Volume 29, Number 12—December 2023

Research

Detection of Anopheles stephensi Mosquitoes by Molecular Surveillance, Kenya

Cite This Article

Citation for Media

Abstract

The Anopheles stephensi mosquito is an invasive malaria vector recently reported in Djibouti, Ethiopia, Sudan, Somalia, Nigeria, and Ghana. The World Health Organization has called on countries in Africa to increase surveillance efforts to detect and report this vector and institute appropriate and effective control mechanisms. In Kenya, the Division of National Malaria Program conducted entomological surveillance in counties at risk for An. stephensi mosquito invasion. In addition, the Kenya Medical Research Institute conducted molecular surveillance of all sampled Anopheles mosquitoes from other studies to identify An. stephensi mosquitoes. We report the detection and confirmation of An. stephensi mosquitoes in Marsabit and Turkana Counties by using endpoint PCR and morphological and sequence identification. We demonstrate the urgent need for intensified entomological surveillance in all areas at risk for An. stephensi mosquito invasion, to clarify its occurrence and distribution and develop tailored approaches to prevent further spread.

The Anopheles stephensi mosquito is a major vector of malaria in south Asia, the Middle East, and southern China, where it is endemic and is known to transmit both Plasmodium falciparum and P. vivax. This mosquito differs from other malaria vectors because of its ability to grow and reproduce in human-made containers in clean or contaminated water. Those traits have enabled An. stephensi mosquitoes to colonize urban settings, in addition to their native rural foci, where they can potentially sustain malaria transmission (1).

The An. stephensi mosquito was first reported in Djibouti in the Horn of Africa in 2012 (2). Since then, it has been reported in multiple urban and rural settings in Ethiopia, Sudan, Somalia, and Ghana (3–6) and could be responsible for sustaining malaria transmission in Ethiopia. The species has the potential to increase P. falciparum incidence by 50% according to recent mathematical modeling (7,8), as has been observed in Djibouti (9).

An. stephensi mosquitoes could spread south and west from their original foci of detection in the Horn of Africa, as has been observed in Nigeria (4) and Ghana (6). This vector has the potential to establish or increase transmission in urban settings where the malaria burden is generally lower than in rural settings, particularly in areas where poorly planned drainage and waste disposal systems create conducive larval habitats (10). The behavior of adult mosquitoes in their invasive range in Africa is not well understood, especially as they continue to colonize new areas in the continent, but their spread has been predicted using modeling (10).

The World Health Organization recently called for heightened surveillance and development of response strategies to limit the spread of this vector in Africa (4). The initiative highlights 5 key focus areas: increased collaboration across sectors and borders, strengthening surveillance, improving information exchange, developing national guidelines, and prioritizing research to evaluate tools against this vector. In Kenya, the Division of National Malaria Program (DNMP) at the Ministry of Health and its partners have been on high alert and instituted surveillance efforts after the World Health Organization initiative (4). Surveillance efforts have been focused along the Kenya coast and the northern counties bordering Sudan and Ethiopia. Current surveillance efforts are aimed at the collection of both larval and adult mosquito samples. Samples collected are identified using morphological keys and PCR at the reference laboratories located at the Kenya Medical Research Institute (KEMRI). Here we detail the process that led to detecting and identifying An. stephensi mosquitoes in Kenya.

Surveillance Sites

The DNMP and its partners collected mosquitoes in 14 counties in December 2022 as part of routine surveillance. Counties where DNMP supported vector surveillance in December 2022 were categorized as malaria endemic (Kilifi, Taita, and Taveta), highland epidemic prone (Elgeyo Marakwet, West Pokot, Kisii, and Nandi), low risk (Garissa, Makueni, Kajiado, Kirinyaga, and Laikipia), or seasonal (Marsabit, Baringo and Turkana) (Figure 1). For the purpose of this work, we present results for Marsabit and Turkana Counties, where samples were collected, identified, and confirmed to be An. stephensi mosquitoes. Marsabit and Turkana are neighboring counties in northern Kenya, located on either side of Lake Turkana. Marsabit County borders Ethiopia to the north, Turkana County to the west, Samburu County to the south, and Wajir and Isiolo Counties to the east. Turkana County borders Uganda to the west, South Sudan to the north, and Ethiopia to the northeast. Directly east lies Lake Turkana, and Marsabit lies just beyond. The counties lie 300–900 meters above sea level.

Mosquito sampling in Marsabit was conducted in the subcounties of Moyale, Laisamis, and Saku and focused on urban and rural settings along the northern transport corridor connecting Kenya and Ethiopia (Table 1). Sampling in Turkana focused on Lodwar, the capital of the county and a major town on the land transport corridor into Kenya. The main economic activities of the rural population are nomadic pastoralism because of the semiarid terrain; urban trade centers are set up along the northern transport corridor. Urban trade centers were the focus of the sampling efforts.

Sampling

We conducted mosquito sampling in Marsabit for adult and larval samples. We collected adult mosquitoes using US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) light traps and collected larvae by dipping. We set CDC light traps overnight indoors, next to a person sleeping under a bednet, or outside, 10 m from the structure without regard for the presence of animals, between 6 pm and 7 pm and collected them the next morning between 7 am and 8 am. In addition, we dipped for larvae in animal watering pens, containers, tires, and other standing water in the area (Figure 2). We collected Anopheles larvae and placed them in whirlpacks for transportation to the entomology laboratory at KEMRI for additional assays. The mosquitoes were reared in the infection room; the room was equipped with a triple door and curtains at the entrance and sealed windows to prevent escapees. Surviving larvae were reared to adults for morphologic identification using standard conditions (25 + 2°C; 80% + 4% relative humidity; 12 h/12 h light/dark cycle). We fed larvae on Tetramin baby fish food and brewer’s yeast daily and maintained adults on 10% sugar solution.

In Turkana, larval sampling focused on water pans near the seasonal river and cement water cisterns. We visited 11 suspected larval sites throughout the town every 2 weeks and dipped 5 times at each site to quantify larval density. We separated Anopheles larvae and placed them in tubes with 95% ethanol for shipment to the PEARL laboratory in Webuye. Collections occurred during November–December 2022.

Molecular Characterization

We isolated DNA from 55 mosquito carcasses (either whole or legs and wings) consisting of field-collected larvae or laboratory-reared F0 adults from larvae collected in Marsabit using the ethanol precipitation method (11) in the KEMRI Kisumu laboratory. We conducted amplification using an endpoint PCR assay that included 3 primers: St-F (5′-CGTATCTTTCCTCGCATCCA-3′), an An. stephensi–specific forward primer targeting the internal transcribed spacer 2 (ITS2) region; U5.8S-F (5′-ATCACTCGGCTCATGGATCG-3′). a universal forward primer flanking the conserved 5.8S rDNA region; and UD2-R (5′-GCACTATCAAGCAACACGACT-3′), a universal reverse primer flanking the conserved D2 domain of 28S rDNA (12). We performed the reactions using 0.15 µL of the DNA template alongside a positive control with the following set of cycling conditions: 95°C for 5 min, followed by 95 °C for 30 s, 55 °C for 30 s and 68 °C for 45 s for 30 cycles, and a final extension at 68 °C for 7 min. Thereafter, we ran 15 µL of each of the PCR products on 2% agarose gel alongside 3 µL of a 100-bp DNA ladder for size comparison. We visualized the products in the gel documentation system for an expected amplicon size of ≈438bp. This visualization was the primary method of identification given the relative inexperience of the laboratory teams in morphological identification of An. stephensi mosquitoes.

Samples collected in Turkana were processed at the AMPATH Laboratories in Eldoret, Kenya. We rinsed field-collected larval samples preserved in ethanol with nuclease-free water and pooled in groups of 3 from the same breeding site. We extracted triads in a single well of a 96-well plate using the Hotshot protocol, performed amplification using a previously published protocol (13) with corrected primer sequences, and visualized reactions on 2% agarose gels. If a band of the expected size was observed, we separated the larvae in the pool and extracted them individually using the DNeasy Blood and Tissue Kit (QIAGEN, https://www.qiagen.com), after which we repeated amplification and electrophoresis as previously described. We subsequently sequenced positive samples as described in the following section.

Morphologic Identification and Sequencing

We taxonomically identified emerging adults that were a subset of the larvae collected in Marsabit using the keys described by Coetzee et al. (14) to detect the distinct banding on the maxillary palps, pale scales on the scutum, and the 3 dark spots on wing vein 1A (Figure 3). We randomly selected 4 adult specimens that were a subset of the samples from Marsabit identified as An. stephensi mosquitoes by morphology and shipped them to CDC (Atlanta, GA, USA), where DNA from a single mosquito leg was extracted using the Extracta DNA Prep for PCR kit (Quantabio, https://www.quantabio.com). We performed amplification targeting the ITS2 (as previously described) and the cytochrome c oxidase subunit 1 gene (CO1) locus. For CO1 amplification, we used specific LCO1490F (5ʹ-GTTCAACAAATCATAAAGATATTGG-3ʹ) and HCO2198R (5ʹ-TAAACTTCAGGTGACCAAAAAATCA-3ʹ) primers (15). The PCR cycling conditions included an initial step at 95°C for 1 min, then 30 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 30 s, annealing at 48°C for 30 s, and extension at 72°C for 1 min. We ran Amplicons for both ITS2 and CO1 on a 2% agarose for confirmation, then used the positive PCR products for Sanger sequencing. We performed BLAST (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi) homology searches of both ITS2 and CO1 sequences using the default parameters to confirm the matching species.

We sequenced 4 larval samples from Lodwar after the ITS2 band was purified from the agarose gel at the KEMRI Wellcome Trust (Kilifi, Kenya). We constructed sequencing libraries using Oxford Nanopore Technologies Ligation Sequencing Kit and multiplexed samples using the Native Barcoding Expansion Kit (https://nanoporetech.com). We performed adaptor ligation on the barcoded amplicon pool and the final library loaded on a SpotON R9.4.1 flow cell and sequenced on the GridION (Oxford Nanopore Technologies).

Using SPADES assembler (16), we performed de novo assembly on the filtered reads. We performed species identification through a BLAST search using ITS2 sequences from GenBank as the subject database and the assembled contigs as the query dataset.

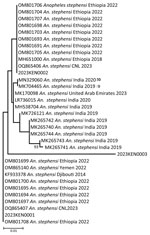

Phylogenetic Analyses

We constructed phylogenetic trees for both CO1 and ITS2 sequences by incorporating sequences from diverse isolates retrieved from GenBank along with isolates from Kenya. We used MAFFT software version 7.520 (17,18) for all sequence alignments and reconstructed maximum-likelihood phylogenies using the Bayesian Information Criterion with general time-reversible (GTR) as the best substitution model as inferred by jModelTest in IQ-TREE version 2.0.7 (19,20). We performed tree visualization using MEGA version 11 (21) and took the bootstrap consensus tree inferred from 1,000 replicates to reliably show the evolutionary history.

Molecular Surveillance Results

We collected Anopheles larvae from 11 locations in 3 subcounties in the 2 counties (Table 1). In Marsabit, a total of 59 larvae were collected. Of those, 11 died in transit and were immediately prepared for PCR identification using the An. stephensi protocol; 7 were confirmed as An. stephensi mosquitoes (Table 2). We pooled the 48 remaining larvae by subcounty to rear adult samples. Of the first 12 samples that emerged, we identified 9 adults by morphology (Figure 3). We correctly identified 7 of the 9 samples as An. stephensi mosquitoes, which were later confirmed by PCR through ITS2 amplification (Table 2). The other 2 were identified as An. gambiae mosquitoes by morphology but were confirmed to be An. stephensi mosquitoes by PCR. We shipped 4 of those samples to the CDC for sequencing as described previously; 36 samples did not amplify using An. stephensi, An. gambiae, or An. funestus PCR protocols and are the subject of further investigation. We did not conduct morphologic identification on those samples before DNA extraction; the samples will be sequenced to determine species at a later date. No adult mosquitoes were collected in light traps. In summary, of the 59 mosquito samples tested by PCR from collections in Marsabit, 23 were confirmed to be An. stephensi mosquitoes.

Of the 9 sites monitored in Lodwar town during November 8–December 22, 2022, two had only culicine larvae and 7 had Anopheles larvae. A total of 1,415 larvae were collected and screened by PCR; 1,218 were collected from river pans, 50 from cisterns, 147 from drainage ditches, and the remaining from other sources. Two pooled extracts from river pans on the Turkwel River screened positive for An. stephensi. We separated, extracted, and retested 5 larvae; 5 were confirmed to be An. stephensi mosquitoes.

Sequencing

The sequences for 3 of the 4 adult samples matched CO1 isolates from GenBank and were confirmed as An. stephensi mosquitoes (Figure 4). One sample failed to amplify, possibly because of DNA degradation (Table 3). BLAST searches using default parameters for isolates 2 and 3 matched to An. stephensi sequences with 100% identity to the hap 10 5.8S ribosomal RNA gene, ITS2; isolate 1 had 99.4% identity to the same gene but 100% identity to the An. stephensi isolate 141 steph 5.8S ribosomal RNA gene, ITS2. However, when we focused on the CO1 genes in BLAST searches, we found that isolates 1 and 2 exhibited a striking similarity of 100% (isolate 1) and 99.7% (isolate 2) to An. stephensi isolate SM147. Conversely, isolate 3 displayed a substantial 99% identity to An. stephensi isolate ANST15 (Table 3).

In-depth phylogenetic analyses of the CO1 sequences from Kenya isolates 1 and 2 demonstrated a close relationship with sequences from Ethiopia isolates; isolate 3 exhibited a close association with sequences from India (Figure 5). On the other hand, phylogenetic analysis of sequenced isolates with other isolates of ITS2 for An. stephensi available in GenBank demonstrated that the isolates from Marsabit and Turkana matched quite closely; however, because ITS2 is a nuclear marker, it was not used to infer relatedness. The isolates closely matched the Iraq, India, Yemen, and Nigeria isolates (Figure 6). The An. stephensi sequences from this study have been uploaded to GenBank (accession nos. OQ275144, OQ275145, and OQ275146 [ITS2 sequences from Marsabit]; OQ878216, OQ878217, and OQ878218 [sequences from Turkana]; and OR607949, OR607950, and OR607951 [CO1 sequences from Marsabit]).

We report collection and detection of An. stephensi mosquitoes from Marsabit and Turkana Counties in northern Kenya. From the samples collected, we used multiple methods for identification, including morphologic keys, standard ITS2 and CO1 PCR, and Sanger and next-generation sequencing. Molecular methods were instrumental in confirming the presence of An. stephensi mosquitoes. The mosquitoes were collected as larvae. The lack of adult mosquitoes found in the light traps indicates the need for studies to characterize adult vector bionomics and behavior to elucidate how they contribute to transmitting malaria and to design appropriate tools for surveillance of adult An. stephensi mosquitoes.

Reports from other sites have documented the difficulty of trapping adult mosquitoes (7). The bionomics and behavior of this vector in its recent invasive geographic foci are poorly understood; the only available detailed descriptions are from Asia (4,13,22). However, reports from Ethiopia on this vector have indicated that crepuscular biting behaviors and resting outside houses could translate to reduced efficacy of core vector-control interventions, insecticide-treated bed nets, and indoor residual spraying, indicating the importance of accurate parameters (8,13,23). In addition, the effectiveness of any insecticide-based control method will depend on the insecticide resistance of the An. stephensi mosquito; insecticide-resistance surveys are needed (8,23).

On the basis of the phylogenetic analysis of ITS2, the Kenya An. stephensi isolates from Turkana and Marsabit matched one another closely, but because we only conducted CO1 analysis of mosquitoes collected from Marsabit, data were insufficient to infer relatedness. The isolates also matched closely with isolates from India, Iraq, Yemen, Iran, and Nigeria but were more distant from the isolates from Ethiopia. However, phylogenetic analysis of CO1 demonstrated 2 of the Marsabit samples matched closely with isolates from Ethiopia, meaning they are likely related and suggesting a southward invasion of An. stephensi mosquitoes from Ethiopia. This finding asserts the importance of sequencing CO1 amplicons to infer common phylogenetic origins of An. stephensi species. Additional population genetics studies using whole-genome sequencing approaches to describe these clades are needed, along with intensive surveillance to describe their bionomics and behavior.

Our findings also suggest potential introduction routes; An. stephensi mosquitoes were found along highways connecting Kenya to Ethiopia and South Sudan, highlighting the need for increased surveillance along major transportation routes, ideally targeting such areas as truck stops and resting sites, weighbridges, and borders. Future work should include phylogenetic analysis of CO1 isolates of An. stephensi mosquitoes to understand their origin and spread. Further, tracking parasites that cause malaria cases around the areas where An. stephensi mosquitoes have been introduced will be key given that the species is an efficient vector of both P. falciparum and P. vivax.

Because of rapid, often unplanned, urbanizing in Africa, many urban centers have poor refuse disposal and drainage systems that are potential larval habitats of An. stephensi mosquitoes. In addition, because of inadequate social amenities in informal urban settlements, most inhabitants rely on water storage containers for domestic use. Such containers can thus become major breeding habitats for An. stephensi mosquitoes, further compounding the problem of malaria transmission in urbanized areas (2,10). A recent report described the role of construction in urban areas in Ethiopia in propagating An. stephensi larval breeding through uncovered cisterns, plastic containers, and pits dug out for brick manufacturing (S. Yared et al., unpub. data, https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2023.05.23.541906v1). In this study, An. stephensi larvae were collected in riverbeds, which is notable because An. stephensi mosquitoes are thought to confine themselves to habitats similar to those of Aedes spp. mosquitoes. That level of plasticity in colonizing larval habitats demonstrates the potential for this species to invade rural and urban areas alike. In addition, climate change, which creates suitable climatic conditions for mosquito breeding, also means the potential for the spread and establishment of An. stephensi mosquitoes in cities in Africa is great.

When An. stephensi mosquitoes were introduced into Djibouti (2), the country was at the preelimination stage for malaria but then spiked to nearly 3,000 reported malaria cases in 2013, just 1 year after the mosquito was first reported. In 2019, just 6 years later, Djibouti reported 49,402 malaria cases (24). Modeling of the potential effects of An. stephensi mosquito establishment in Ethiopia predicts a surge in P. falciparum cases by 50% overall if no additional interventions are put in place; areas of lowest transmission (≈0.1%) are forecast to be affected the most (8). Similar models need to be conducted in all areas that are newly invaded to predict the spread and effects of the vector and to learn more about the potential effects of additional interventions.

The breeding habitats of An. stephensi mosquitoes are similar to those of Ae. aegypti mosquitoes, but the resting and biting behavior of adult An. stephensi mosquitoes in their invasive range in Africa is less well understood (1,25). Evidence of outdoor, crepuscular feeding by this species suggests it might be less affected by insecticide-treated bed nets or indoor residual spraying as a vector-control intervention. Furthermore, An. stephensi mosquitoes in Ethiopia were reported to be highly resistant to pyrethroids, carbamates, and organophosphates (13). Those traits indicate that alternative vector-control measures and non–vector-control measures might be needed to address the threat of this invasive mosquito. As the national malaria control program develops a vector-control strategy, integrated vector management approaches offer advantages because of the potential benefit of targeting additional vectors on the basis of World Health Organization guidance (26,27), particularly because of the poor understanding of this vector’s behavior when it colonizes new areas. Deploying an integrated approach provides opportunities to target Ae. aegypti and An. stephensi vectors for surveillance and control using similar interventions, which could optimize resource allocation and use in the resource-limited settings where An. stephensi mosquitoes are currently being reported. Managing larval sources, including by applying larvicides, reducing larval sources, and modifying the environment to make it less conducive to productive mosquito aquatic stages, has been pointed out as a potential strategy for targeting An. stephensi mosquitoes, given their tendency to breed in human-made containers in urban areas (3,13,23,28; S Yared et al., unpub. data). Other potential vector control tools, including those currently under evaluation, include spatial repellents (29), attractive targeted sugar baits (30), endectocides (31), insecticide-treated clothing (32), and genetically modified mosquitoes (33). Given the mosquito’s outdoor, early-evening biting behaviors, its resistance to multiple insecticides, and the threat it poses to malaria control efforts, these alternative vector-control approaches might be necessary to sustain gains made against malaria over the past 2 decades.

The first limitation of our study is that samples were collected over a short time frame in a limited number of sites; in Turkana County, we conducted 4 collections in 2 months at 9 sites, and in Marsabit County, collections were performed at 6 sites over 2 months. Therefore, the temporal and spatial extent of the An. stephensi mosquito is still largely unknown and is likely more widespread than this initial report would suggest. Furthermore, only larval samples of An. stephensi mosquitoes could be collected, pointing to gaps in our understanding of adult behavior and optimal adult sampling tools and methods. Collection of other Anopheles species was likely lacking because collections occurred in the dry season, which also demonstrates the potential for An. stephensi mosquitoes to sustain transmission in dry seasons, as has been predicted elsewhere (34). Last, 75% of samples collected in Marsabit could not be amplified by any of the species identification PCR protocols available in the KEMRI laboratory and will be sequenced once the budget is available. Amplifying those samples is a critical first step in combating this emerging threat. Expanding surveillance activities to mitigate the spread of An. stephensi mosquitoes will be key, as will learning more about how this invasive vector is related to recent malaria outbreaks in both counties.

In conclusion, we confirm the presence of An. stephensi mosquitoes in northern Kenya, which points to the urgent need to reexamine and expand vector surveillance and control efforts to include this vector. This mosquito vector is likely to sustain and possibly increase malaria transmission in northern Kenya and spread further southward to highly populated urban areas and existing malaria-endemic counties, further compounding the problem of malaria control in the country. Our findings emphasize the need for heightened and tailored surveillance to elucidate the scope of this invasive vector’s spread, to initiate research on the bionomics of the vector, and to advise on targeted control using existing interventions, including those currently under trial.

Dr. Ochomo is senior research scientist and head of the entomology department at the KEMRI Centre for Global Health Research in Kisumu, Kenya. His primary research interests are laboratory, semifield, and large-scale randomized control trials of novel vector-control products and surveillance, including bionomics, ecology, and vector genomics.

Acknowledgments

We thank Paul Omondi Osodo, Stephen Okeyo, George Marube, and James Opalla, who conducted the survey leading to the discovery of An. stephensi in Marsabit; Ian Mabiria and Blantine Akinyi, who supported the molecular identification process; and Richard Amito, who supported the rearing of the collected larvae. We thank James Kiarie, who helped with the data computation and development of the maps. We are grateful to Tabitha Chepkwony and Mark Amunga, who conducted PCR of the Turkana samples, as well as Leonard Ndwiga, Brian Bartilol and Jonathan Karisa, who participated in the assay optimization and sequencing of the same samples.

This work was supported by funding from NIH_NIAID through the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine (LSTM) and Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation Grant #INV-024969 to KEMRI and GF NFM III to the DNMP. This manuscript is published with the permission of the Director-General of the Kenya Medical Research Institute.

E.O.O., E.O., L.N., E.J., J.D.O., D.M.M., L. Kamau, J.E.G., M.S., D.W., J.M., M. Maia, C.C., A. Omar, W.P.O., A. Obala, C.M., and L. Kariuki conceptualized the study, analyzed data, and assisted in drafting the manuscript. S.M., B.A., B.O., M. Muchoki, D.O., C.R., M.R., and L.A. designed the study; conducted sample collection and processing, data collection, and data analysis; and assisted in drafting the manuscript. All authors read and approved this manuscript.

This article was published as a preprint at https://www.researchsquare.com/article/rs-2498485/v1.

References

- Mnzava A, Monroe AC, Okumu F. Anopheles stephensi in Africa requires a more integrated response. Malar J. 2022;21:156. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Faulde MK, Rueda LM, Khaireh BA. First record of the Asian malaria vector Anopheles stephensi and its possible role in the resurgence of malaria in Djibouti, Horn of Africa. Acta Trop. 2014;139:39–43. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Ahmed A, Khogali R, Elnour MB, Nakao R, Salim B. Emergence of the invasive malaria vector Anopheles stephensi in Khartoum State, Central Sudan. Parasit Vectors. 2021;14:511. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- World Health Organization. WHO initiative to stop the spread of Anopheles stephensi in Africa. Geneva: The Organization; 2022.

- Carter TE, Yared S, Gebresilassie A, Bonnell V, Damodaran L, Lopez K, et al. First detection of Anopheles stephensi Liston, 1901 (Diptera: culicidae) in Ethiopia using molecular and morphological approaches. Acta Trop. 2018;188:180–6. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- World Health Organization. WHO initiative to stop the spread of Anopheles stephensi in Africa—2023 update. Geneva: The Organization; 2023.

- Tadesse FG, Ashine T, Teka H, Esayas E, Messenger LA, Chali W, et al. Anopheles stephensi Mosquitoes as Vectors of Plasmodium vivax and falciparum, Horn of Africa, 2019. Emerg Infect Dis. 2021;27:603–7. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Hamlet A, Dengela D, Tongren JE, Tadesse FG, Bousema T, Sinka M, et al. The potential impact of Anopheles stephensi establishment on the transmission of Plasmodium falciparum in Ethiopia and prospective control measures. BMC Med. 2022;20:135. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- de Santi VP, Khaireh BA, Chiniard T, Pradines B, Taudon N, Larréché S, et al. Role of Anopheles stephensi mosquitoes in malaria outbreak, Djibouti, 2019. Emerg Infect Dis. 2021;27:1697–700. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Sinka ME, Pironon S, Massey NC, Longbottom J, Hemingway J, Moyes CL, et al. A new malaria vector in Africa: Predicting the expansion range of Anopheles stephensi and identifying the urban populations at risk. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020;117:24900–8. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Collins FH, Mendez MA, Rasmussen MO, Mehaffey PC, Besansky NJ, Finnerty V. A ribosomal RNA gene probe differentiates member species of the Anopheles gambiae complex. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1987;37:37–41. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Singh OP, Kaur T, Sharma G, Kona MP, Mishra S, Kapoor N, et al. Molecular tools for early detection of invasive malaria vector Anopheles stephensi mosquitoes. Emerg Infect Dis. 2023;29:36–44. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Balkew M, Mumba P, Dengela D, Yohannes G, Getachew D, Yared S, et al. Geographical distribution of Anopheles stephensi in eastern Ethiopia. Parasit Vectors. 2020;13:35. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Coetzee M. Key to the females of Afrotropical Anopheles mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae). Malar J. 2020;19:70. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Folmer O, Black M, Hoeh W, Lutz R, Vrijenhoek R. DNA primers for amplification of mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase subunit I from diverse metazoan invertebrates. Mol Mar Biol Biotechnol. 1994;3:294–9.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Bankevich A, Nurk S, Antipov D, Gurevich AA, Dvorkin M, Kulikov AS, et al. SPAdes: a new genome assembly algorithm and its applications to single-cell sequencing. J Comput Biol. 2012;19:455–77. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Katoh K, Misawa K, Kuma K, Miyata T. MAFFT: a novel method for rapid multiple sequence alignment based on fast Fourier transform. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:3059–66. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Katoh K, Standley DM. MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: improvements in performance and usability. Mol Biol Evol. 2013;30:772–80. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Minh BQ, Schmidt HA, Chernomor O, Schrempf D, Woodhams MD, von Haeseler A, et al. Corrigendum to: IQ-TREE 2: new models and efficient methods for phylogenetic inference in the genomic era. Mol Biol Evol. 2020;37:2461. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Minh BQ, Schmidt HA, Chernomor O, Schrempf D, Woodhams MD, von Haeseler A, et al. IQ-TREE 2: new models and efficient methods for phylogenetic inference in the genomic era. Mol Biol Evol. 2020;37:1530–4. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Tamura K, Stecher G, Kumar S. MEGA11: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Version 11. Mol Biol Evol. 2021;38:3022–7. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- World Health Organization. Vector alert: Anopheles stephensi invasion and spread: Horn of Africa, the Republic of the Sudan and surrounding geographical areas, and Sri Lanka: information note. Geneva: The Organization; 2019.

- Balkew M, Mumba P, Yohannes G, Abiy E, Getachew D, Yared S, et al. An update on the distribution, bionomics, and insecticide susceptibility of Anopheles stephensi in Ethiopia, 2018-2020. Malar J. 2021;20:263. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Seyfarth M, Khaireh BA, Abdi AA, Bouh SM, Faulde MK. Five years following first detection of Anopheles stephensi (Diptera: Culicidae) in Djibouti, Horn of Africa: populations established-malaria emerging. Parasitol Res. 2019;118:725–32. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Takken W, Lindsay S. Increased threat of urban malaria from Anopheles stephensi mosquitoes, Africa. Emerg Infect Dis. 2019;25:1431–3. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- World Health Organization. Global vector control response 2017–2030. Geneva: The Organization; 2017.

- World Health Organization. Global framework for the response to malaria in urban areas. Geneva: The Organization; 2022.

- Ahmed A, Irish SR, Zohdy S, Yoshimizu M, Tadesse FG. Strategies for conducting Anopheles stephensi surveys in non-endemic areas. Acta Trop. 2022;236:

106671 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Achee NL, Perkins TA, Moore SM, Liu F, Sagara I, Van Hulle S, et al. Spatial repellents: The current roadmap to global recommendation of spatial repellents for public health use. Curr Res Parasitol Vector Borne Dis. 2022;3:

100107 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Attractive Targeted Sugar Bait Phase IIITG; Attractive Targeted Sugar Bait Phase III Trial Group. Attractive targeted sugar bait phase III trials in Kenya, Mali, and Zambia. Trials. 2022;23:640. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Billingsley P, Binka F, Chaccour C, Foy B, Gold S, Gonzalez-Silva M, et al.; The Ivermectin Roadmappers. A roadmap for the development of ivermectin as a complementary malaria vector control tool. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2020;102(2s):3–24. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Banks SD, Murray N, Wilder-Smith A, Logan JG. Insecticide-treated clothes for the control of vector-borne diseases: a review on effectiveness and safety. Med Vet Entomol. 2014;28(Suppl 1):14–25. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Schairer CE, Najera J, James AA, Akbari OS, Bloss CS. Oxitec and MosquitoMate in the United States: lessons for the future of gene drive mosquito control. Pathog Glob Health. 2021;115:365–76. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Whittaker C, Hamlet A, Sherrard-Smith E, Winskill P, Cuomo-Dannenburg G, Walker PGT, et al. Seasonal dynamics of Anopheles stephensi and its implications for mosquito detection and emergent malaria control in the Horn of Africa. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2023;120:

e2216142120 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

Figures

Tables

Cite This ArticleOriginal Publication Date: November 15, 2023

Table of Contents – Volume 29, Number 12—December 2023

| EID Search Options |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Please use the form below to submit correspondence to the authors or contact them at the following address:

Eric Ochomo, Kenya Medical Research Institute—Center for Global Health Research, Kisian Campus, Off Kisumu Busia Rd, Kisumu, Kenya

Top