Volume 23, Number 6—June 2017

Dispatch

Domestic Pig Unlikely Reservoir for MERS-CoV

Figure 2

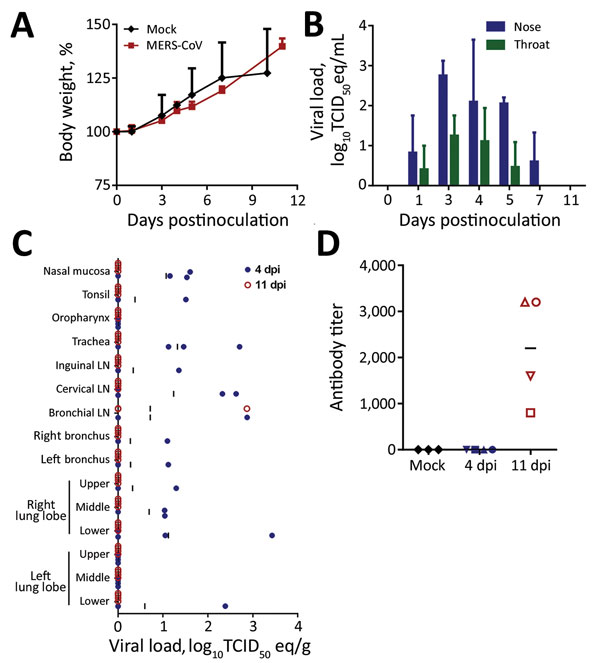

Figure 2. Propagation of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) in domestic pigs. We inoculated pigs intranasally and intratracheally with 106 tissue culture infectious dose 50 (TCID50) of MERS-CoV isolate hCoV-EMC/2012 or, for controls (mock-inoculated), with Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium. A) Mean bodyweight gain comparison between mock-inoculated and MERS-CoV–inoculated animals over time. Error bars indicate SDs. B) Mean viral loads shed from the nose and throat determined at the time points indicated by quantifying virus on nasal and throat swabs collected from MERS-CoV–inoculated animals using quantitative reverse transcription PCR (11); in each run, standard dilutions of a titered virus stock were run in parallel to calculate TCID50 equivalents. Error bars indicate SDs. C) Viral loads in tissues collected from MERS-CoV–inoculated animals on days 4 (closed blue circles) and 11 (open red circles) postinoculation. Viral loads were determined as in panel B. Vertical bars indicate means. D) Serum samples collected from pigs at the time of euthanasia (days 4 and 11 postinoculation) and tested for MERS-CoV antibodies by using an ELISA for MERS-CoV spike 1 protein. Antibody titers are plotted as the reciprocal of the last serum dilution positive by ELISA. Horizontal bars indicate means. LN, lymph node.

References

- World Health Organization. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV)–Saudi Arabia. Disease outbreak news. 2017 Mar 10 [cited 2017 Mar 15]. http://www.who.int/csr/don/10-march-2017-mers-saudi-arabia/en/

- Ng DL, Al Hosani F, Keating MK, Gerber SI, Jones TL, Metcalfe MG, et al. Clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and ultrastructural findings of a fatal case of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection in the United Arab Emirates, April 2014. Am J Pathol. 2016;186:652–8. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Munster VJ, de Wit E, Feldmann H. Pneumonia from human coronavirus in a macaque model. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:1560–2. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Baseler L, de Wit E, Feldmann H. A comparative review of animal models of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection. Vet Pathol. 2016;53:521–31. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Meurens F, Summerfield A, Nauwynck H, Saif L, Gerdts V. The pig: a model for human infectious diseases. Trends Microbiol. 2012;20:50–7. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Müller MA, Raj VS, Muth D, Meyer B, Kallies S, Smits SL, et al. Human coronavirus EMC does not require the SARS-coronavirus receptor and maintains broad replicative capability in mammalian cell lines. MBio. 2012;3:e00515-12. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- van Doremalen N, Munster VJ. Animal models of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection. Antiviral Res. 2015;122:28–38. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Lu G, Hu Y, Wang Q, Qi J, Gao F, Li Y, et al. Molecular basis of binding between novel human coronavirus MERS-CoV and its receptor CD26. Nature. 2013;500:227–31. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Wang N, Shi X, Jiang L, Zhang S, Wang D, Tong P, et al. Structure of MERS-CoV spike receptor-binding domain complexed with human receptor DPP4. Cell Res. 2013;23:986–93. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Corman VM, Eckerle I, Bleicker T, Zaki A, Landt O, Eschbach-Bludau M, et al. Detection of a novel human coronavirus by real-time reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction. Euro Surveill. 2012;17:20285.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- de Wit E, Rasmussen AL, Falzarano D, Bushmaker T, Feldmann F, Brining DL, et al. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) causes transient lower respiratory tract infection in rhesus macaques. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:16598–603. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Vergara-Alert J, van den Brand JM, Widagdo W, Muñoz M V, Raj S, Schipper D, et al. Livestock susceptibility to infection with Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus. Emerg Infect Dis. 2017;23:232–40. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar