Volume 24, Number 8—August 2018

CME ACTIVITY - Research

Ancylostoma ceylanicum Hookworm in Myanmar Refugees, Thailand, 2012–2015

Figure 2

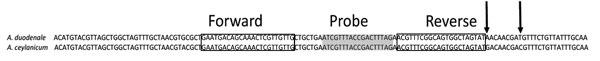

Figure 2. Partial internal transcribed spacer 2 (ITS2) sequences of Ancylostoma duodenale and A. ceylanicum hookworms. Boxes indicate the location of forward and reverse primer binding; gray shading indicates the location of probe binding. These regions of the A. duodenale and A. ceylanicum ITS2 are identical. The locations where the ITS2 sequences differ (arrows) fall outside of the primer and probe binding regions.

1These authors contributed equally to this article

Page created: July 11, 2018

Page updated: July 11, 2018

Page reviewed: July 11, 2018

The conclusions, findings, and opinions expressed by authors contributing to this journal do not necessarily reflect the official position of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, the Public Health Service, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, or the authors' affiliated institutions. Use of trade names is for identification only and does not imply endorsement by any of the groups named above.