tiger mosquito via evolutionary convergence: a sign of things to come? Virol J. 2008;5:33. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Schuffenecker I, Iteman I, Michault A, Murri S, Frangeul L, Vaney MC, Genome microevolution of chikungunya viruses causing the Indian Ocean outbreak. PLoS Med. 2006;3:e263. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Suivi de la resistance des moustiques aux insecticides. Noumea (New Caledonia): Institut Pasteur de Nouvelle-Caledonie; 2011.

- Jones KE, Patel NG, Levy MA, Storeygard A, Balk D, Gittleman JL, Global trends in emerging infectious diseases. Nature. 2008;451:990–3. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Tatem AJ, Huang Z, Das A, Qi Q, Roth J, Qiu Y. Air travel and vector-borne disease movement. Parasitology. 2012;139:1816–30. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Chretien JP, Linthicum KJ. Chikungunya in Europe: what’s next? Lancet. 2007;370:1805–6. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Grandadam M, Caro V, Plumet S, Thiberge JM, Souares Y, Failloux AB, Chikungunya virus, southeastern France. Emerg Infect Dis. 2011;17:910–3. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Kanamitsu M, Taniguchi K, Urasawa S, Ogata T, Wada Y, Wada Y, Geographic distribution of arbovirus antibodies in indigenous human populations in the Indo-Australian archipelago. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1979;28:351–63.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Tesh RB, Gajdusek DC, Garruto RM, Cross JH, Rosen L. The distribution and prevalence of group A arbovirus neutralizing antibodies among human populations in Southeast Asia and the Pacific islands. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1975;24:664–75.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Borgherini G, Poubeau P, Staikowsky F, Lory M, Le Moullec N, Becquart JP, Outbreak of chikungunya on Reunion Island: early clinical and laboratory features in 157 adult patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:1401–7. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Lagacherie P. Coverage of the chikungunya epidemic on Reunion Island in 2006 by the French healthcare system [in French]. Med Trop (Mars). 2012;72:97–8.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Gérardin P, Fianu A, Malvy D, Mussard C, Boussaid K, Rollot O, Perceived morbidity and community burden of chikungunya in La Reunion [in French]. Med Trop (Mars). 2012;72:76–82.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Flahault A, Aumont G, Boisson V, de Lamballerie X, Favier F, Fontenille D, Chikungunya, La Reunion and Mayotte, 2005–2006: an epidemic without a story? [in French]. Sante Publique. 2007;19(Suppl 3):S165–95.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Malavankar DV, Puwar TI, Murtola TM, Vasan SS. Quantifying the impact of chikungunya and dengue on tourism revenues. Ahmedabad (India): Indian Institute of Management; 2009.

- Flahault A, Aumont G, Boisson V, de Lamballerie X, Favier F, Fontenille D, An interdisciplinary approach to controlling chikungunya outbreaks on French islands in the south-west Indian ocean. Med Trop (Mars). 2012;72:66–71.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Schwartz O, Albert ML. Biology and pathogenesis of chikungunya virus. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2010;8:491–500. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Gaüzère BA, Gerardin P, Vandroux D, Aubry P. Chikungunya virus infection in the Indian Ocean: lessons learned and perspectives [in French]. Med Trop (Mars). 2012;72:6–12.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Bâville M, Dehecq JS, Reilhes O, Margueron T, Polycarpe D, Filleul L. New vector control measures implemented between 2005 and 2011 on Reunion Island: lessons learned from chikungunya epidemic [in French]. Med Trop (Mars). 2012;72:43–6.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Paterson BJ, Kool JL, Durrheim DN, Pavlin B. Sustaining surveillance: evaluating syndromic surveillance in the Pacific. Glob Public Health. 2012;7:682–94. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Kool JL, Paterson B, Pavlin BI, Durrheim D, Musto J, Kolbe A. Pacific-wide simplified syndromic surveillance for early warning of outbreaks. Glob Public Health. 2012;7:670–81. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Pan American Health Organization. Preparedness and response for chikungunya virus introduction in the Americas. Washington (DC): The Organization; 2011.

- Institut National de Prévention et d’Education pour la Santé. Dossier spécial chikungunya—point sur les connaissances et la conduite à tenir. Saint-Denis (France): Institut National de Prévention et d’Education pour la Santé (INPES); 2008 [cited 2013 May 10]. http://www.inpes.sante.fr/CFESBases/catalogue/pdf/1085.pdf

- Programme de surveillance, d’alerte et de gestion du risque d’émergence du virus chikungunya dans les départements français d’Amérique. Prefecture de Martinique. Ministère de la Santé et des Soidarités—République Française; 2007 [cited 2013 May 10]. http://opac.invs.sante.fr/doc_num.php?explnum_id=3518

- World Health Organization Regional Office for South-East Asia. Guidelines on clinical management of chikungunya fever. 2008 [cited 2013 May 10]. http://www.wpro.who.int/mvp/topics/ntd/Clinical_Mgnt_Chikungunya_WHO_SEARO.pdf

- Abeyewickreme W, Wickremasinghe AR, Karunatilake K, Sommerfeld J, Axel K. Community mobilization and household level waste management for dengue vector control in Gampaha district of Sri Lanka; an intervention study. Pathog Glob Health. 2012;106:479–87. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Arunachalam N, Tyagi BK, Samuel M, Krishnamoorthi R, Manavalan R, Tewari SC, Community-based control of Aedes aegypti by adoption of eco-health methods in Chennai City, India. Pathog Glob Health. 2012;106:488–96. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

Figures

Tables

Suggested citation for this article: Roth A, Hoy D, Horwood PF, Ropa B, Hancock T, Guillaumot L, et al. Preparedness for threat of chikungunya in the Pacific [online report]. Emerg Infect Dis [Internet]. 2014 Aug [date cited]. http://dx.doi.org/10.3201/eid2008.130696

Table of Contents – Volume 20, Number 8—August 2014

| EID Search Options |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Please use the form below to submit correspondence to the authors or contact them at the following address:

Adam Roth, Public Health Division, Secretariat of the Pacific Community, B.P.D5–98848 Noumea CEDEX, New Caledonia

Top