Volume 24, Number 6—June 2018

Dispatch

Mixed Leptospira Infections in a Diverse Reservoir Host Community, Madagascar, 2013–2015

Cite This Article

Citation for Media

Abstract

We identified mixed infections of pathogenic Leptospira in small mammals across a landscape-scale study area in Madagascar by using primers targeting different Leptospira spp. Using targeted primers increased prevalence estimates and evidence for transmission between endemic and invasive hosts. Future studies should assess rodentborne transmission of Leptospira to humans.

As a result of underreporting and lack of awareness, leptospirosis has been recognized as one of the world’s most neglected diseases (1). As is the case for other zoonotic pathogens, identifying key maintenance hosts and sources of human infection is essential for designing effective control strategies (2). However, leptospirosis epidemiology is complex; 10 pathogenic Leptospira species are phylogenetically delineated into 4 subgroups that differ in virulence and transmission (3), and multiple potential host species exist (4). In most studies, PCR protocols use primers targeting all pathogenic species, and the infecting Leptospira are identified on the basis of amplicon DNA sequence differences (5) or melt curve analyses (6). However, because of PCR primer biases or differences in infection intensities, such approaches probably underestimate mixed infections in areas with high Leptospira diversity.

Leptospirosis risk is high on islands in the western Indian Ocean; several Leptospira species on these islands are associated with disease (7). Studies in Madagascar have revealed acute cases of human leptospirosis and a seroprevalence of 3% (7–9). Studies of potential reservoirs in the region have revealed contrasting Leptospira–host associations. On Mayotte, an island neighboring Madagascar, 4 Leptospira species implicated in human disease (L. interrogans and L. kirschneri [taxonomic subgroup 1], L. borgpetersenii and L. mayottensis [taxonomic subgroup 2]) (7) have been detected in Rattus rattus rats (6), a highly successful invasive host introduced to the western Indian Ocean islands. However, Tenrec ecaudatus tenrecs, a mammal introduced from Madagascar, might also be a host of L. mayottensis (10). On Madagascar, only L. interrogans has been detected in invasive Rattus spp. rats (11), whereas L. borgpetersenii, L. mayottensis, and L. kirschneri have been detected in hosts endemic to Madagascar (5). In these studies, researchers did not attempt to identify mixed infections or sample invasive and endemic hosts from the same location, which would have been needed to fully assess Leptospira dynamics, spillover, and the role of hosts with widely different abundances and spatial distributions. Therefore, as part of a large landscape-scale study of Leptospira reservoirs in Madagascar, we developed quantitative PCRs (qPCRs) targeting individual Leptospira species and tested samples from small mammals to assess whether this approach changed our understanding of the reservoirs and spatial variation of risk.

We conducted trapping and sample collection under permits issued by the Madagascar Ministry of Environment and Forests (no. 154/13/ MEF/SG/DGF/DCB.SAP/SCB; no. 312/13/MEF/SG/DGF/DCB.SAP/SCB; no. 178/14/MEF/SG/DGF/DCB.SAP/SCB). We conducted this study in accordance with Institut Pasteur animal use guidelines (https://www.pasteur.fr/en/file/2626/download? token=YgOq4QW7); the study was approved by a committee of the Institut Pasteur de Madagascar.

During 2013–2015, we sampled small mammal hosts at 11 sites in Moramanga District, eastern Madagascar. Two sites were within an uninhabited humid forest, and the remaining sites included areas of human habitation and heterogeneous land use. We identified host species on the basis of phenotypic characteristics, external measurements, and craniodental measurements (when appropriate) (12). We euthanized and dissected animals and stored kidneys in 95% ethanol.

We extracted DNA from 0.04 g of kidney tissue with DNeasy Blood and Tissue Kit (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA, USA) using the manufacturer’s instructions and an elution volume of 100 µL. We detected Leptospira with a TaqMan qPCR assay targeting the 16S rRNA gene (13) using the StepOne Real-Time PCR System (Life Technologies, Waltham, MA, USA). Any sample with a cycle threshold <36 in 1 assay or <40 in 2 replicate assays was classified as Leptospira positive.

Initial genotyping of positive samples was achieved by amplification and sequencing of ≈300 bp of the lfb1 gene on an Eco-Illumina qPCR System (Illumina Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) (6). To characterize mixed infections, we designed forward primers targeting the lfb1 locus of 4 Leptospira species (L. interrogans 5′-CCTCTTACGCACAGATCRGTC-3′, L. borgpetersenii 5′-CCAACACTCCCTCCTCTATCAGC-3′, L. mayottensis 5′-CGCAGACTAGCAGCCCAACC-3′, and L. kirschneri 5′-GACCGCTTACGCACAGATCG-3′) and paired them with the standard lfb1 reverse primer using the same thermal profile. After sequencing, we retested samples with redesigned primers targeting Leptospira spp. not previously identified and sequenced those products (GenBank accession nos. MG759567–664). Each assay included a negative control (sterile water) for every 4 samples and a positive control. We purified PCR products using the QIAquick PCR Purification Kit (QIAGEN) and sent them to Eurofins Genomics GmbH (Ebersburg, Germany) for sequencing. We calculated prevalence and logit CIs using the binom package in R version 3.2.2 (https://cran.r-project.org/package=binom).

We captured 2,847 small mammals across 11 sites; 5 invasive species (R. rattus and R. norvegicus rats, Mus musculus mice, and Suncus murinus and S. etruscus shrews) accounted for 93% (2,653/2,847) of the captures. Of these, we captured R. rattus rats most frequently (n = 2,312) and at all sites, including forest sites. Although we found endemic hosts at all sites, 56% (107/190) were captured at forest sites. We tested 723 captured animals (43–102 animals/site) for Leptospira. We tested all endemic host samples and a subset of introduced host samples for each site. Overall prevalence of infection was 26%, ranging from 11% in Microgale spp. tenrecs to 48% in M. musculus mice (Table).

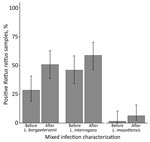

We genotyped 93 Leptospira-positive samples; the prevalence of mixed infections was 19% (95% CI 13%–29%). This value is still likely an underestimate, considering that cross-amplification of Leptospira species within the same taxonomic subgroup occurred. Mixed infections comprised L. interrogans and either L. borgpetersenii (n = 14) or L. mayottensis (n = 3); 1 animal was infected with all 3 species. All mixed infections were detected in rodents (order Rodentia): 78% (14/18) in R. rattus rats, 11% (2/18) in R. norvegicus rats, and the remaining 2 in endemic Nesomys rufus mice and Eliurus minor rats. After characterizing mixed infections, the proportion of R. rattus rats infected with L. borgpetersenii nearly doubled (Figure), and the number of L. mayottensis–infected R. rattus rats equaled the number of L. mayottensis–infected endemic hosts (n = 4). All of the L. mayottensis–infected R. rattus rats were captured at sites with human habitation; 75% (3/4) of L. mayottensis–infected endemic hosts were captured at forest sites. The L. interrogans lfb1 genotype most commonly identified was identical to the lfb1 sequence obtained from a human with a case of leptospirosis contracted in Madagascar (9).

We present definitive molecular evidence that small mammal hosts carry mixed infections of pathogenic Leptospira spp. The characterization of mixed infections and testing of sympatric endemic and invasive reservoir hosts has altered our understanding of leptospirosis epidemiology. Previously, only L. interrogans was detected in Rattus spp. rats in Madagascar (11). We show that, when mixed infections are characterized, the prevalence of L. borgpetersenii and L. interrogans in R. rattus rats is similar. Similar to findings from Mayotte (14), R. rattus rats are a potential source of human infection for 3 of the 4 Leptospira species present in Madagascar. Because of the high abundance and widespread distribution of these rats, they could act as a key reservoir for Leptospira, including for L. mayottensis, which might occur as spillover infections from endemic species.

The high prevalence of mixed Leptospira infections also provides a potential explanation for the genetic and serologic diversity of pathogenic Leptospira in the region (5,7), considering horizontal genetic transfer has been implicated in Leptospira evolution, including evolution of the locus responsible for serologic classification (rfb) (3). Further work is needed to better characterize the evolutionary and landscape-scale epidemiologic consequences of mixed infections. Moreover, the prevalence of infection and the identification of an lfb1 genotype in Rattus spp. rats identical to that in a human case (9) suggests that rodentborne transmission of Leptospira might be an underreported health problem in Madagascar. Studies on human exposure are urgently needed.

Dr. Moseley is a postdoctoral researcher in the Telfer group at the University of Aberdeen, Aberdeen, Scotland, UK. His research focuses primarily on understanding the transmission of zoonotic pathogens at the wildlife-livestock-human interface in the developing world.

Acknowledgments

We thank the staff of the Plague Central Laboratory, Institut Pasteur de Madagascar, for field and technical assistance, especially Fehivola Andriamiarimanana for DNA extractions and 16S qPCR assays; Toky Randriamoria for help with field work and identifying endemic species; and Mathieu Picardeau for supplying isolates used as positive controls in PCR experiments.

This work was supported by a Wellcome Trust Senior Fellowship (no. 095171 to S.T.), the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (grant no. BB/M010996/1), and the University of Aberdeen Environment and Food Security theme.

References

- Hartskeerl RA, Collares-Pereira M, Ellis WA. Emergence, control and re-emerging leptospirosis: dynamics of infection in the changing world. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2011;17:494–501. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Viana M, Mancy R, Biek R, Cleaveland S, Cross PC, Lloyd-Smith JO, et al. Assembling evidence for identifying reservoirs of infection. Trends Ecol Evol. 2014;29:270–9. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Picardeau M. Virulence of the zoonotic agent of leptospirosis: still terra incognita? Nat Rev Microbiol. 2017;15:297–307. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Bharti AR, Nally JE, Ricaldi JN, Matthias MA, Diaz MM, Lovett MA, et al.; Peru-United States Leptospirosis Consortium. Leptospirosis: a zoonotic disease of global importance. Lancet Infect Dis. 2003;3:757–71. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Dietrich M, Wilkinson DA, Soarimalala V, Goodman SM, Dellagi K, Tortosa P. Diversification of an emerging pathogen in a biodiversity hotspot: Leptospira in endemic small mammals of Madagascar. Mol Ecol. 2014;23:2783–96. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Merien F, Portnoi D, Bourhy P, Charavay F, Berlioz-Arthaud A, Baranton G. A rapid and quantitative method for the detection of Leptospira species in human leptospirosis. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2005;249:139–47. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Bourhy P, Collet L, Lernout T, Zinini F, Hartskeerl RA, van der Linden H, et al. Human leptospira isolates circulating in Mayotte (Indian Ocean) have unique serological and molecular features. J Clin Microbiol. 2012;50:307–11. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Ratsitorahina M, Rahelinirina S, Michault A, Rajerison M, Rajatonirina S, Richard V; 2011 Surveillance Workshop group. Has Madagascar lost its exceptional leptospirosis free-like status? PLoS One. 2015;10:e0122683. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Pagès F, Kuli B, Moiton M-PP, Goarant C, Jaffar-Bandjee M-CC. Leptospirosis after a stay in Madagascar. J Travel Med. 2015;22:136–9. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Lagadec E, Gomard Y, Le Minter G, Cordonin C, Cardinale E, Ramasindrazana B, et al. Identification of Tenrec ecaudatus, a wild mammal introduced to Mayotte Island, as a reservoir of the newly identified human pathogenic Leptospira mayottensis. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2016;10:e0004933. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Rahelinirina S, Léon A, Harstskeerl RA, Sertour N, Ahmed A, Raharimanana C, et al. First isolation and direct evidence for the existence of large small-mammal reservoirs of Leptospira sp. in Madagascar. PLoS One. 2010;5:e14111. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Soarimalala V, Goodman SM. Les petits mammifères de Madagascar. Antananarivo (Madagascar): Association Vahatra; 2011.

- Smythe LD, Smith IL, Smith GA, Dohnt MF, Symonds ML, Barnett LJ, et al. A quantitative PCR (TaqMan) assay for pathogenic Leptospira spp. BMC Infect Dis. 2002;2:13. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Desvars A, Naze F, Vourc’h G, Cardinale E, Picardeau M, Michault A, et al. Similarities in Leptospira serogroup and species distribution in animals and humans in the Indian ocean island of Mayotte. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2012;87:134–40. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

Figure

Table

Cite This ArticleOriginal Publication Date: May 07, 2018

Table of Contents – Volume 24, Number 6—June 2018

| EID Search Options |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Please use the form below to submit correspondence to the authors or contact them at the following address:

Mark Moseley, University of Aberdeen, School of Biological Sciences, Zoology Bldg, Tillydrone Ave, Aberdeen, Scotland AB24 2TZ, UK

Top