Volume 21, Number 12—December 2015

Dispatch

Novel Waddlia Intracellular Bacterium in Artibeus intermedius Fruit Bats, Mexico

Cite This Article

Citation for Media

Abstract

An intracellular bacterium was isolated from fruit bats (Artibeus intermedius) in Cocoyoc, Mexico. The bacterium caused severe lesions in the lungs and spleens of bats and intracytoplasmic vacuoles in cell cultures. Sequence analyses showed it is related to Waddlia spp. (order Chlamydiales). We propose to call this bacterium Waddlia cocoyoc.

Because animals and humans have shared health risks from changing environments, it is logical to expand the perspective of public health beyond a single species. Bats are unique among mammals in their ability to fly and inhabit diverse ecologic niches. These characteristics together with their regularly large colonial populations highlight their potential as hosts of pathogens (1). Their role in disease epidemiology is supported by their susceptibility to different microorganisms such as bacteria, fungi, parasites, and viruses, as illustrated by the recent Ebola outbreak in West Africa (2). Previous and ongoing research is predominantly focused on viral agents, and the prevalence and effects of pathogenic bacteria in bats have been neglected (3).

Artibeus intermedius (the great fruit-eating bat) is a common frugivorous bat in the tropical Americas. Several pathogens of interest have been isolated from or detected in Artibeus spp. bats, including Histoplasma capsulatum, Trypanosoma cruzi, and eastern equine encephalitis, Mucambo, Jurona, Catu, Itaporanga, and Tacaiuma viruses (4–6), but their pathogenicity in bats is not known. In this study, a novel Chlamydia-like pathogenic bacterium was isolated from A. intermedius bats that were collected to characterize rabies virulence in a frugivorous bat species.

Adult A. intermedius bats (n = 38) were captured in the municipality of Cocoyoc in the state of Morelos, Mexico, in May 2012. Animals were kept in captivity by following the Guidelines of the American Society of Mammalogists for the Use of Wild Mammals in Research (7). Bats were observed for 2 months to ensure that existing infectious diseases did not develop. No animals had rabies antibodies detectable through rapid fluorescent focus inhibition test. Animals were inoculated intramuscularly with rabies virus (vampire bat variant 5020, 1×10 5.34Fluorescent Focus). After 5 days, an adult male exhibited emaciation, restlessness, and depression. On day 20, the animal could not fly and remained on the floor of the cage. Areas of pallor appeared on its wings (Technical Appendix Figure 1). The animal died on day 28. Testing showed negative results for rabies virus by direct immunofluorescence of brain tissue smears and by PCR of nervous tissue. Skin biopsies were taken from the wing lesions for histopathologic analyses and isolation.

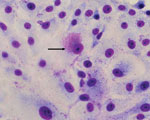

Vero cells inoculated with supernatant from homogenates of white spot lesion biopsies showed cytopathic effect (CPE) within 72 to 96 h postinoculation. CPE consisted of lytic plaque formation. Acidophilic inclusions visible by using Diff-Quick (VWR International, Briare, France) staining were detected within 48 and 72 h postinoculation (Figure 1). Similar inclusions could be seen after inoculation of BHK21 cells. The microorganism could not be cultured on blood or chocolate agar, aerobically or anaerobically, when incubated for up to 7 days.

Experimental inoculation was then established. Three bats that were seronegative for the isolated microorganism were inoculated intraperitoneally. The 3 animals were euthanized on days 5, 10, and 15. The bats euthanized on days 5 and 10 postinoculation showed signs of severe multifocal interstitial pneumonia (Technical Appendix Figure 2) and severe diffuse lymphoid hyperplasia in the spleen. On euthanization, the third bat showed signs of mild multifocal interstitial pneumonia and mild diffuse lymphoid hyperplasia in the spleen.

Two additional bats were inoculated subcutaneously; areas of pallor developed in the wing skin similar to those observed in the originally infected bat (Technical Appendix Figure 3). Mononuclear cells infected with bacteria were localized in skin (Technical Appendix Figure 4) and lung lesions of experimentally inoculated animals by immunofluorescence.

Histopathological findings in the areas of pallor through hematoxylin and eosin staining revealed the presence of mononuclear cell infiltrates in all subjects. Because of the resemblance of the wing lesions to those typically seen in white nose syndrome infection, which is caused by the fungus Pseudogymnoascus destructans, we applied periodic acid–Schiff staining to rule out fungal infection. No hyphae were identified.

Hyperimmune serum samples raised against the isolated bacteria neutralized the CPE of the bacteria up to a 1:719 dilution. Five (13%) of the 38 serum samples taken during captivity neutralized the CPE of the bacteria in dilutions ranging from 1:9 to 1:81. This result suggested circulation of this bacterium within the sampled population. All experimentally inoculated animals seroconverted. Serum samples from both animals that were inoculated subcutaneously neutralized the CPE of the bacteria up to a 1:27 dilution at day 28 postinoculation. Animals inoculated intraperitoneally and euthanized at 5, 10, and 15 days postinoculation neutralized CPE up to dilutions of 1:27, 1:27, and 1:81, respectively. No serum samples from the researchers who handled the bats showed seroneutralization activity.

DNA from skin biopsy samples and Vero and BHK 21 cells experimentally infected by using primers directed against domain I of the 23S gene of the family Waddliaceae yielded PCR products of the expected size (627 bp) (8). Vero cell culture was used to amplify the infection of the bacterial agent and DNA extracts were subjected to high throughput sequencing (SRA: PRJNA268154). Analysis of assembled contigs by using blastx (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi) showed that sequences close to Waddlia spp. were abundant (43%) and were only surpassed by 2 sequences of primate origin (Technical Appendix Figure 5). A neighbor-joining phylogenetic tree with 10,000 replicates was built with 16S sequences from assorted members of the order Chlamydiales and the cultured microorganism. The Chlamydiales have evolved from a single genus to a diverse order including new families such as Candidatus Parichlamydiaceae and Rhabdochlamiaceae (9). Phylogenetic analyses revealed that the newly identified Waddlia sp. segregates with known Waddlia spp. Although the new Waddlia sp. fell in the same taxonomic unit, it is found in its own branch (Figure 2). This finding was confirmed by a maximum-likelihood phylogeny with approximate likelihood ratio test (Technical Appendix Figure 6).

We report the isolation of a newly identified bacterial pathogen of A. intermedius bats and propose naming it Waddlia cocoyoc. The isolated bacterium was successfully grown in cell culture but not in inert bacterial growth media, suggesting dependence on host cells. Staining of inoculated cells revealed lysis and large intracytoplasmic vacuoles. Infected bats showed areas of pallor on the wings and had severe lesions in the lungs and the spleen. Histopathological analyses on the areas of pallor revealed mononuclear cell infiltrates in infected bats. Detection of the bacterium in lesion sites by immunofluorescence and PCR strongly suggests that it caused the observed pathogenesis. Phylogenetic analyses indicate that the pathogen is closely related to organisms in the family Waddliaceae.

Diversity in Waddliaceae increases as reports of new species surface. Waddlia spp. have been previously associated with Malaysian fruit bats (10). W. chondrophila has been isolated from aborted cattle fetuses in the United States (11), and was detected in a potoroo (Potorous spp.), a threatened marsupial native to Australia (12). Serologic evidence showed a substantive association between high titers of W. chondrophila antibodies and bovine abortion (13). In addition, W. chondrophila seroprevalence was found to be high in women who have had recurrent and sporadic miscarriages (14). W. chondrophila was also found in patients with community-acquired pneumonia (15). The host range and zoonotic potential of Waddlia spp. open multiple research avenues for this newly identified organism.

Dr. Pierlé has been a postdoctoral fellow at the Paul G. Allen School for Global Animal Health, Washington State University, and the Pasteur Institute, Paris, France. His research interests include genomics and transcriptomics of bacterial pathogens.

Acknowledgments

We thank António González Origel and Edgar A. Cuevas Domínguez from Wildlife Health, SEMARNAT (Ministry of Environment, Mexico) for his assistance in capturing and experimentation in wild animals.

This work was partially supported by IMSS (Mexico) grant FIS/IMSS/PROT/828.

References

- Kuzmin IV, Bozick B, Guagliardo SA, Kunkel R, Shak JR, Tong S, Bats, emerging infectious diseases, and the rabies paradigm revisited. Emerg Health Threats J. 2011;4:7159.http://dx.doi.org10.3402/ehtj.v4i0.7159PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Leroy EM, Kumulungui B, Pourrut X, Rouquet P, Hassanin A, Yaba P, Fruit bats as reservoirs of Ebola virus. Nature. 2005;438:575–6. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Mühldorfer K. Bats and bacterial pathogens: a review. Zoonoses Public Health. 2013;60:93–103. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Calisher CH, Kinney RM, de Souza Lopes O, Trent DW, Monath TP, Francy DB. Identification of a new Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus from Brazil. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1982;31:1260–72 .PubMedGoogle Scholar

- McMurray DN, Thomas ME, Greer DL, Tolentino NL. Humoral and cell-mediated immunity to Histoplasma capsulatum during experimental infection in neotropical bats (Artibeus lituratus). Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1978;27:815–21 .PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Reid JE, Jackson AC. Experimental rabies virus infection in Artibeus jamaicensis bats with CVS-24 variants. J Neurovirol. 2001;7:511–7. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Gannon WL, Sikes RS. Guidelines of the American Society of Mammalogists for the use of wild mammals in research. J Mammal. 2007;88:809–23. DOIGoogle Scholar

- Everett KD, Bush RM, Andersen AA. Emended description of the order Chlamydiales, proposal of Parachlamydiaceae fam. nov. and Simkaniaceae fam. nov., each containing one monotypic genus, revised taxonomy of the family Chlamydiaceae, including a new genus and five new species, and standards for the identification of organisms. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1999;49:415–40. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Stride MC, Polkinghorne A, Miller TL, Groff JM, Lapatra SE, Nowak BF. Molecular characterization of “Candidatus Parilichlamydia carangidicola,” a novel Chlamydia-like epitheliocystis agent in yellowtail kingfish, Seriola lalandi (Valenciennes), and the proposal of a new family, “Candidatus Parilichlamydiaceae” fam. nov. (order Chlamydiales). Appl Environ Microbiol. 2013;79:1590–7. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Chua PK, Corkill JE, Hooi PS, Cheng SC, Winstanley C, Hart CA. Isolation of Waddlia malaysiensis, a novel intracellular bacterium, from fruit bat (Eonycteris spelaea). Emerg Infect Dis. 2005;11:271–7. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Rurangirwa FR, Dilbeck PM, Crawford TB, McGuire TC, McElwain TF. Analysis of the 16S rRNA gene of micro-organism WSU 86–1044 from an aborted bovine foetus reveals that it is a member of the order Chlamydiales: proposal of Waddliaceae fam. nov., Waddlia chondrophila gen. nov., sp. nov. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1999;49:577–81. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Bodetti TJ, Viggers K, Warren K, Swan R, Conaghty S, Sims C, Wide range of Chlamydiales types detected in native Australian mammals. Vet Microbiol. 2003;96:177–87. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Dilbeck-Robertson P, McAllister MM, Bradway D, Evermann JF. Results of a new serologic test suggest an association of Waddlia chondrophila with bovine abortion. J Vet Diagn Invest. 2003;15:568–9. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Baud D, Thomas V, Arafa A, Regan L, Greub G. Waddlia chondrophila, a potential agent of human fetal death. Emerg Infect Dis. 2007;13:1239–43. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Haider S, Collingro A, Walochnik J, Wagner M, Horn M. Chlamydia-like bacteria in respiratory samples of community-acquired pneumonia patients. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2008;281:198–202 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

Figures

Cite This Article1Current affiliate: Institut Pasteur, Paris, France.

Table of Contents – Volume 21, Number 12—December 2015

| EID Search Options |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Please use the form below to submit correspondence to the authors or contact them at the following address:

Alvaro Aguilar Setién, Unidad de Investigación Médica en Inmunología, Coordinación de Investigación, Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social. Hospital de pediatría 3er piso, CMN Siglo XXI, Av Cuauhtémoc 330 Col Doctores, 06720 México DF, Mexico; .

Top