Volume 25, Number 11—November 2019

Dispatch

High Prevalence of Mansonella ozzardi Infection in the Amazon Region, Ecuador

Cite This Article

Citation for Media

Abstract

We reviewed Giemsa-stained thick blood smears, obtained through the national malaria surveillance program in the Amazon region of Ecuador, by light microscopy for Mansonella spp. microfilariae. Of 2,756 slides examined, 566 (20.5%) were positive. Nested PCR confirmed that the microfilariae were those of M. ozzardi nematodes, indicating that this parasite is endemic to this region.

Although mansonelliases is probably the most prevalent filarial infection worldwide, it is the least studied and is considered a neglected parasite infection (1,2). Human infection with members of the filarial nematode genus Mansonella, including M. ozzardi, M. perstans, and M. streptocerca nematodes, is common and widespread in the Western Hemisphere and Africa. M. ozzardi nematodes are found exclusively in the Western Hemisphere from southern Mexico to northwestern Argentina but have not been reported in Ecuador, Chile, Uruguay, and Paraguay (1,2). M. perstans infections are found mainly in sub-Saharan Africa, with sporadic cases in a few countries in South America, whereas M. streptocerca infections are found only in Africa (1–4).

Epidemiologic studies have reported that M. ozzardi nematodes are highly prevalent in the Amazon Basin (Brazil, Colombia, Peru, Bolivia, Venezuela, and Argentina) and on some Caribbean islands. In the general population, the prevalence rate of infection ranges from 0% to 46%; however, in some areas it is 92.3% (2).

Community health workers from the malaria control program in the Amazon region of Ecuador have reported that filaria-like nematodes are seen in thick blood smears, suggesting the presence of a Mansonella spp. in this area. Mansonella sp. nematodes are transmitted by dipteran flies. In particular, M. ozzardi nematodes are transmitted by biting midges of the genera Culicoides and by black flies from the genus Simulium (1). Both of these vectors are present in the Amazon region of Ecuador (Renato Leon, Universidad San Francisco de Quito, pers. comm., 2018 Dec 5).

Endemic areas for malaria and M. ozzardi infection often overlap; thus, microfilariae might be found on thick blood smears prepared for malaria diagnosis (2). Microfilariae of M. ozzardi can be easily distinguished morphologically from those of M. perstans by examination of the tail end: unlike M. ozzardi nematodes, the tails of M. perstans nematodes are blunt and have nuclei extending to the tail end (5). PCR-based amplification of species-specific target sequences results in increased diagnostic sensitivity and reliable differentiation between M. ozzardi nematodes and co-endemic filarial species, such as M. perstans and Onchocerca volvulus nematodes (6). Therefore, we conducted a retrospective study to document presence of human infections with Mansonella spp. nematodes in the Amazon region of Ecuador. The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Instituto Nacional de Investigación en Salud Pública (CEISH-INSPI-013).

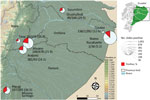

We conducted a study in 5 provinces (Sucumbíos, Orellana, Napo, Pastaza, and Morona Santiago) in the Amazon rainforest region of Ecuador for which malaria slides were available. The Amazon region of Ecuador covers ≈40% of the area of this country, extends from the eastern Andes to the lowlands of the Amazon basin, and borders Colombia and Peru.

The study population was composed of mestizos and Kichwa, Shuar, and Achuar indigenous groups. Community health workers collected blood samples by finger prick from 7:00

Thick and thin blood smears were stained with Giemsa and viewed by microscopy at 100× magnification under oil immersion for Plasmodium spp. parasites. We retrospectively screened all slides obtained during 2014–2015 for Mansonella spp. nematodes.

Although >5,000 stained blood smears were reviewed, only 2,756 slides could be read because of poor preservation. We examined thick and thin blood smears by using light microscopy and a 20× objective lens to detect microfilariae and a 40× objective lens for species identification. No epidemiologic data were available because we conducted a retrospective analysis.

Of 2,756 Giemsa-stained blood smears examined, we detected microfilariae of Mansonella spp. nematodes in 566 (20.5%). Microfilariae were unsheathed (average length 155 µm–212 µm) and had tapered, nonnucleated tails; anterior extremities ended in cephalic spaces. On the basis of these morphologic characteristics, we identified all filarial infections as M. ozzardi nematodes. Many microfilariae appeared damaged and partially destroyed. No microfilariae with the characteristics of M. perstans nematodes were observed. Infection rates between provinces ranged from 5.2% to 36.5%; infections were most prevalent in Morona Santiago, which borders Peru (Figure 1).

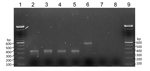

We then extracted DNA from all microscope slides positive for microfilariae. We scraped blood films off the slides into 70% ethanol. After microcentrifugation at 8,000 rpm for 2 min, we subjected supernatants to DNA extraction by using Chelex treatment (7), followed by proteinase K digestion. We performed a nested PCR according to the method of Tang et al. (6). This PCR amplifies the internal transcribed spacer region 1 of the rDNA gene of filarial species. The size of this region varies among O. volvulus, M. ozzardi, and M. perstans nematodes, and the PCR yields amplicons of different sizes for each species (6). Expected product sizes were 305 bp for M. ozzardi nematodes and 312 bp for M. perstans nematodes. PCR products after the second amplification were subjected to electrophoresis on 2% agarose gels (Figure 2).

We report a high frequency of autochthonous human mansonelliasis caused by M. ozzardi nematodes in the Amazon region of Ecuador. These parasites were identified by microscope identification of characteristic microfilariae and detection of species-specific DNA.

This study showed that human infections with M. ozzardi nematodes are highly prevalent throughout the Amazon region of Ecuador. High rates of circulating microfilariae are strongly suggestive of active local transmission, particularly because known vectors (biting midges of the genus Culicoides and black flies of the genus Simulium) are present in the surveyed region. Further entomologic studies are needed to identify specific Diptera species involved in local transmission of M. ozzardi nematodes in Ecuador.

Prevalence of M. ozzardi infection ranged from 5.2% to 36.5% in this study, similar to infection rates reported in bordering regions of Colombia and Peru, indicating that this region is probably a large focus of infection extending throughout several countries in the Amazon region (2). M. ozzardi infection rates were higher than those reported from Brazil, but considerably lower than those for the indigenous population of El Vaupés in Colombia, where the infection rate was 96% (8). However, in estimating prevalence by using stored, partially degraded blood smears and light microscopy, we might have underestimated the true prevalence. Use of FTA cards (Whatman, https://www.sigmaaldrich.com) has been demonstrated to be more sensitive for detection of M. ozzardi nematodes (9).

The morphologic features of microfilariae we observed were typical for M. ozzardi nematodes, and nested PCR confirmed detection of a DNA fragment (305 bp) known to be specific for this parasite. This assay used universal filariae PCR primers to amplify a variable portion of filarial parasite internal transcribed spacer 1 rDNA gene and enabled subsequent differentiation of species on the basis of the size of the amplified fragment (6). In addition, DNA was successfully extracted from scrapings of thick and thin dried blood films, even after long storage periods of 2–3 years.

We observed no microfilariae of M. perstans nematodes, and no positive samples showed DNA fragment sizes representative of this nematode (6). M. perstans nematodes have been reported only in the northern part of the Amazon rainforest from equatorial Brazil to the Caribbean coast of South America (1). In Colombia, M. perstans nematodes have been observed in a restricted area among the Curripacos Amerindians in the Comisaría del Guainia region bordering Venezuela (10), but have not been found in the Peruvian Amazon (1,2). However, further prospective studies using molecular techniques, are needed to clarify the epidemiologic status of this parasite.

In summary, we retrospectively identified human infection with M. ozzardi nematodes in the Amazon region of Ecuador. Our findings confirm that this parasite is endemic to this region.

Dr. Calvopina is a lecturer and associate research scientist at the Universidad de las Americas, Quito, Ecuador. His major research interest are exotic tropical parasites infections, including Amphimerus, Leishmania, and Paragonimus spp., and intestinal parasite infections.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ronald Guderian and Philip Cooper for reviewing the manuscript; and the Centro de Investigación en Epidemiología, Geomática, y Ciencias Afines, Instituto Nacional de Investigación en Salud Pública–Dr. Leopoldo Izquieta Pérez for preparing and providing information for Figure 1.

This study was supported by a grant (Proyecto MED.MC.18.01) from the Universidad de las Americas.

References

- Ta-Tang TH, Crainey JL, Post RJ, Luz SL, Rubio JM. Mansonellosis: current perspectives. Res Rep Trop Med. 2018;9:9–24. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Lima NF, Veggiani Aybar CA, Dantur Juri MJ, Ferreira MU. Mansonella ozzardi: a neglected New World filarial nematode. Pathog Glob Health. 2016;110:97–107. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Gobbi F, Beltrame A, Buonfrate D, Staffolani S, Degani M, Gobbo M, et al. Imported Infections with Mansonella perstans nematodes, Italy. Emerg Infect Dis. 2017;23:1539–42. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Tavares da Silva LB, Crainey JL, Ribeiro da Silva TR, Suwa UF, Vicente AC, Fernandes de Medeiros J, et al. Molecular verification of New World Mansonella perstans parasitemias. Emerg Infect Dis. 2017;23:545–7. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. DPDx: laboratory identification of parasites of public health concern [cited 2019 Aug 13]. https://www.cdc.gov/dpdx/index.html

- Tang TH, López-Vélez R, Lanza M, Shelley AJ, Rubio JM, Luz SL. Nested PCR to detect and distinguish the sympatric filarial species Onchocerca volvulus, Mansonella ozzardi and Mansonella perstans in the Amazon Region. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2010;105:823–8. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Suenaga E, Nakamura H. Evaluation of three methods for effective extraction of DNA from human hair. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2005;820:137–41. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Marinkelle CJ, German E. Mansonelliasis in the Comisaría del Vaupes of Colombia. [in Spanish]. Trop Geogr Med. 1970;22:101–11.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Medeiros JF, Almeida TA, Silva LB, Rubio JM, Crainey JL, Pessoa FA, et al. A field trial of a PCR-based Mansonella ozzardi diagnosis assay detects high-levels of submicroscopic M. ozzardi infections in both venous blood samples and FTA card dried blood spots. Parasit Vectors. 2015;8:280. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Kozek WJ, D’Alessandro A, Hoyos M. Filariasis in Colombia: presence of Dipetalonema perstans in the Comisaría del Guainía. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1982;31:486–9. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

Figures

Cite This ArticleOriginal Publication Date: September 27, 2019

Table of Contents – Volume 25, Number 11—November 2019

| EID Search Options |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Please use the form below to submit correspondence to the authors or contact them at the following address:

Manuel Calvopina, Universidad de las Américas, Jose Queri s/n, y Av. Granados, PO Box 17-17-9788, Quito, Ecuador

Top