Volume 20, Number 9—September 2014

Letter

Urethritis Caused by Novel Neisseria meningitidis Serogroup W in Man Who Has Sex with Men, Japan

To the Editor: We report a case of urethritis caused by a novel multilocus sequence type (ST), 10651, of the ST11/electrophoretic type (ET)–37 complex Neisseria meningitidis serotype W. The patient was a man who has sex with men. We also report on the patient’s male partner, who was colonized with the same bacteria.

In March 2013, a 33-year-old Japanese man sought medical care at Shirakaba Clinic (Tokyo) after experiencing a urethral discharge for 4 days. The man was HIV positive (CD4 count 649 cells/μL) but was not receiving antiretroviral therapy. Physical examination showed a mucous urethral discharge. Gram staining of a sample revealed many gram-negative diplococci phagocytosed by polymorphonuclear leukocytes. Eleven days before seeking care, the patient had oral and anal intercourse with his male partner. A diagnosis of suspected urethritis caused by Neisseria gonorrhoeae was made, and a sample of the urethral discharge was sent for culture and testing (Strand Displacement Amplification) for N. gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis. The patient was intravenously administered a single dose of ceftriaxone (1 g) (intramuscular administration of ceftriaxone is not approved in Japan). He was also given a single dose of azithromycin (1g orally) for possible C. trachomatis urethritis (1).

Six days after receiving treatment, the patient showed improvement. Results of the Strand Displacement Amplification test were negative for N. gonorrhoeae and C. trachomatis. Eight days after the patient received treatment, the culture for the urethral discharge sample was shown to be positive for N. meningitidis. Urine culture was negative 20 days after treatment.

The 33-year-old male partner of the case-patient was originally from the United States and had been living in Japan for 4 years. Because of his history of sexual contact with the case-patient, he was advised to undergo a screening test for HIV and N. meningitidis. The man underwent a physical examination at our clinic 40 days after the case-patient received treatment; findings were unremarkable, and the result for HIV testing done 2 days earlier was negative. Throat and urine samples were obtained for culture, and the man was intravenously administered ceftriaxone (1 g). The urine sample culture was negative, but the throat sample culture was positive for N. meningitidis. The throat culture result was negative 10 days after the patient’s treatment.

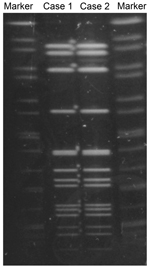

We performed cultures and tests to identify N. meningitidis, and we conducted multilocus sequence typing (MLST), serotyping, PorA typing, and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) as described elsewhere (2). Isolates from both men were identified as serotype W and PorA type P1.5, 2. MLST showed that the strains were ST10651 (genes analyzed: aroE:3, adk:4, fumC:3, gdh:8, pdhC:4, pgm:6, and abcZ:662). Although abcZ:662 was a novel allele, ST10651 belongs to the ST11/ET37 complex (3). We used PFGE with restriction enzyme NheI to compare the N. meningitidis strains from the case-patient and his partner; the isolates had the same PFGE pattern (Figure). Both isolates were confirmed to be a novel multilocus ST, 10651, of the ST11/ET37 complex; however, novel MLST types frequently occur. By using the E-test (Sysmex bioMérieux, Tokyo, Japan), we determined that the 2 isolates required the same minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) for the following antimicrobial drugs: penicillin (MIC 0.125 mg/L), ceftriaxone (MIC 0.004 mg/L), ciprofloxacin (MIC 0.004 mg/L), and azithromycin (MIC 0.25 mg/L) (4).

Urethritis caused by N. meningitidis infection in men who have sex with men (MSM) has been reported, as has an association between urethritis and oral sex (5,6). Most previously reported urogenital isolates of N. meningitidis have belonged to serogroups B (5,6), Y (5,6), and C (5). Among 115 cases of N. meningitidis infection in Japan during the last 9 years, 22 (19.1%) were caused by serogroup B and 18 (15.7%) were caused by serogroup Y; only 3 (2.6%) cases were caused by serotype W (7).

N. meningitidis ST11/ET37 complex is a hyperinvasive lineage. During the 1990s, the serogroup C ST11/ET37 complex was prominent in Europe and North America. However, in 2000, an outbreak of N. meningitidis serotype W infections occurred among Hajj pilgrims (8), and this serotype has now spread worldwide (3,8).

Chemoprophylaxis is indicated for persons who have close contact with someone with invasive meningococcal infection (9), but there is uncertainty regarding the treatment of asymptomatic persons who have contact with someone with N. meningitidis urethritis. To avoid a reinfection cycle between the men in this study, we treated the asymptomatic, N. meningitidis–colonized male partner.

Since the early 2000s, and especially since 2012, outbreaks of invasive serogroup C, ST11/ET37 complex meningococcal disease causing high rates of death have been reported among MSM in the United States and Europe (10). These outbreaks have raised policy questions concerning vaccination recommendations for HIV-infected persons and for the MSM population (10). In Japan, meningococcal vaccination has not been officially approved, and neither of the men in this study had been vaccinated against N. meningitidis.

A diagnosis of urethritis is often based on Gram staining or nucleic acid amplification tests (1). However, Gram staining cannot differentiate N. meningitidis from N. gonorrhoeae, and amplification tests only detect N. gonorrhoeae. This practice makes it difficult to diagnose and access the number of cases of N. meningitidis urethritis.

References

- Workowski KA, Berman S. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep. (Corrected in MMWR Recomm Rep. 2011 Jan 14;60:18 [Note: dosage error in article text]). 2010;59(RR-12):1–110.

- Takahashi H, Kuroki T, Watanabe Y, Tanaka H, Inouye H, Yamai S, Characterization of Neisseria meningitidis isolates collected from 1974 to 2003 in Japan by multilocus sequence typing. J Med Microbiol. 2004;53:657–62. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Neisseria sequence typing home page [cited 2014 May 3]. http://pubmlst.org/neisseria/

- Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing; twenty-third informational supplement. CLSI document M100–S23. Wayne (PA): The Institute; 2013.

- Janda WM, Morello JA, Lerner SA, Bohnhoff M. Characteristics of pathogenic Neisseria spp. isolated from homosexual men. J Clin Microbiol. 1983;17:85–91.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Oishi T, Ishikawa K, Tamura T, Tsukahara M, Goto M, Kawahata D, Precautions to prevent acute urethritis caused by Neisseria meningitidis in Japan [in Japanese]. Rinsho Byori. 2008;56:23–8.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Tanaka H, Kuroki T, Watanabe Y, Asai Y, Ootani K, Sugama K, Isolation of Neisseria meningitidis from healthy persons in Japan [in Japanese]. Kansenshogaku Zasshi. 2005;79:527–33.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- von Gottberg A, du Plessis M, Cohen C, Prentice E, Schrag S, de Gouveia L, Emergence of endemic serogroup W135 meningococcal disease associated with a high mortality rate in South Africa. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46:377–86. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Cohn AC, MacNeil JR, Clark TA, Ortega-Sanchez IR, Briere EZ, Meissner HC, Prevention and control of meningococcal disease: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep. 2013;62(RR-2):1–28.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Simon MS, Weiss D, Gulick RM. Invasive meningococcal disease in men who have sex with men. Ann Intern Med. 2013;159:300–1. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

Figure

Cite This ArticleRelated Links

Table of Contents – Volume 20, Number 9—September 2014

| EID Search Options |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Please use the form below to submit correspondence to the authors or contact them at the following address:

Kayoko Hayakawa, 1-21-1 Toyama, Shinjuku-ku, Tokyo, 162-8655, Japan

Top