Volume 25, Number 6—June 2019

Research Letter

Highly Pathogenic Swine Getah Virus in Blue Foxes, Eastern China, 2017

Abstract

We isolated Getah virus from infected foxes in Shandong Province, eastern China. We sequenced the complete Getah virus genome, and phylogenetic analysis revealed a close relationship with a highly pathogenic swine epidemic strain in China. Epidemiologic investigation showed that pigs might play a pivotal role in disease transmission to foxes.

Getah virus (GETV; genus Alphavirus, family Togaviridae) is a mosquitoborne RNA virus that causes death in young piglets, miscarriage in pregnant sows, and mild illness in horses (1–3). Serologic surveys show that the infection might occur in cattle, ducks, and chickens (4); some evidence suggests that GETV can infect humans and cause mild fever (5,6).

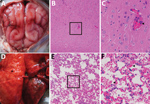

In September 2017, twenty-five 5-month-old blue foxes at a farm in Shandong Province in eastern China showed symptoms of sudden fever, anorexia, and depression; 6 of the 25 animals had onset of neurologic symptoms and died on the third day of illness. We collected blood samples from 45 healthy and 25 ill foxes. We subjected the tissue samples from dead animals, including the brains, lungs, spleens, kidneys, livers, intestines, hearts, and stomachs, to hematoxylin and eosin staining. Microscopic examination confirmed the presence of typical lesions in cerebral cortices with mild neuronal degeneration and inflammatory cell infiltration in vessels, as well as severe hemorrhagic pneumonia, congestion, and hemorrhage with a large number of erythrocytes in the alveolar space (Figure) (1). No obvious lesions were found in other organs.

We used supernatants of homogenized brain and lung tissues from each dead fox to inoculate Vero cells, as described previously (7). We observed a cytopathogenic effect within 72 hours. We observed numerous spherical, enveloped viral particles, ≈70 nm in diameter, after negative staining in a transmission electron microscope. To identify potential viral pathogens, we performed reverse transcription PCR (RT-PCR) to detect a panel of viruses, including canine distemper virus, canine parvovirus, canine coronavirus, and canine adenovirus. However, we detected none of these classical endemic viruses.

During the investigation, farmers reported that the foxes had been fed on organs from symptomatic pigs. We therefore tested for the presence of African swine fever virus, pseudorabies virus, porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus, classical swine fever virus, Japanese encephalitis virus, porcine circovirus type 2, porcine circovirus type 3, porcine cytomegalovirus, and alphavirus by using the primers for those viruses (Appendix Table 2). RT-PCR using universal primers for alphavirus (M2w-cMw3) produced a 434-bp amplicon when we tested all samples from dead foxes. Sanger sequencing of the amplicon and a BLAST search (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi) identified the sequence as that of GETV.

To further investigate the epidemic GETV infection, we performed quantitative RT-PCR by using RNA from all fox samples, as described elsewhere (7). Lung samples from all 6 dead foxes were positive, whereas only 2 samples from the remaining 19 ill foxes were also positive. None of the samples from healthy foxes were positive (Appendix Tables 1, 3). We measured serologic neutralizing antibodies by using a GETV isolate from a symptomatic fox, as previously described (8,9). Results showed no neutralizing antibody (<1:2) in healthy blue foxes (group 1) and variable levels of neutralizing antibodies (1:2 to 1:256) in ill foxes (groups 2–4) (Appendix Table 3). Samples from ill foxes with lower antibody titers had higher copies of RNA (groups 2–4). Spearman correlation analysis revealed a significant negative correlation between antibody titers and viral RNA copy numbers (r2 = 0.952; p<0.01).

We obtained the complete genome of the novel GETV SD1709 strain (GenBank accession no. MH106780) by using a conventional RT-PCR method (10). SD1709 genome sequence comparisons showed high identity with the porcine GETV strain (HuN1) at the nucleotide (99.6%) and deduced amino acid (99.7%–99.8%) sequences (Appendix Table 4). Furthermore, phylogenetic analysis of the complete genome and structural protein E2 gene indicated that the SD1709 strain was most similar to the recent epidemic HuN1 strain, which had caused large numbers of piglet deaths, stillbirths, and fetal mummies in southern China in 2017 (1) (Appendix Figures 1, 2).

We also detected GETV infection in pig serum samples and in mosquitoes (Culex tritaeniorhynchus, Anopheles sinensis, and Armigeres subalbatus) collected in the same region. The infection rate in pigs detected by quantitative RT-PCR was 20.0% (4/20) and by serum neutralization was 75.0% (15/20). The minimum infection rate in mosquitoes was ≈1.09%; C. tritaeniorhynchus mosquitoes had a higher minimum infection rate (2.31%) compared with other mosquito species (0–0.80%). These results suggest that pigs and C. tritaeniorhynchus mosquitoes might play a role in transmitting highly pathogenic GETV to captive foxes in this region (Appendix Tables 5, 6).

In China, the disease caused by GETV has only been reported in pigs in Hunan Province, although the virus has been detected in mosquitoes in >10 provinces (1,4). Our study provides evidence that GETV can cause lethal infection in blue foxes. Investigation of transmission routes for GETV in animals might help to prevent outbreaks of GETV disease in China.

Dr. Shi is a researcher at the School of Life Sciences and Engineering, Foshan University, Foshan, Guangdong Province, China. His research interests include emerging mosquitoborne infectious diseases.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ningyi Jin and Quan Liu for their discussions and suggestions.

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (grant no. 2017YFD0500104), the National Natural Sciences Foundation of China (grant no. 31802199), and the Key Laboratory for Preventive Research of Emerging Animal Diseases in Foshan University (grant no. KLPREAD201801-07).

References

- Yang T, Li R, Hu Y, Yang L, Zhao D, Du L, et al. An outbreak of Getah virus infection among pigs in China, 2017. Transbound Emerg Dis. 2018;65:632–7. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Yago K, Hagiwara S, Kawamura H, Narita M. A fatal case in newborn piglets with Getah virus infection: isolation of the virus. Nippon Juigaku Zasshi. 1987;49:989–94. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Nemoto M, Bannai H, Tsujimura K, Kobayashi M, Kikuchi T, Yamanaka T, et al. Getah virus infection among racehorses, Japan, 2014. Emerg Infect Dis. 2015;21:883–5. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Li Y, Fu S, Guo X, Li X, Li M, Wang L, et al. Serological survey of Getah virus in domestic animals in Yunnan Province, China. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2019;19:59–61. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Li XD, Qiu FX, Yang H, Rao YN, Calisher CH, Calisher CH. Isolation of Getah virus from mosquitos collected on Hainan Island, China, and results of a serosurvey. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 1992;23:730–4.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Marchette NJ, Rudnick A, Garcia R. Alphaviruses in Peninsular Malaysia: II. Serological evidence of human infection. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 1980;11:14–23.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Shi N, Liu H, Li LX, Hu B, Zhang L, Zhao CF, et al. Development of a TaqMan probe-based quantitative reverse transcription PCR assay for detection of Getah virus RNA. Arch Virol. 2018;163:2877–81. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Kuwata R, Shimoda H, Phichitraslip T, Prasertsincharoen N, Noguchi K, Yonemitsu K, et al. Getah virus epizootic among wild boars in Japan around 2012. Arch Virol. 2018;163:2817–21. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Bannai H, Nemoto M, Niwa H, Murakami S, Tsujimura K, Yamanaka T, et al. Geospatial and temporal associations of Getah virus circulation among pigs and horses around the perimeter of outbreaks in Japanese racehorses in 2014 and 2015. BMC Vet Res. 2017;13:187. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Li YY, Liu H, Fu SH, Li XL, Guo XF, Li MH, et al. From discovery to spread: The evolution and phylogeny of Getah virus. Infect Genet Evol. 2017;55:48–55. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

Figure

Cite This ArticleOriginal Publication Date: May 03, 2019

Table of Contents – Volume 25, Number 6—June 2019

| EID Search Options |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Please use the form below to submit correspondence to the authors or contact them at the following address:

Hao Liu, Foshan University, School of Life Sciences and Engineering, 18 Jiangwan First Rd, Chancheng District, Foshan, Guangdong 528000, China

Top