Volume 26, Number 12—December 2020

Dispatch

Shedding of Marburg Virus in Naturally Infected Egyptian Rousette Bats, South Africa, 2017

Cite This Article

Citation for Media

Abstract

We detected Marburg virus RNA in rectal swab samples from Egyptian rousette bats in South Africa in 2017. This finding signifies that fecal contamination of natural bat habitats is a potential source of infection for humans. Identified genetic sequences are closely related to Ravn virus, implying wider distribution of Marburg virus in Africa.

The genus Marburgvirus, family Filoviridae, comprises 1 species, Marburg marburgvirus, which comprises 2 marburgviruses, Marburg virus (MARV) and Ravn virus (RAVV) (1). Marburgviruses cause sporadic but often fatal MARV disease in humans and nonhuman primates (2). The Egyptian rousette bat (Rousettus aegyptiacus) has been implicated as the primary reservoir for marburgviruses (3–9), but the mechanisms by which they are maintained in these bats remain elusive. Evidence of marburgvirus circulation was reported from countries where MARV disease outbreaks have not been recorded (10–12). Determining the risks for spread and developing evidence-based public health strategies to prevent zoonotic transmission requires up-to-date knowledge about marburgvirus geographic range; genetic diversity; and transmission mechanisms, including natural ports of entry and shedding patterns. To clarify which marburgviruses are circulating and how they are maintained in Egyptian rousette bat populations in South Africa, we tested oral and rectal swab samples and blood samples collected during a previously identified peak season of marburgvirus transmission in a local Egyptian rousette bat population (13).

We conducted this work in accordance with approved protocols by animal ethics committees of the National Health Laboratory Service (Johannesburg, South Africa; AEC 137/12) and the University of Pretoria (Pretoria, South Africa; EC054–14). During February–November 2017, a total of 1,674 Egyptian rousette bats (February, 107 bats; April, 600; May, 563; September, 214; November, 190) were captured, aged, and sampled at Matlapitsi Cave, Limpopo Province, South Africa, as described previously (13). We collected and processed oral and rectal swab samples from each bat and blood from a subset of 423 bats, as described previously (7). Swab samples were collected and pooled by aliquoting 4 × 25 μL of the media of each sample into a microcentrifuge tube, yielding a total of 416 pools containing 100 μL of pooled rectal swab samples and 4 pools containing 50 or 75 μL of pooled oral swab samples. We conducted serologic, virologic, and molecular tests as described previously (7). In addition, we conducted real-time quantitative reverse transcription PCR (qRT-PCR) for individual swab samples when the pool tested positive. We prepared sequencing libraries using the TruSeq RNA Access Kit (Illumina, https://www.illumina.com) with MARV-specific bait enrichment, followed by sequencing on an Illumina NextSeq, genomic alignment and phylogenetic analysis (13). We calculated the significance of differences in several positive swab samples and seropositivity using the Fisher exact test in Stata version 13 (StataCorp, https://www.stata.com).

Seven rectal swab pools (5 from April 2017 and 2 from September 2017) were qRT-PCR positive; the remaining rectal swab samples collected during February–November 2017 were all negative. The number of individual positive rectal swab samples ranged from 1 to 3 per positive pool, totaling 11 positive samples. Only 1 oral swab sample pool, from April 2017, yielded a positive qRT-PCR result, containing a single positive oral swab sample (Table 1). Of 600 rectal swab samples collected during 3 nights in April, 9 (1.5%) were positive; of 215 rectal swab samples collected during 2 nights in September, 2 (0.9%) were positive. We found no significant difference between the number of positive rectal swab samples collected in April and the number collected September. The number of positive rectal swab samples differed significantly from the number of positive oral swab samples collected in April (p = 0.02). Attempts to culture marburgvirus from qRT-PCR–positive swab samples were unsuccessful. Identical results from specimens with cycle threshold (Ct) >30 were obtained in other studies (6,13).

We obtained sufficient marburgvirus-specific sequence data only from 1 of the 12 individual positive swab samples for phylogenetic analysis: a rectal swab sample, collected from a juvenile female (bat 8095) in September 2017, from which we recovered 79.2% (15.1/19.1 kb) of the genome. We merged sequencing reads from replicate sequencing runs and mapped 2,472 reads to the MARV reference genome. Maximum coverage per base obtained was 291 reads; some regions had no coverage. The average coverage per base across the genome was 18.5 reads (when we included 0 coverage regions), and the average coverage when we excluded 0 coverage regions was 40 reads. We obtained near-complete coding sequences for the viral protein (VP) 35 (972/990 nt; 98.2%) and VP40 (898/912 nt; 98.5%) genes; coverage ranged from 49.7% (VP24) to 89.3% (glycoprotein) in other open reading frames of the genome.

The marburgviruses sequence (strain RSA-2017-bat8095) detected from the rectal swab sample of bat 8095 shared a common ancestor with all other RAVV complete or near-complete genome sequences, including 3 human isolates from Kenya (14), Uganda (15), and the Democratic Republic of Congo (3) and several bat isolates from Uganda (4) (Figure 1). The RSA-2017-bat8095 nt sequence shared »77% identity with the MARV SPU191–13bat2764 Mahlapitsi strain (GenBank accession no. MG725616) that was collected and characterized from Matlapitsi Cave 4 years earlier.

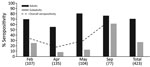

Of 423 bats tested, 143 (33.8%) were positive for antibodies against marburgviruses (73 adults and 70 juveniles). Lowest overall seroprevalence occurred in April 2017 (17.78%) and ranged from 8.3% in juveniles (9/108) to 55.6% in adults (15/27) (Figure 2). Overall seropositivity did not differ significantly between male and female bats, but the overall seropositivity differed significantly between juvenile (forearm <89 mm; <1-year-old) and adult bats (p = 0.03). We detected seroconversion in 6 (33.3%) of 18 recaptured bats (Table 2).

The period of the lowest seropositivity in juveniles (April–May) resulting in the highest number of potentially susceptible bats at Matlapitsi Cave was the same as previously identified (13). This finding coincides with demonstrable seroconversions and virus shedding and represents a period of increased exposure. The significantly higher number of marburgvirus-positive rectal than oral swab samples we detected contrasts with results from experimentally infected Egyptian rousette bats and field studies in Uganda (4,8,9). Experimental data on marburgvirus shedding were obtained from subcutaneously inoculated and colonized Egyptian rousette bats (7–9). Whether this mode of infection represents a natural portal of entry for marburgviruses in Egyptian rousette bats and to what extent viral shedding patterns in colonized bats can be extrapolated to natural settings are unknown.

Our findings highlight the risk for marburgvirus fecal environmental contamination and for Egyptian rousette bat roosting sites as a possible source of virus spillover. Roosting behavior enabling direct physical contact suggests that fecal–oral transmission of marburgviruses in bats can occur. Biting among animals or biting by hematophagous ectoparasites might result in inoculation of wounds with contaminated feces or exposure to contaminated fomites.

Our findings, combined with earlier detection of an Ozolin-like MARV in Egyptian rousette bats roosting at Matlapitsi Cave (13), suggest local co-circulation of multiple marburgviruses genetic variants. Detection of RAVV in South Africa, closely related to East African isolates, indicates that long-distance movement of Egyptian rousette bats contributes to widespread geographic dispersion of marburgviruses. Moreover, it implies that more virulent strains, such as the MARV Angolan strain (2), might be co-circulating. Entering caves and mining have been associated with MARV spillover (3–6,14,15) and detection of viral RNA in rectal swab samples, highlight the potential route of transmission. Confirmation of the period for the highest virus exposure risk further highlights the value of biosurveillance and demonstrates that marburgviruses continue endemic circulation in South Africa. This circulation represents a potential threat that needs to be communicated to at-risk communities as a part of evidence-based public health education and prevention of pathogen spillover.

Dr. Paweska is head of the Center for Emerging Zoonotic and Parasitic Diseases at the National Institute for Communicable Diseases, Johannesburg, South Africa. His research interests include diagnostic testing, epidemiology, and ecology of Biosafety Level 4 zoonotic viral agents.

Acknowledgments

We thank the students of the Centre for Viral Zoonoses, University of Pretoria, and the staff of the Center for Emerging Zoonotic and Parasitic Diseases, National Institute for Communicable Diseases of the National Health Laboratory Service, for technical assistance during field work. We also thank the Ga Mafefe community in the Limpopo Province for supporting our research at Matlapitsi Cave.

This work was supported by the South African National Research Foundation (grant no. UID 98339); the Poliomyelitis Research Foundation (grant no.12/14); the Division of Global Disease Detection, Center for Global Health, US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, under Cooperative Agreement no. 5, NU2GGH001874-02-00; the US Defense Threat Reduction Agency (CB10246); and the US Defense Biological Product Assurance Office through task order award (FA4600-12-D-9000).

References

- Amarasinghe GK, Aréchiga Ceballos NG, Banyard AC, Basler CF, Bavari S, Bennett AJ, et al. Taxonomy of the order Mononegavirales: update 2018. Arch Virol. 2018;163:2283–94. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Amman BR, Swanepoel R, Nichol ST, Towner JS. Ecology of Filoviruses. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2017;411:23–61. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Bausch DG, Nichol ST, Muyembe-Tamfum JJ, Borchert M, Rollin PE, Sleurs H, et al.; International Scientific and Technical Committee for Marburg Hemorrhagic Fever Control in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Marburg hemorrhagic fever associated with multiple genetic lineages of virus. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:909–19. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Towner JS, Amman BR, Sealy TK, Carroll SAR, Comer JA, Kemp A, et al. Isolation of genetically diverse Marburg viruses from Egyptian fruit bats. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:

e1000536 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Towner JS, Khristova ML, Sealy TK, Vincent MJ, Erickson BR, Bawiec DA, et al. Marburgvirus genomics and association with a large hemorrhagic fever outbreak in Angola. J Virol. 2006;80:6497–516. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Amman BR, Carroll SA, Reed ZD, Sealy TK, Balinandi S, Swanepoel R, et al. Seasonal pulses of Marburg virus circulation in juvenile Rousettus aegyptiacus bats coincide with periods of increased risk of human infection. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8:

e1002877 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Paweska JT, Jansen van Vuren P, Fenton KA, Graves K, Grobbelaar AA, Moolla N, et al. Lack of Marburg virus transmission from experimentally infected to susceptible in-contact Egyptian fruit bats. J Infect Dis. 2015;212(Suppl 2):S109–18. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Amman BR, Jones MEB, Sealy TK, Uebelhoer LS, Schuh AJ, Bird BH, et al. Oral shedding of Marburg virus in experimentally infected Egyptian fruit bats (Rousettus aegyptiacus). J Wildl Dis. 2015;51:113–24. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Schuh AJ, Amman BR, Jones ME, Sealy TK, Uebelhoer LS, Spengler JR, et al. Modelling filovirus maintenance in nature by experimental transmission of Marburg virus between Egyptian rousette bats. Nat Commun. 2017;8:14446. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Towner JS, Pourrut X, Albariño CG, Nkogue CN, Bird BH, Grard G, et al. Marburg virus infection detected in a common African bat. PLoS One. 2007;2:

e764 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Kajihara M, Hang’ombe BM, Changula K, Harima H, Isono M, Okuya K, et al. Marburgvirus in Egyptian fruit bats, Zambia. Emerg Infect Dis. 2019;25:1577–80. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Amman BR, Bird BH, Bakarr IA, Bangura J, Schuh AJ, Johnny J, et al. Isolation of Angola-like Marburg virus from Egyptian rousette bats from West Africa. Nat Commun. 2020;11:510. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Pawęska JT, Jansen van Vuren P, Kemp A, Storm N, Grobbelaar AA, Wiley MR, et al. Marburg virus infection in Egyptian rousette bats, South Africa, 2013–2014. Emerg Infect Dis. 2018;24:1134–7. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Johnson ED, Johnson BK, Silverstein D, Tukei P, Geisbert TW, Sanchez AN, et al. Characterization of a new Marburg virus isolated from a 1987 fatal case in Kenya. Arch Virol Suppl. 1996;11:101–14. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Adjemian J, Farnon EC, Tschioko F, Wamala JF, Byaruhanga E, Bwire GS, et al. Outbreak of Marburg hemorrhagic fever among miners in Kamwenge and Ibanda Districts, Uganda, 2007. J Infect Dis. 2011;204(Suppl 3):S796–9. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

Figures

Tables

Cite This ArticleOriginal Publication Date: November 11, 2020

Table of Contents – Volume 26, Number 12—December 2020

| EID Search Options |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Please use the form below to submit correspondence to the authors or contact them at the following address:

Janusz T. Pawęska, Center for Emerging Zoonotic and Parasitic Diseases, National Institute for Communicable Diseases of the National Health Laboratory Service, 1 Modderfontein Rd, Sandringham 2131, Johannesburg, South Africa

Top