Volume 24, Number 9—September 2018

Dispatch

Increasing Prevalence of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu stricto–Infected Blacklegged Ticks in Tennessee Valley, Tennessee, USA

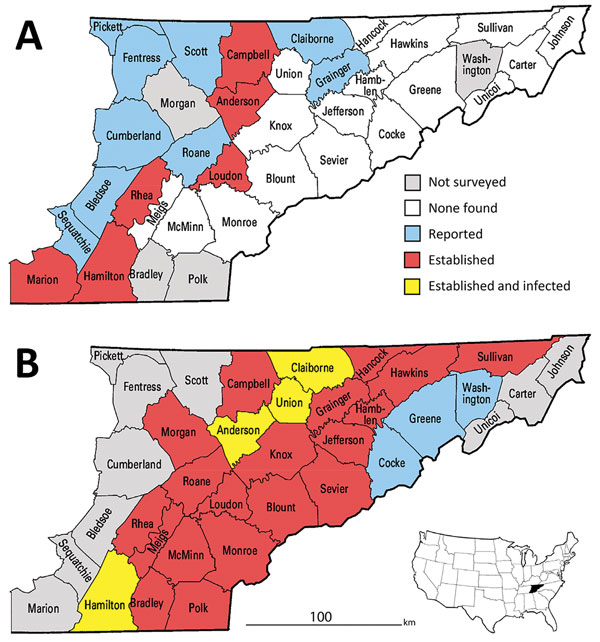

Figure 1

Figure 1. County-level distribution of Ixodes scapularis ticks and Borrelia burgdorferi–infected I. scapularis ticks in upper Tennessee Valley, USA, 2006 and 2017. A county was classified as having an established I. scapularis population if >6 I. scapularis adult ticks or ticks of 2 life stages were collected in that county. A county was classified as having I. scapularis ticks reported if 1–5 I. scapularis ticks of a single life stage were collected in that county. A county was classified as infected if I. scapularis ticks infected with B. burgdorferi were detected in that county. A) I. scapularis ticks in 2006 (2), determined by collecting ticks from hunter-harvested deer. B) I. scapularis ticks in 2017 determined by drag-cloth surveying during the peak of adult tick activity (late October–January).

References

- Mead PS. Epidemiology of Lyme disease. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2015;29:187–210. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Rosen ME, Hamer SA, Gerhardt RR, Jones CJ, Muller LI, Scott MC, et al. Borrelia burgdorferi not detected in widespread Ixodes scapularis (Acari: Ixodidae) collected from white-tailed deer in Tennessee. J Med Entomol. 2012;49:1473–80. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Eisen RJ, Eisen L, Beard CB. County-scale distribution of Ixodes scapularis and Ixodes pacificus (Acari: Ixodidae) in the continental United States. J Med Entomol. 2016;53:349–86. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Lantos PM, Nigrovic LE, Auwaerter PG, Fowler VG Jr, Ruffin F, Brinkerhoff RJ, et al. Geographic expansion of Lyme disease in the southeastern United States, 2000–2014. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2015;2:ofv143. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Herrin BH, Zajac AM, Little SE. Confirmation of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu stricto and Anaplasma phagocytophilum in Ixodes scapularis, Southwestern Virginia. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2014;14:821–3. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Keirans JE, Clifford CM. The genus Ixodes in the United States: a scanning electron microscope study and key to the adults. J Med Entomol Suppl. 1978;2:1–149.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Tsao JI, Wootton JT, Bunikis J, Luna MG, Fish D, Barbour AG. An ecological approach to preventing human infection: vaccinating wild mouse reservoirs intervenes in the Lyme disease cycle. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:18159–64. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Bunikis J, Garpmo U, Tsao J, Berglund J, Fish D, Barbour AG. Sequence typing reveals extensive strain diversity of the Lyme borreliosis agents Borrelia burgdorferi in North America and Borrelia afzelii in Europe. Microbiology. 2004;150:1741–55. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Stromdahl EY, Hickling GJ. Beyond Lyme: aetiology of tick-borne human diseases with emphasis on the south-eastern United States. Zoonoses Public Health. 2012;59(Suppl 2):48–64. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Arsnoe IM, Hickling GJ, Ginsberg HS, McElreath R, Tsao JI. Different populations of blacklegged tick nymphs exhibit differences in questing behavior that have implications for human lyme disease risk. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0127450. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Lockwood BH, Stasiak I, Pfaff MA, Cleveland CA, Yabsley MJ. Widespread distribution of ticks and selected tick-borne pathogens in Kentucky (USA). Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2018;9:738–41. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Apperson CS, Levine JF, Evans TL, Braswell A, Heller J. Relative utilization of reptiles and rodents as hosts by immature Ixodes scapularis (Acari: Ixodidae) in the coastal plain of North Carolina, USA. Exp Appl Acarol. 1993;17:719–31.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Levine JF, Apperson CS, Levin M, Kelly TR, Kakumanu ML, Ponnusamy L, et al. Stable transmission of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu stricto on the Outer Banks of North Carolina. Zoonoses Public Health. 2017;64:337–54. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Brinkerhoff RJ, Gilliam WF, Gaines D. Lyme disease, Virginia, USA, 2000-2011. Emerg Infect Dis. 2014;20:1661–8. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar