Volume 27, Number 9—September 2021

Synopsis

Epidemiology, Clinical Features, and Outcomes of Coccidioidomycosis, Utah, 2006–2015

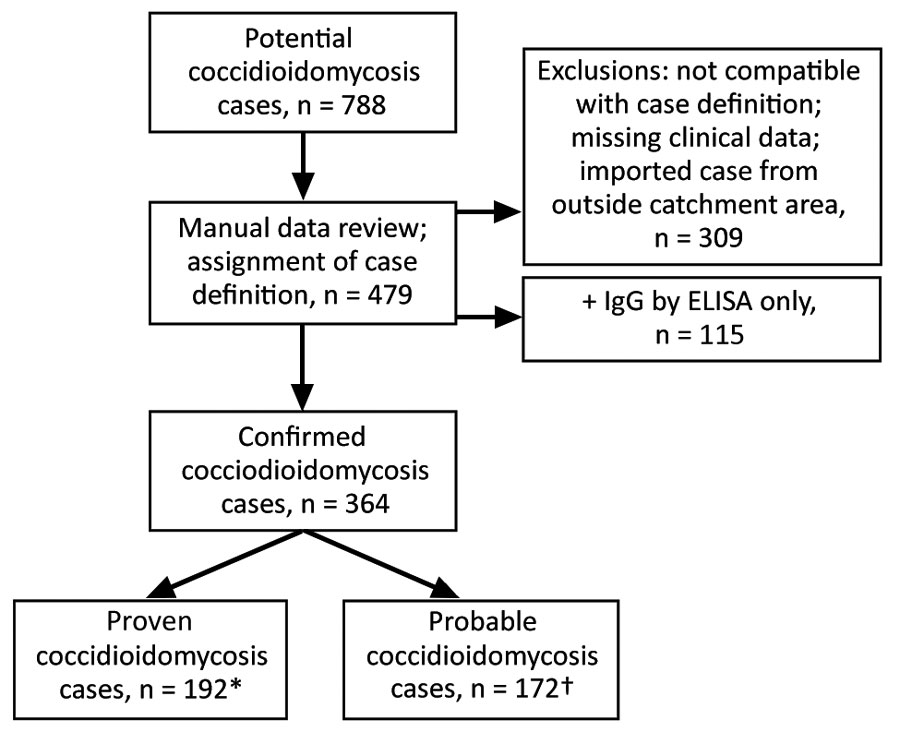

Figure 1

Figure 1. Flowchart showing process for inclusion of possible coccidioidomycosis studies in study of cases in Utah, 2006–2015. Confirmed cases had ≥1 of the following: 1) histopathological, cytopathological, or direct microscopic evidence of Coccidioides spherules with tissue damage from sterile specimen or tissue biopsy; 2) culture from any specimen or tissue biopsy positive for C. immitis or C. posadasii; 3) blood culture positive for C. immitis or C. posadasii; 4) positive Coccidioides serology in cerebrospinal fluid; or 5) two-dilution rise in Coccidioides CF titer measured in consecutive blood samples tested concurrently. Probable cases had a Coccidioides complement fixation titer >1:2 or positive IgM or IgG by EIA/ELISA or immunodiffusion in the setting of a compatible clinical syndrome and ≥1 of the following: 1) systemic infection with fever, chills, night sweats, weight loss; 2) cutaneous or musculoskeletal infection; 3) pulmonary involvement with nodules, cavitation, hilar lymphadenopathy; 4) meningitis; or 5) visceral infiltration. Definitions based on criteria set by the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer/Invasive Fungal Infections Cooperative Group; National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Mycoses Study Group (10).

References

- Pappagianis D. Epidemiology of coccidioidomycosis. In: McGinnis M, editor. Current topics in medical mycology, vol. 2. New York City: Springer; 1988. p. 199–238.

- Galgiani JN, Ampel NM, Blair JE, Catanzaro A, Geertsma F, Hoover SE, et al. 2016 Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) clinical practice guideline for the treatment of coccidioidomycosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63:e112–46. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Edwards PQ, Palmer CE. Prevalence of sensitivity to coccidioidin, with special reference to specific and nonspecific reactions to coccidioidin and to histoplasmin. Dis Chest. 1957;31:35–60. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Increase in reported coccidioidomycosis—United States, 1998-2011. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013;62:217–21.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Coccidioidomycosis in workers at an archeologic site—Dinosaur National Monument, Utah, June–July 2001. JAMA. 2001;286:3072–3. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Perera P, Stone S. Update on emerging infections: news from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Ann Emerg Med. 2002;39:566–9.

- Petersen LR, Marshall SL, Barton-Dickson C, Hajjeh RA, Lindsley MD, Warnock DW, et al. Coccidioidomycosis among workers at an archeological site, northeastern Utah. Emerg Infect Dis. 2004;10:637–42. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Gorris ME, Cat LA, Zender CS, Treseder KK, Randerson JT. Coccidioidomycosis dynamics in relation to climate in the southwestern United States. Geohealth. 2018;2:6–24. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Webb BJFJ, Ferraro JP, Rea S, Kaufusi S, Goodman BE, Spalding J. Epidemiology and clinical features of invasive fungal infection in a US health care network. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2018;5:

ofy187 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - De Pauw B, Walsh TJ, Donnelly JP, Stevens DA, Edwards JE, Calandra T, et al.; European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer/Invasive Fungal Infections Cooperative Group; National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Mycoses Study Group (EORTC/MSG) Consensus Group. Revised definitions of invasive fungal disease from the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer/Invasive Fungal Infections Cooperative Group and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Mycoses Study Group (EORTC/MSG) Consensus Group. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46:1813–21. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Daly C, Halbleib M, Smith JI, Gibson WP, Doggett MK, Taylor GH, et al. Physiographically sensitive mapping of climatological temperature and precipitation across the conterminous United States. Int J Climatol. 2008;28:2031–64. DOIGoogle Scholar

- Daly C, Neilson RP, Phillips DL. A statistical‐topographic model for mapping climatological precipitation over mountainous terrain. J Appl Meteorol. 1994;33:140–58. DOIGoogle Scholar

- Kolivras KN, Comrie AC. Modeling valley fever (coccidioidomycosis) incidence on the basis of climate conditions. Int J Biometeorol. 2003;47:87–101. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Comrie AC. Climate factors influencing coccidioidomycosis seasonality and outbreaks. Environ Health Perspect. 2005;113:688–92. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Park BJ, Sigel K, Vaz V, Komatsu K, McRill C, Phelan M, et al. An epidemic of coccidioidomycosis in Arizona associated with climatic changes, 1998-2001. J Infect Dis. 2005;191:1981–7. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Weaver EA, Kolivras KN. Investigating the relationship between climate and valley fever (coccidioidomycosis). EcoHealth. 2018;15:840–52. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Cummings KC, McDowell A, Wheeler C, McNary J, Das R, Vugia DJ, et al. Point-source outbreak of coccidioidomycosis in construction workers. Epidemiol Infect. 2010;138:507–11. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Laws RL, Cooksey GS, Jain S, Wilken J, McNary J, Moreno E, et al. Coccidioidomycosis outbreak among workers constructing a solar power farm—Monterey County, California, 2016–2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67:931–4. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Wilken JA, Sondermeyer G, Shusterman D, McNary J, Vugia DJ, McDowell A, et al. Coccidioidomycosis among workers constructing solar power farms, California, USA, 2011–2014. Emerg Infect Dis. 2015;21:1997–2005. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Arizona Department of Health Services, Office of Infectious Disease Services. Rates of reported cases of notifiable diseases by year for Arizona, 2005–2015, per 100,000 population [cited 2019 Jun 19]. https://www.azdhs.gov/documents/preparedness/epidemiology-disease-control/disease-data-statistics-reports/data-statistics-archive/t3a1-rates.pdf

- California Department of Public Health, Division of Communicable Diseases Control, Infectious Diseases Branch, Surveillance and Statistics Section. Yearly summaries of selected general communicable diseases in California, 2001–2010 [cited 2019 Jun 19]. https://www.cdph.ca.gov/Programs/CID/DCDC/CDPH%20Document%20Library/YearlySummaryReportsofSelectedGenCommDiseasesinCA2001-2010.pdf

- California Department of Public Health, Division of Communicable Diseases Control, Infectious Diseases Branch, Surveillance and Statistics Section. Epidemiologic summary of coccidioidomycosis in California, 2016 [cited 2019 Jun 19]. https://www.cdph.ca.gov/Programs/CID/DCDC/CDPH%20Document%20Library/CocciEpiSummary2016.pdf

- Brown J, Benedict K, Park BJ, Thompson GR III. Coccidioidomycosis: epidemiology. Clin Epidemiol. 2013;5:185–97.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Taylor JW, Barker BM. The endozoan, small-mammal reservoir hypothesis and the life cycle of Coccidioides species. Med Mycol. 2019;57(Supplement_1):S16–20. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Huang JY, Bristow B, Shafir S, Sorvillo F. Coccidioidomycosis-associated Deaths, United States, 1990-2008. Emerg Infect Dis. 2012;18:1723–8. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Barker BM, Jewell KA, Kroken S, Orbach MJ. The population biology of coccidioides: epidemiologic implications for disease outbreaks. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2007;1111:147–63. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Odio CD, Marciano BE, Galgiani JN, Holland SM. Risk factors for disseminated coccidioidomycosis, United States. Emerg Infect Dis. 2017;23:308–11. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar