Volume 30, Number 4—April 2024

Research

Emergence of Poultry-Associated Human Salmonella enterica Serovar Abortusovis Infections, New South Wales, Australia

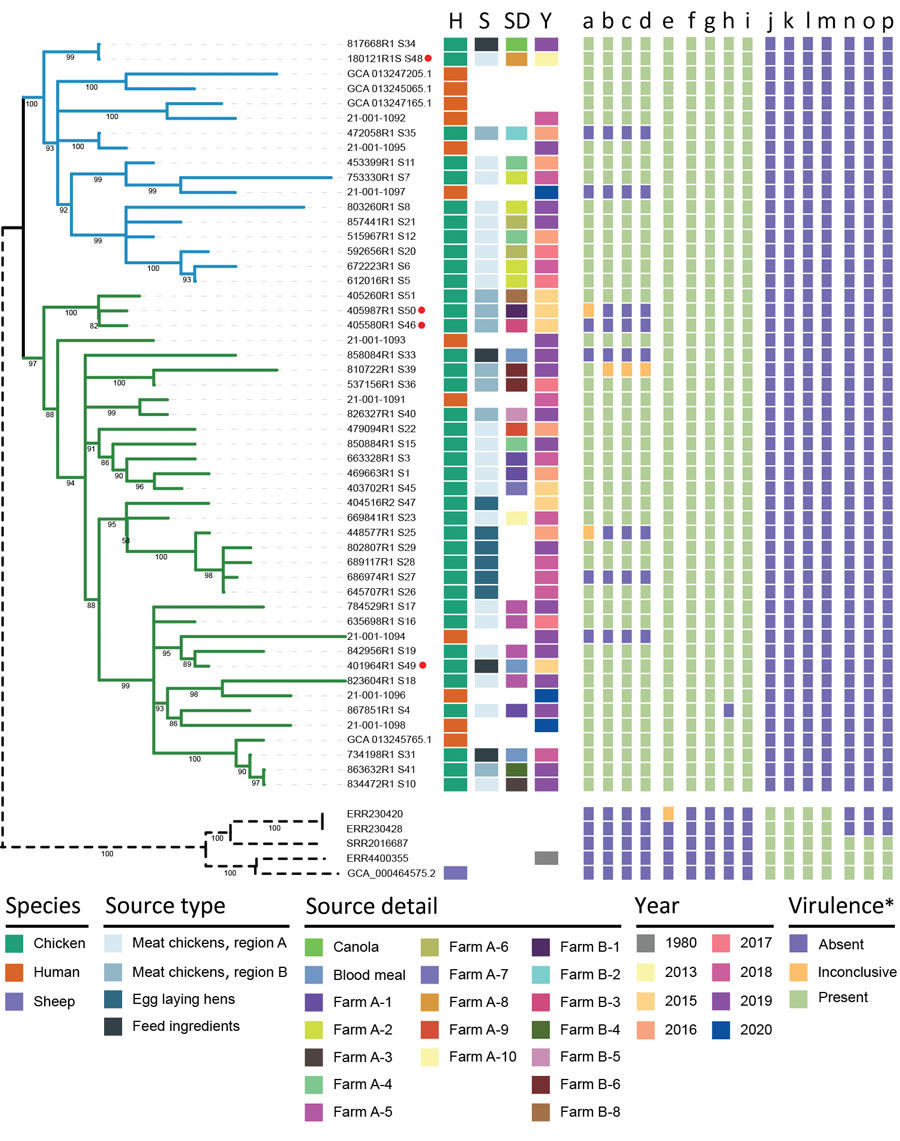

Figure 2

Figure 2. Phylogenetic relationships of isolates and associated metadata in a study of the emergence of poultry-associated human Salmonella enterica serovar Abortusovis infections, New South Wales, Australia. A maximum-likelihood phylogeny of all 56 isolates including subclade annotation and relevant metadata. Branches colors indicate subclades 1 (blue) and 2 (green) and bootstrap support values are indicated at tree nodes. Branch lengths for 5 international isolates were shortened for clarity (dashed lines). Red dots indicate complete genomes. Colors in columns indicate host species, source type, source details, year of isolation, and presence or absence of virulence genes. Virulence genes were predicted by using abricate (https://github.com/tseemann/abricate), KMA (23), and VFDB (25): a) pSAbAus; b) yersinia HPI (11 genes); c) ivy; d) cvaA; e) cdtB; f) cfaB; g) stfF; h) hdeB; i) eutEJGHABCLKR; j) astA; k) sodCI; l) ompN; m) hcp1; n) pSLT-like plasmid; o) spv toxin (3 genes); p) Fimbriae klf/fae (6 genes). *Some virulence genes or islands have the same presence and absence pattern in all genes; those data are collapsed into 1 column and the number of genes are indicated in parentheses in the list. Inconclusive gene presence was assigned when only KMA identified the gene and it had <20% of the normalized genome coverage. H, host species; S, source; SD, source details; Y, year.

References

- Jack E. Salmonella Abortus Ovis—an atypical Salmonella. Vet Rec. 1968;82:558.

- Pardon P, Sanchis R, Marly J, Lantier F, Pépin M, Popoff M. [Ovine salmonellosis caused by Salmonella abortus ovis] [in French]. Ann Rech Vet. 1988;19:221–35.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Belloy L, Decrausaz L, Boujon P, Hächler H, Waldvogel AS. Diagnosis by culture and PCR of Salmonella abortusovis infection under clinical conditions in aborting sheep in Switzerland. Vet Microbiol. 2009;138:373–7. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Vodas K, Marinov MF, Shabanov M. [Salmonella abortus ovis carrier state in dogs and rats] [in Bulgarian]. Vet Med Nauki. 1985;22:10–5.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Bacciu D, Falchi G, Spazziani A, Bossi L, Marogna G, Leori GS, et al. Transposition of the heat-stable toxin astA gene into a gifsy-2-related prophage of Salmonella enterica serovar Abortusovis. J Bacteriol. 2004;186:4568–74. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Colombo MM, Leori G, Rubino S, Barbato A, Cappuccinelli P. Phenotypic features and molecular characterization of plasmids in Salmonella abortusovis. Microbiology. 1992;138:725–31.

- Uzzau S, Gulig PA, Paglietti B, Leori G, Stocker BA, Rubino S. Role of the Salmonella abortusovis virulence plasmid in the infection of BALB/c mice. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2000;188:15–8. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Habrun B, Listes E, Spicic S, Cvetnic Z, Lukacevic D, Jemersic L, et al. An outbreak of Salmonella Abortusovis abortions in sheep in south Croatia. J Vet Med B Infect Dis Vet Public Health. 2006;53:286–90. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Wirz-Dittus S, Belloy L, Hüssy D, Waldvogel AS, Doherr MG. Seroprevalence survey for Salmonella Abortusovis infection in Swiss sheep flocks. Prev Vet Med. 2010;97:126–30. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Valdezate S, Astorga R, Herrera-León S, Perea A, Usera MA, Huerta B, et al. Epidemiological tracing of Salmonella enterica serotype Abortusovis from Spanish ovine flocks by PFGE fingerprinting. Epidemiol Infect. 2007;135:695–702. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Dionisi AM, Carattoli A, Luzzi I, Magistrali C, Pezzotti G. Molecular genotyping of Salmonella enterica Abortusovis by pulsed field gel electrophoresis. Vet Microbiol. 2006;116:217–23. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Schiaffino A, Beuzón CR, Uzzau S, Leori G, Cappuccinelli P, Casadesús J, et al. Strain typing with IS200 fingerprints in Salmonella abortusovis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:2375–80. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Nikbakht GH, Raffatellu M, Uzzau S, Tadjbakhsh H, Rubino S. IS200 fingerprinting of Salmonella enterica serotype Abortusovis strains isolated in Iran. Epidemiol Infect. 2002;128:333–6. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Australian Government Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry. Animal Health Australia 2009. Canberra (ACT), Australia: The Department; 2010.

- Heuzenroeder MW, Ross IL, Hocking H, Davos D, Young CC, Morgan G. An integrated typing service for the surveillance of Salmonella in chickens. Barton (ACT): Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation, Australian Government; 2013.

- Abraham S, O’Dea M, Sahibzada S, Hewson K, Pavic A, Veltman T, et al. Escherichia coli and Salmonella spp. isolated from Australian meat chickens remain susceptible to critically important antimicrobial agents. PLoS One. 2019;14:

e0224281 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Seemann T. snippy: fast bacterial variant calling from NGS reads, version 3.1 [cited 2020 Apr 19]. https://github.com/tseemann/snippy

- Minh BQ, Schmidt HA, Chernomor O, Schrempf D, Woodhams MD, von Haeseler A, et al. IQ-TREE 2: new models and efficient methods for phylogenetic inference in the genomic era. Mol Biol Evol. 2020;37:1530–4. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Letunic I, Bork P. Interactive tree of life (iTOL) v3: an online tool for the display and annotation of phylogenetic and other trees. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44(W1):

W242-5 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Bouckaert R, Vaughan TG, Barido-Sottani J, Duchêne S, Fourment M, Gavryushkina A, et al. BEAST 2.5: An advanced software platform for Bayesian evolutionary analysis. PLOS Comput Biol. 2019;15:

e1006650 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Page AJ, Cummins CA, Hunt M, Wong VK, Reuter S, Holden MT, et al. Roary: rapid large-scale prokaryote pan genome analysis. Bioinformatics. 2015;31:3691–3. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Brynildsrud O, Bohlin J, Scheffer L, Eldholm V. Rapid scoring of genes in microbial pan-genome-wide association studies with Scoary. Genome Biol. 2016;17:238. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Clausen PTLC, Aarestrup FM, Lund O. Rapid and precise alignment of raw reads against redundant databases with KMA. BMC Bioinformatics. 2018;19:307. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Syberg-Olsen MJ, Garber AI, Keeling PJ, McCutcheon JP, Husnik F. Pseudofinder: detection of pseudogenes in prokaryotic genomes. Mol Biol Evol. 2022;39:msac153.

- Liu B, Zheng D, Jin Q, Chen L, Yang J. VFDB 2019: a comparative pathogenomic platform with an interactive web interface. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47(D1):D687–92. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Carattoli A, Hasman H. PlasmidFinder and in silico pMLST: identification and typing of plasmid replicons in whole-genome sequencing (WGS). Methods Mol Biol. 2020;2075:285–94. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Seemann T. ABRicate, mass screening of contigs for antimicrobial resistance or virulence genes. 1.0.1 [cited 2020 Apr 19]. https://github.com/tseemann/abricate

- Wishart DS, Han S, Saha S, Oler E, Peters H, Grant JR, et al. PHASTEST: faster than PHASTER, better than PHAST. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023;51(W1):W443–50. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Zhang X, Payne M, Lan R. In silico identification of serovar-specific genes for Salmonella serotyping. Front Microbiol. 2019;10:835. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Alikhan NF, Zhou Z, Sergeant MJ, Achtman M. A genomic overview of the population structure of Salmonella. PLoS Genet. 2018;14:

e1007261 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Allison GE, Angeles D, Tran-Dinh N, Verma NK. Complete genomic sequence of SfV, a serotype-converting temperate bacteriophage of Shigella flexneri. J Bacteriol. 2002;184:1974–87. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Zhang X, Payne M, Nguyen T, Kaur S, Lan R. Cluster-specific gene markers enhance Shigella and enteroinvasive Escherichia coli in silico serotyping. Microb Genom. 2021;7:

000704 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Clune T, Beetson S, Besier S, Knowles G, Paskin R, Rawlin G, et al. Ovine abortion and stillbirth investigations in Australia. Aust Vet J. 2020;1:22.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Price SL, Vadyvaloo V, DeMarco JK, Brady A, Gray PA, Kehl-Fie TE, et al. Yersiniabactin contributes to overcoming zinc restriction during Yersinia pestis infection of mammalian and insect hosts. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2021;118:

e2104073118 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Wellawa DH, Allan B, White AP, Köster W. Iron-uptake systems of chicken-associated Salmonella serovars and their role in colonizing the avian host. Microorganisms. 2020;8:1203. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Schubert S, Picard B, Gouriou S, Heesemann J, Denamur E. Yersinia high-pathogenicity island contributes to virulence in Escherichia coli causing extraintestinal infections. Infect Immun. 2002;70:5335–7. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Liu D, Yang Y, Gu J, Tuo H, Li P, Xie X, et al. The Yersinia high-pathogenicity island (HPI) carried by a new integrative and conjugative element (ICE) in a multidrug-resistant and hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae strain SCsl1. Vet Microbiol. 2019;239:

108481 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Miller RA, Wiedmann M. The cytolethal distending toxin produced by nontyphoidal Salmonella serotypes Javiana, Montevideo, Oranienburg, and Mississippi induces DNA damage in a manner similar to that of serotype Typhi. MBio. 2016;7:e02109–16. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Joerger RD, Choi S. Contribution of the hdeB-like gene (SEN1493) to survival of Salmonella enterica enteritidis Nal(R) at pH 2. Foodborne Pathog Dis. 2015;12:353–9. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Deckers D, Vanlint D, Callewaert L, Aertsen A, Michiels CW. Role of the lysozyme inhibitor Ivy in growth or survival of Escherichia coli and Pseudomonas aeruginosa bacteria in hen egg white and in human saliva and breast milk. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2008;74:4434–9. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Thiennimitr P, Winter SE, Winter MG, Xavier MN, Tolstikov V, Huseby DL, et al. Intestinal inflammation allows Salmonella to use ethanolamine to compete with the microbiota. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:17480–5. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Anderson CJ, Clark DE, Adli M, Kendall MM. Ethanolamine signaling promotes Salmonella niche recognition and adaptation during infection. PLoS Pathog. 2015;11:

e1005278 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Harris JB, Baresch-Bernal A, Rollins SM, Alam A, LaRocque RC, Bikowski M, et al. Identification of in vivo-induced bacterial protein antigens during human infection with Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi. Infect Immun. 2006;74:5161–8. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Harvey PC, Watson M, Hulme S, Jones MA, Lovell M, Berchieri A Jr, et al. Salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium colonizing the lumen of the chicken intestine grows slowly and upregulates a unique set of virulence and metabolism genes. Infect Immun. 2011;79:4105–21. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Hoelzer K, Moreno Switt AI, Wiedmann M. Animal contact as a source of human non-typhoidal salmonellosis. Vet Res (Faisalabad). 2011;42:34. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Sabbagh SC, Lepage C, McClelland M, Daigle F. Selection of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi genes involved during interaction with human macrophages by screening of a transposon mutant library. PLoS One. 2012;7:

e36643 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Sana TG, Flaugnatti N, Lugo KA, Lam LH, Jacobson A, Baylot V, et al. Salmonella Typhimurium utilizes a T6SS-mediated antibacterial weapon to establish in the host gut. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113:E5044–51. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Langridge GC, Fookes M, Connor TR, Feltwell T, Feasey N, Parsons BN, et al. Patterns of genome evolution that have accompanied host adaptation in Salmonella. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112:863–8. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- AbuOun M, Jones H, Stubberfield E, Gilson D, Shaw LP, Hubbard ATM, et al.; On Behalf Of The Rehab Consortium. A genomic epidemiological study shows that prevalence of antimicrobial resistance in Enterobacterales is associated with the livestock host, as well as antimicrobial usage. Microb Genom. 2021;7:10–2. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- McLure A, Shadbolt C, Desmarchelier PM, Kirk MD, Glass K. Source attribution of salmonellosis by time and geography in New South Wales, Australia. BMC Infect Dis. 2022;22:14. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar