Volume 24, Number 2—February 2018

Research

Spread of Meropenem-Resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae Serotype 15A-ST63 Clone in Japan, 2012–2014

Figure 1

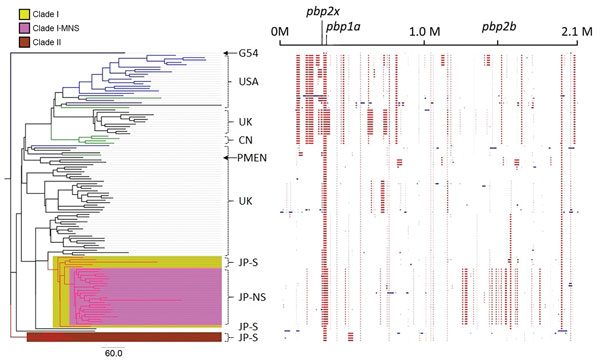

Figure 1. Phylogenic tree and predicted recombination sites created in Genealogies Unbiased By recomBinations In Nucleotide Sequences (28) by using all Japan and global serotype 15A-ST63 pneumococcal isolates. Branch colors in the tree indicate where the isolates were collected: red, Japan; black, United Kingdom; blue, United States; green, Canada. The column on the right of the tree indicates the main region from which the isolates were derived, meropenem susceptibility, and isolate names. The phylogenic tree was created by using Streptococcus pneumoniae G54 as an outgroup isolate. Clade I consists of only Japan serotype 15A-ST63 isolates; clade I-MNS consists of only Japan meropenem-nonsusceptible serotype 15A-ST63 isolates; clade II consists of the rest of the Japan meropenem-susceptible serotype 15A-ST63 isolates that are not included in clade I. The block chart on the right shows the predicted recombination sites in each isolate. Blue blocks are unique to a single isolate; red blocks are shared by multiple isolates. All isolates shaded in pink are meropenem nonsusceptible. Arrows indicate reference strains S. pneumoniae G54 and PMEN 15A-25. Scale bar indicates nucleotide substitutions per site; CN, Canada; G54, S. pneumoniae G54; M, million base pairs; JP-NS, Japan meropenem nonsusceptible; JP-S, Japan meropenem susceptible; PMEN, Pneumococcal Molecular Epidemiology Network; ST, sequence type; UK, United Kingdom; USA, United States.

References

- O’Brien KL, Wolfson LJ, Watt JP, Henkle E, Deloria-Knoll M, McCall N, et al.; Hib and Pneumococcal Global Burden of Disease Study Team. Burden of disease caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae in children younger than 5 years: global estimates. Lancet. 2009;374:893–902. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Geno KA, Gilbert GL, Song JY, Skovsted IC, Klugman KP, Jones C, et al. Pneumococcal capsules and their types: past, present, and future. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2015;28:871–99. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Waight PA, Andrews NJ, Ladhani NJ, Sheppard CL, Slack MP, Miller E. Effect of the 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine on invasive pneumococcal disease in England and Wales 4 years after its introduction: an observational cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2015;15:629. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Chiba N, Morozumi M, Shouji M, Wajima T, Iwata S, Ubukata K; Invasive Pneumococcal Diseases Surveillance Study Group. Changes in capsule and drug resistance of Pneumococci after introduction of PCV7, Japan, 2010-2013. Emerg Infect Dis. 2014;20:1132–9. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Metcalf BJ, Gertz RE Jr, Gladstone RA, Walker H, Sherwood LK, Jackson D, et al. Strain features and distributions in pneumococci from children with invasive disease before and after 13 valent conjugate vaccine implementation in the United States. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2015.p

- Song JY, Nahm MH, Moseley MA. Clinical implications of pneumococcal serotypes: invasive disease potential, clinical presentations, and antibiotic resistance. J Korean Med Sci. 2013;28:4–15. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Nakano S, Fujisawa T, Ito Y, Chang B, Suga S, Noguchi T, et al. Serotypes, antimicrobial susceptibility, and molecular epidemiology of invasive and non-invasive Streptococcus pneumoniae isolates in paediatric patients after the introduction of 13-valent conjugate vaccine in a nationwide surveillance study conducted in Japan in 2012-2014. Vaccine. 2016;34:67–76. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Duvvuri VR, Deng X, Teatero S, Memari N, Athey T, Fittipaldi N, et al. Population structure and drug resistance patterns of emerging non-PCV-13 Streptococcus pneumoniae serotypes 22F, 15A, and 8 isolated from adults in Ontario, Canada. Infect Genet Evol. 2016;42:1–8. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- van der Linden M, Perniciaro S, Imöhl M. Increase of serotypes 15A and 23B in IPD in Germany in the PCV13 vaccination era. BMC Infect Dis. 2015;15:207. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Sheppard C, Fry NK, Mushtaq S, Woodford N, Reynolds R, Janes R, et al. Rise of multidrug-resistant non-vaccine serotype 15A Streptococcus pneumoniae in the United Kingdom, 2001 to 2014. Euro Surveill. 2016;21:30423. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Chi HC, Hsieh YC, Tsai MH, Lee CH, Kuo KC, Huang CT, et al. Impact of pneumococcal conjugate vaccine in children on the serotypic epidemiology of adult invasive pneumococcal diseases in Taiwan. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2016;S1684-1182(16)30144-X.

- Cilveti R, Olmo M, Pérez-Jove J, Picazo JJ, Arimany JL, Mora E, et al.; HERMES Study Group. Epidemiology of otitis media with spontaneous perforation of the tympanic membrane in young children and association with bacterial nasopharyngeal carriage, recurrences and pneumococcal vaccination in Catalonia, Spain—The Prospective HERMES Study. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0170316. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Devine VT, Cleary DW, Jefferies JM, Anderson R, Morris DE, Tuck AC, et al. The rise and fall of pneumococcal serotypes carried in the PCV era. Vaccine. 2017;35:1293–8. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Kaur R, Casey JR, Pichichero ME. Emerging Streptococcus pneumoniae strains colonizing the nasopharynx in children after 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccination in comparison to the 7-valent era, 2006-2015. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2016;35:901–6. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Horácio AN, Silva-Costa C, Lopes JP, Ramirez M, Melo-Cristino J; Portuguese Group for the Study of Streptococcal Infections. Serotype 3 remains the leading cause of invasive pneumococcal disease in adults in Portugal (2012–2014) despite continued reductions in other 13-valent conjugate vaccine serotypes. Front Microbiol. 2016;7:1616. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Soysal A, Karabağ-Yılmaz E, Kepenekli E, Karaaslan A, Cagan E, Atıcı S, et al. The impact of a pneumococcal conjugate vaccination program on the nasopharyngeal carriage, serotype distribution and antimicrobial resistance of Streptococcus pneumoniae among healthy children in Turkey. Vaccine. 2016;34:3894–900. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Emory University. Pneumococcal Molecular Epidemiology Network (PMEN) [cited 2017 Nov 28]. http://web1.sph.emory.edu/PMEN/

- Hakenbeck R, Brückner R, Denapaite D, Maurer P. Molecular mechanisms of β-lactam resistance in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Future Microbiol. 2012;7:395–410. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Laible G, Spratt BG, Hakenbeck R. Interspecies recombinational events during the evolution of altered PBP 2x genes in penicillin-resistant clinical isolates of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Mol Microbiol. 1991;5:1993–2002. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Dowson CG, Hutchison A, Brannigan JA, George RC, Hansman D, Liñares J, et al. Horizontal transfer of penicillin-binding protein genes in penicillin-resistant clinical isolates of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989;86:8842–6. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Martin C, Sibold C, Hakenbeck R. Relatedness of penicillin-binding protein 1a genes from different clones of penicillin-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae isolated in South Africa and Spain. EMBO J. 1992;11:3831–6.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Tzouvelekis LS, Markogiannakis A, Psichogiou M, Tassios PT, Daikos GL. Carbapenemases in Klebsiella pneumoniae and other Enterobacteriaceae: an evolving crisis of global dimensions. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2012;25:682–707. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing; twenty-fifth informational supplement (M100–S25). Wayne (PA): The Institute; 2015.

- Croucher NJ, Finkelstein JA, Pelton SI, Parkhill J, Bentley SD, Lipsitch M, et al. Population genomic datasets describing the post-vaccine evolutionary epidemiology of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Sci Data. 2015;2:150058. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Kapatai G, Sheppard CL, Al-Shahib A, Litt DJ, Underwood AP, Harrison TG, et al. Whole genome sequencing of Streptococcus pneumoniae: development, evaluation and verification of targets for serogroup and serotype prediction using an automated pipeline. PeerJ. 2016;4:e2477. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Bankevich A, Nurk S, Antipov D, Gurevich AA, Dvorkin M, Kulikov AS, et al. SPAdes: a new genome assembly algorithm and its applications to single-cell sequencing. J Comput Biol. 2012;19:455–77. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990;215:403–10. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Croucher NJ, Page AJ, Connor TR, Delaney AJ, Keane JA, Bentley SD, et al. Rapid phylogenetic analysis of large samples of recombinant bacterial whole genome sequences using Gubbins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:e15. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Metcalf BJ, Chochua S, Gertz RE Jr, Li Z, Walker H, Tran T, et al.; Active Bacterial Core surveillance team. Using whole genome sequencing to identify resistance determinants and predict antimicrobial resistance phenotypes for year 2015 invasive pneumococcal disease isolates recovered in the United States. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2016;22:1002.e1–8. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Li Y, Metcalf BJ, Chochua S, Li Z, Gertz RE Jr, Walker H, et al. Penicillin-binding protein transpeptidase signatures for tracking and predicting β-lactam resistance levels in Streptococcus pneumoniae. MBio. 2016;7:e00756–16. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Minimum inhibitory concentrations predicted by the penicillin binding protein type [cited 2017 Nov 28]. https://www.cdc.gov/streplab/mic-tables.html

- Gertz RE Jr, Li Z, Pimenta FC, Jackson D, Juni BA, Lynfield R, et al.; Active Bacterial Core Surveillance Team. Increased penicillin nonsusceptibility of nonvaccine-serotype invasive pneumococci other than serotypes 19A and 6A in post-7-valent conjugate vaccine era. J Infect Dis. 2010;201:770–5. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Beall BW, Gertz RE, Hulkower RL, Whitney CG, Moore MR, Brueggemann AB. Shifting genetic structure of invasive serotype 19A pneumococci in the United States. J Infect Dis. 2011;203:1360–8. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Ardanuy C, de la Campa AG, García E, Fenoll A, Calatayud L, Cercenado E, et al. Spread of Streptococcus pneumoniae serotype 8-ST63 multidrug-resistant recombinant Clone, Spain. Emerg Infect Dis. 2014;20:1848–56. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Chochua S, Metcalf BJ, Li Z, Walker H, Tran T, McGee L, et al. Invasive serotype 35B pneumococci including an expanding serotype switch lineage, United States, 2015–2016. Emerg Infect Dis. 2017;23:922–30. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar