Volume 28, Number 3—March 2022

CME ACTIVITY - Synopsis

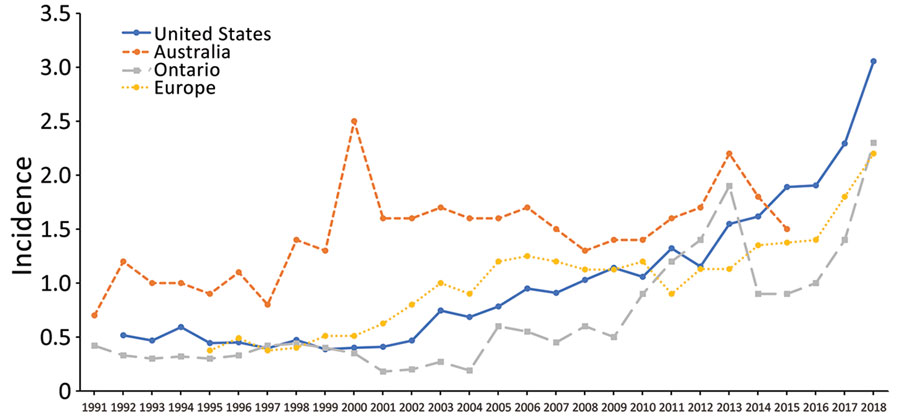

Rising Incidence of Legionnaires’ Disease and Associated Epidemiologic Patterns, United States, 1992–2018

Figure 8

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Legionnaires’ disease surveillance summary report, United States, 2016–2017. February 2020 [cited 2020 August 20]. https://www.cdc.gov/legionella/health-depts/surv-reporting/2016-17-surv-report-508.pdf

- Marston BJ, Lipman HB, Breiman RF. Surveillance for Legionnaires’ disease. Risk factors for morbidity and mortality. Arch Intern Med. 1994;154:2417–22. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Garrison LE, Kunz JM, Cooley LA, Moore MR, Lucas C, Schrag S, et al. Vital signs: deficiencies in environmental control identified in outbreaks of Legionnaires’ disease—North America, 2000–2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65:576–84. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers (ASHRAE). ANSI/ASHRAE Standard 188–2015, Legionellosis: risk management for building water systems. 2018 [cited 2020 August 20]. https://www.ashrae.org/technical-resources/bookstore/ansi-ashrae-standard-188-2018-legionellosis-risk-management-for-building-water-systems

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Toolkit: developing a water management program to reduce Legionella growth and spread in buildings. A practical guide to implementing industry standards. 2021 Mar 25 [cited 2021 June 8]. https://www.cdc.gov/legionella/maintenance/wmp-toolkit.html

- McDade JE, Shepard CC, Fraser DW, Tsai TR, Redus MA, Dowdle WR. Legionnaires’ disease: isolation of a bacterium and demonstration of its role in other respiratory disease. N Engl J Med. 1977;297:1197–203. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Fraser DW, Tsai TR, Orenstein W, Parkin WE, Beecham HJ, Sharrar RG, et al. Legionnaires’ disease: description of an epidemic of pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 1977;297:1189–97. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. MMWR summary of notifiable diseases, United States, 1993. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1994;42:1–73.

- Neil K, Berkelman R. Increasing incidence of legionellosis in the United States, 1990-2005: changing epidemiologic trends. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47:591–9. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Legionellosis --- United States, 2000-2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60:1083–6.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Alarcon Falconi TM, Cruz MS, Naumova EN. The shift in seasonality of legionellosis in the USA. Epidemiol Infect. 2018;146:1824–33. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Nationally notifiable infectious diseases and conditions, United States: Annual tables. Table 2i. Annual reported cases of notifiable diseases, by region and reporting area, United States and U.S. Territories, excluding non-U.S. residents, 2019 [cited 2021 May 25]. https://wonder.cdc.gov/nndss/static/2019/annual/2019-table2i.html

- Wharton M, Chorba TL, Vogt RL, Morse DL, Buehler JW. Case definitions for public health surveillance. MMWR Recomm Rep. 1990;39(RR-13):1–43.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Case definitions for infectious conditions under public health surveillance. MMWR Recomm Rep. 1997;46(RR-10):1–55.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists. Strengthening surveillance for travel-associated legionellosis and revised case definitions for legionellosis. Position statement no. 05-ID-01. 2005 Mar 31 [cited 2020 August 20]. https://cdn.ymaws.com/www.cste.org/resource/resmgr/PS/05-ID-01FINAL.pdf

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Bridged-race population estimates: data files and documentation. 2020 Jul 9 [cited 2020 August 20]. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/bridged_race/data_documentation.htm

- Howden LM, Meyer JA. Age and sex composition: 2010. 2010 Census briefs, C2010BR-03. 2011 May [cited 2021 May 26]. https://www.census.gov/prod/cen2010/briefs/c2010br-03.pdf

- Roberts AW, Ogunwole SU, Blakeslee L, Rabe MA. The population 65 years and older in the United States: 2016. 2018 Oct [cited 2021 May 26]. https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2018/acs/ACS-38.pdf

- Gaskin DJ, Thorpe RJ Jr, McGinty EE, Bower K, Rohde C, Young JH, et al. Disparities in diabetes: the nexus of race, poverty, and place. Am J Public Health. 2014;104:2147–55. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Bock F, Stewart TG, Robinson-Cohen C, Morse J, Kabagambe EK, Cavanaugh KL, et al. Racial disparities in end-stage renal disease in a high-risk population: the Southern Community Cohort Study. BMC Nephrol. 2019;20:308. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Kirtane K, Lee SJ. Racial and ethnic disparities in hematologic malignancies. Blood. 2017;130:1699–705. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Hunter CM, Salandy SW, Smith JC, Edens C, Hubbard B. Racial disparities in incidence of Legionnaires’ disease and social determinants of health: a narrative review. Public Health Rep. 2021;

333549211026781 ; Epub ahead of print. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Semega J, Kollar M, Creamer J, Mohanty A. Income and poverty in the United States: 2019. 2020 Sep [cited 2021 May 26]. https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2020/demo/p60-270.pdf

- Farnham A, Alleyne L, Cimini D, Balter S. Legionnaires’ disease incidence and risk factors, New York, New York, USA, 2002-2011. Emerg Infect Dis. 2014;20:1795–802. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Gleason JA, Ross KM, Greeley RD. Analysis of population-level determinants of legionellosis: spatial and geovisual methods for enhancing classification of high-risk areas. Int J Health Geogr. 2017;16:45. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Simmering JE, Polgreen LA, Hornick DB, Sewell DK, Polgreen PM. Weather-dependent risk for legionnaires’ disease, United States. Emerg Infect Dis. 2017;23:1843–51. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Fisman DN, Lim S, Wellenius GA, Johnson C, Britz P, Gaskins M, et al. It’s not the heat, it’s the humidity: wet weather increases legionellosis risk in the greater Philadelphia metropolitan area. J Infect Dis. 2005;192:2066–73. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Hicks LA, Rose CE Jr, Fields BS, Drees ML, Engel JP, Jenkins PR, et al. Increased rainfall is associated with increased risk for legionellosis. Epidemiol Infect. 2007;135:811–7. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Beauté J, Sandin S, Uldum SA, Rota MC, Brandsema P, Giesecke J, et al. Short-term effects of atmospheric pressure, temperature, and rainfall on notification rate of community-acquired Legionnaires’ disease in four European countries. [Erratum in: Epidemiol Infect. 2017;145:3319]. Epidemiol Infect. 2016;144:3483–93. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Passer JK, Danila RN, Laine ES, Como-Sabetti KJ, Tang W, Searle KM. The association between sporadic Legionnaires’ disease and weather and environmental factors, Minnesota, 2011-2018. Epidemiol Infect. 2020;148:

e156 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - National Centers for Environmental Information, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. National trends: temperature, precipitation, and drought [cited 2021 June 8]. https://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/temp-and-precip/us-trends/prcp/sum

- National Centers for Environmental Information, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. National temperature and precipitation maps [cited 2021 June 8]. https://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/temp-and-precip/us-maps

- Guzman O, Jiang H. Global increase in tropical cyclone rain rate. Nat Commun. 2021;12:5344. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Brigmon RL, Turick CE, Knox AS, Burckhalter CE. The impact of storms on Legionella pneumophila in cooling tower water, implications for human health. Front Microbiol. 2020;11:

543589 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Ulrich N, Rosenberger A, Brislawn C, Wright J, Kessler C, Toole D, et al. Restructuring of the aquatic bacterial community by hydric dynamics associated with superstorm Sandy. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2016;82:3525–36. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Barskey AE, Lackraj D, Tripathi PS, Lee S, Smith J, Edens C. Travel-associated cases of Legionnaires’ disease in the United States, 2015-2016. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2021;40:

101943 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Graham FF, Hales S, White PS, Baker MG. Review Global seroprevalence of legionellosis - a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2020;10:7337. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Surveillance reports on Legionnaires’ disease [cited 2021 June 8]. https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/legionnaires-disease/surveillance-and-disease-data/surveillance

- Ontario Agency for Health Protection and Promotion (Public Health Ontario). Factors affecting reportable diseases in Ontario (1991–2016) [cited 2020 August 20]. https://www.publichealthontario.ca/-/media/documents/f/2018/factors-reportable-diseases-ontario-1991-2016.pdf

- Public Health Ontario. Infectious disease trends in Ontario: Legionellosis [cited 2021 June 8]. https://www.publichealthontario.ca/en/data-and-analysis/infectious-disease/reportable-disease-trends-annually#/31

- Australian Government Department of Health. National notifiable diseases: Australia’s notifiable diseases status: annual report of the National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System. 2019 Mar [cited 2020 August 20]. https://www1.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/cda-pubs-annlrpt-nndssar.htm

- Dooling KL, Toews KA, Hicks LA, Garrison LE, Bachaus B, Zansky S, et al. Active Bacterial Core surveillance for legionellosis—United States, 2011–2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64:1190–3. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Collier SA, Deng L, Adam EA, Benedict KM, Beshearse EM, Blackstock AJ, et al. Estimate of burden and direct healthcare cost of infectious waterborne disease in the United States. Emerg Infect Dis. 2021;27:140–9. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Hui DSC, Zumla A. Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome: historical, epidemiologic, and clinical features. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2019;33:869–89. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Benin AL, Benson RF, Besser RE. Trends in legionnaires disease, 1980-1998: declining mortality and new patterns of diagnosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;35:1039–46. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Metlay JP, Waterer GW, Long AC, Anzueto A, Brozek J, Crothers K, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of adults with community-acquired pneumonia: an official clinical practice guideline of the American Thoracic Society and Infectious Diseases Society of America. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019;200:e45–67. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Hayes BH, Haberling DL, Kennedy JL, Varma JK, Fry AM, Vora NM. Burden of pneumonia-associated hospitalizations: United States, 2001–2014. Chest. 2018;153:427–37. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Leftwich B, Opoku S, Yin J, Adhikari A. Assessing hotel employee knowledge on risk factors and risk management procedures for microbial contamination of hotel water distribution systems. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18:3539. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Lapierre P, Nazarian E, Zhu Y, Wroblewski D, Saylors A, Passaretti T, et al. Legionnaires’ disease outbreak caused by endemic strain of Legionella pneumophila, New York, New York, USA, 2015. Emerg Infect Dis. 2017;23:1784–91. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

Page created: January 05, 2022

Page updated: February 17, 2022

Page reviewed: February 17, 2022

The conclusions, findings, and opinions expressed by authors contributing to this journal do not necessarily reflect the official position of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, the Public Health Service, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, or the authors' affiliated institutions. Use of trade names is for identification only and does not imply endorsement by any of the groups named above.