Volume 25, Number 8—August 2019

Dispatch

Marburgvirus in Egyptian Fruit Bats, Zambia

Figure

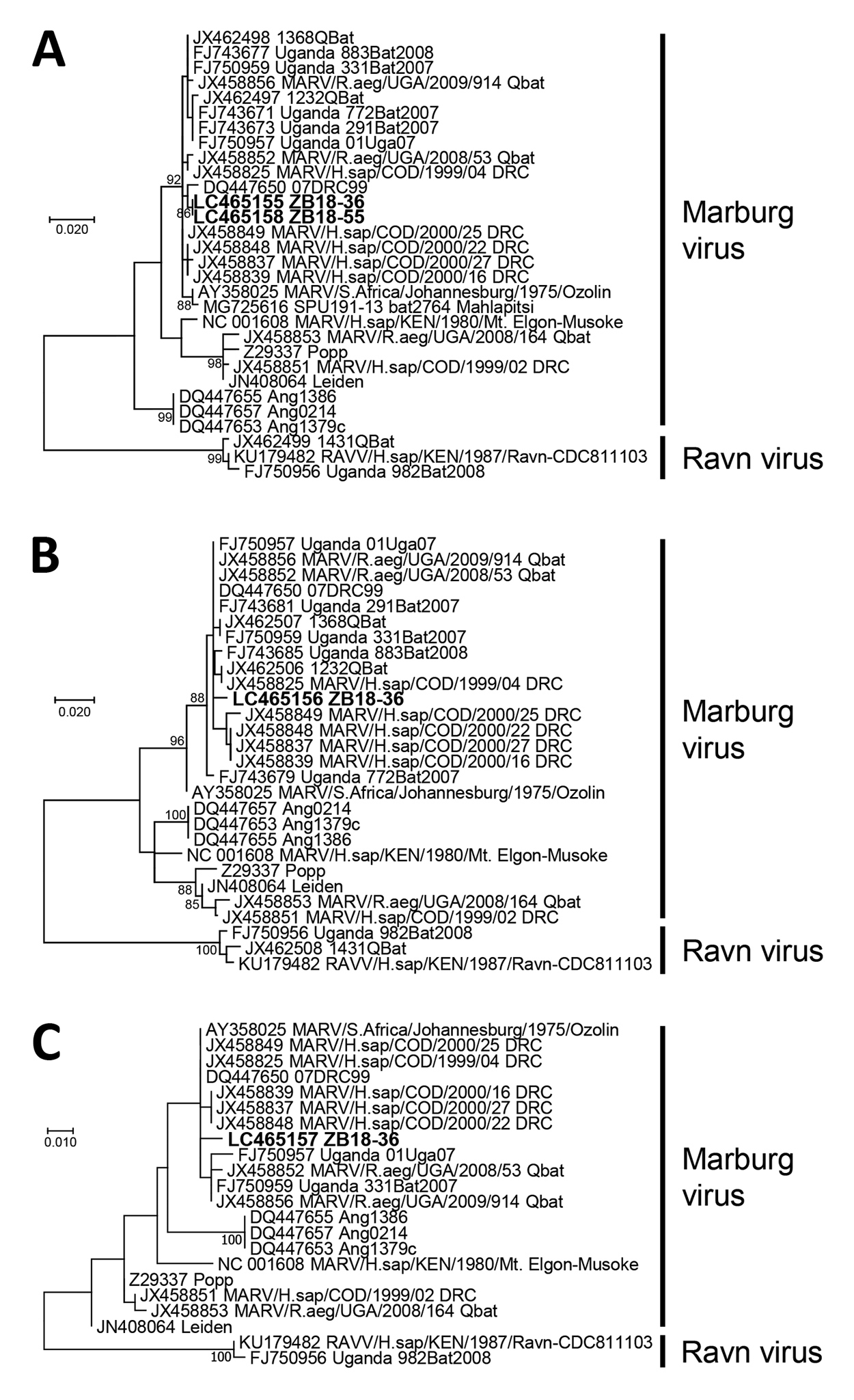

Figure. Phylogenetic trees showing evolutionary relationships of Marburgviruses from Egyptian fruit bats (Rousettus aegyptiacus), Zambia, 2018 (boldface), and reference viruses. The trees were constructed based on nucleotide sequences of 440 nt for the nucleoprotein gene (A), 296 nt for the viral protein 35 gene (B), and 238 nt for the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase gene (C) by using the maximum-likelihood method in MEGA7 (11). Nucleotide sequences of representative Marburgvirus strains were obtained from GenBank; accession numbers are shown with strain names. Bootstrap values >80 are shown near the branch nodes. Scale bars indicate nucleotide substitutions per site.

References

- Amarasinghe GK, Aréchiga Ceballos NG, Banyard AC, Basler CF, Bavari S, Bennett AJ, et al. Taxonomy of the order Mononegavirales: update 2018. Arch Virol. 2018;163:2283–94. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Outbreaks chronology: Marburg hemorrhagic fever. 2019 [cited 2019 Jan 29]. https://www.cdc.gov/vhf/marburg/outbreaks/chronology.html

- Changula K, Kajihara M, Mweene AS, Takada A. Ebola and Marburg virus diseases in Africa: increased risk of outbreaks in previously unaffected areas? Microbiol Immunol. 2014;58:483–91. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Swanepoel R, Smit SB, Rollin PE, Formenty P, Leman PA, Kemp A, et al.; International Scientific and Technical Committee for Marburg Hemorrhagic Fever Control in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Studies of reservoir hosts for Marburg virus. Emerg Infect Dis. 2007;13:1847–51. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Towner JS, Amman BR, Sealy TK, Carroll SA, Comer JA, Kemp A, et al. Isolation of genetically diverse Marburg viruses from Egyptian fruit bats. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:

e1000536 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Amman BR, Carroll SA, Reed ZD, Sealy TK, Balinandi S, Swanepoel R, et al. Seasonal pulses of Marburg virus circulation in juvenile Rousettus aegyptiacus bats coincide with periods of increased risk of human infection. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8:

e1002877 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - AfricanBats NPC, African Chiroptera Project. African Chiroptera Report 2018. Pretoria (South Africa): AfricanBats NPC; 2018.

- Changula K, Kajihara M, Mori-Kajihara A, Eto Y, Miyamoto H, Yoshida R, et al. Seroprevalence of filovirus infection of Rousettus aegyptiacus bats in Zambia. J Infect Dis. 2018;218(suppl5):S312–7.

- Ogawa H, Miyamoto H, Ebihara H, Ito K, Morikawa S, Feldmann H, et al. Detection of all known filovirus species by reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction using a primer set specific for the viral nucleoprotein gene. J Virol Methods. 2011;171:310–3. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Pawęska JT, Jansen van Vuren P, Kemp A, Storm N, Grobbelaar AA, Wiley MR, et al. Marburg virus infection in Egyptian rousette bats, South Africa, 2013–2014. Emerg Infect Dis. 2018;24:1134–7. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Kumar S, Stecher G, Tamura K. MEGA7: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol Biol Evol. 2016;33:1870–4. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Schuh AJ, Amman BR, Jones ME, Sealy TK, Uebelhoer LS, Spengler JR, et al. Modelling filovirus maintenance in nature by experimental transmission of Marburg virus between Egyptian rousette bats. Nat Commun. 2017;8:14446. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Hayman DTS. Biannual birth pulses allow filoviruses to persist in bat populations. Proc Biol Sci. 2015;282:20142591.

- Schindell BG, Webb AL, Kindrachuk J. Persistence and sexual transmission of filoviruses. Viruses. 2018;10:

E683 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

Page created: July 17, 2019

Page updated: July 17, 2019

Page reviewed: July 17, 2019

The conclusions, findings, and opinions expressed by authors contributing to this journal do not necessarily reflect the official position of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, the Public Health Service, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, or the authors' affiliated institutions. Use of trade names is for identification only and does not imply endorsement by any of the groups named above.