Volume 30, Number 5—May 2024

Dispatch

Toxoplasma gondii Infections and Associated Factors in Female Children and Adolescents, Germany

Abstract

In a representative sample of female children and adolescents in Germany, Toxoplasma gondii seroprevalence was 6.3% (95% CI 4.7%–8.0%). With each year of life, the chance of being seropositive increased by 1.2, indicating a strong force of infection. Social status and municipality size were found to be associated with seropositivity.

Toxoplasmosis, caused by the protozoan parasite Toxoplasma gondii, is the most common parasitic foodborne disease in Germany. The seroprevalence in adults is exceptionally high (50%) compared with other countries (1). After infection via either undercooked meat from infected animals (pathway 1) or uptake of infectious oocysts shed by infected cats (pathway 2), T. gondii persists lifelong in infected persons, posing a risk for reactivation of latent infections (2). The proportion of pathways 1 and 2 leading to infection is largely unknown. We previously argued that in Germany, eating habits like consumption of raw pork products are likely responsible for the high seroprevalence (1). Infections in immune-competent persons remain largely asymptomatic or cause only mild, influenza-like symptoms. However, severe disease manifestations can occur, including ocular toxoplasmosis with sequalae, severe and often fatal consequences in immunocompromised persons, and congenital toxoplasmosis (2).

Worldwide, the World Health Organization (WHO) considered the burden of disease from toxoplasmosis to be high. Nevertheless, routine disease and pathogen surveillance is inadequate, so the incidence of human infection and parasite occurrence in animals and food is underestimated (3). In Germany, T. gondii screening during pregnancy to detect and treat primary infection, which could prevent parasite transmission to the unborn, is not covered by the statutory health insurance. Ongoing discussions to reevaluate this policy demand data specifically assessing risk estimates for women of reproductive age.

In adults, age, dietary habits, and region of residence are associated with seroprevalence (1). Comparable analyses for children and adolescents are missing but are needed to estimate the public health problem and to suggest countermeasures. To provide such baseline data, this study aimed to estimate seroprevalence and to determine associated factors of T. gondii infections in female children and adolescents in Germany. The Hannover Medical School ethics committee approved the study (4).

The second wave of the nationwide German Health Interview and Examination Survey for Children and Adolescents (KiGGS Wave 2) was conducted as a 2-stage sampling survey during 2014‒2017 in 167 representative sample points in Germany (4). Serum specimens of participants 3 ‒17 years of age were tested for the presence of T. gondii IgG using a highly sensitive and specific commercial enzyme linked fluorescence assay (ELFA), as described previously (1,5).

We determined overall and stratified seroprevalence. We used data from standardized interviews to assess factors associated with seropositivity. On the basis of our previous serosurvey results in adults (1), we tested potential associations between seropositivity and vegetarianism, residence (eastern or western Germany), municipality size, and socioeconomic status. We identified minimal adjustment sets for multivariable logistic regression models by using directed acyclic graphs (Appendix). We determined adjusted odds ratios (aOR) for each exposure variable with 95% CIs. We used sampling weights for all statistical analyses accounting for the study design. In addition, we calculated survey weights based on age, sex, residence, nationality, and education to correct for deviations from national population statistics.

We included 1,453 girls and adolescents (mean age 10.3 years) in the analyses. Of those, 1,359 tested negative and 94 tested positive for T. gondii‒specific IgG. We estimated overall weighted seroprevalence at 6.3% (95% CI 4.7%–8.0%) (Table).

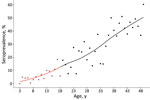

With each year of life, the chance of being seropositive increased significantly, by 1.2 (95% CI 1.1–1.3). When we combined the data from the girls with those of female adults, seroprevalence steadily increased with age (Figure 1). This increase is a result of cumulative seropositivity because T. gondii infection is persistent and shows little seroreversion.

Girls living in families with low socioeconomic status (SES) showed the highest prevalence (10.8%, 95% CI 4.7%–16.9%). Their chance of being seropositive is 2.7 (95% CI 1.3–5.9) times higher than that of girls with middle SES. Low social status is often found to be associated with various disease risks, which may be a result of lower health literacy and reduced options to avoid health-related risks (4).

The seroprevalence among girls living in rural areas (<5,000 inhabitants) was significantly higher than seroprevalence for girls living in small towns (5,000–<20,000 inhabitants) (aOR 2.6, 95% CI 1.1–5.7). Similarly, girls living in urban areas (>100,000 inhabitants) were also 2.2 (95% CI 1.1–4.4) times more likely to be seropositive than those living in small towns. Greater exposure to natural habitats, including sand and soil contaminated due to free-roaming cats (6), as well as cats and children using the same limited spaces (e.g., sandboxes) (7), might explain the respective higher risks of infection. We did not observe any regional distribution patterns (e.g., differences between eastern and western Germany) (Figure 2).

Overall, 9.3% of the participants reported being vegetarian; of those, 6.4% (95% CI 4.6%–8.2%) were seropositive (aOR 1.3, 95% CI 0.5–3.3). This result is not significantly different from results for nonvegetarians and is consistent with other studies (8–10). Diet appeared to have less effect on the risk for infection in children and adolescents than in adults. This finding may indicate that the relevance of the 2 transmission pathways differs significantly between age groups, and more environmentally associated infections occur in children and adolescents. Alternatively, risk factors associated with transmission pathway 1 may have shifted over time, for example, from improvements in the production and preparation of meat. However, more detailed information on the type (raw or undercooked) and quantity of meat consumed would have been beneficial but were not available in our dataset.

Overall, 6 of every 100 girls in Germany become infected with T. gondii during the first 18 years of life, corresponding to ≈340,504 total infections in this population group. Internationally comparable studies are limited. Seroprevalence estimates vary worldwide, from <10% to >60% for girls and 10%–80% for adults (11,12). Toxoplasmosis causes a higher infection pressure for girls and young women in Germany than in countries with similar socioeconomic conditions (11,13). In the United States, for example, the seroprevalence is significantly lower in age groups 6‒11 years (0.9%, 95% CI 0.5%–1.5%) and 12‒19 years (3.1%, 95% CI 2.0%–4.6%) (11).

Independent risk factors identified in our study were age, low social status, and growing up in rural or urban areas. Those factors have also been associated with seropositivity in children and adolescents in other countries (12,14). Further risk factors include contact with cats (12,14,15), contact with soil or sand (8,9,15), and consumption of unwashed vegetables (8). Growing up on a farm or keeping farm animals was also associated with increased seroconversions (8,10). Regular handwashing showed protective effects (9,15).

Our data may be helpful as an empirical basis for prevention guidelines. Implementing screening of pregnant women is one possibility and should be reevaluated using current data. Furthermore, our results indicate that meat consumption does not appear to be a driving force in children and adolescents, which calls for different prevention strategies in this population than in adults (Appendix). However, our serosurvey is cross-sectional and represents the cumulated lifetime risk for infection. Therefore, misclassification of exposures (e.g., participants reported vegetarianism but consumed raw meat earlier in life) and unmeasured confounding is likely. Thus, our data are not appropriate for establishing causal relationships. Future studies should use longitudinal data containing detailed information on exposures and time of infection to disentangle different transmission pathways. The ultimate goal is efficient primary prevention of T. gondii infections; the goal requires integrating the fields of veterinary, human, and environmental medicine in a One Health approach.

Ms. Giese is an epidemiologist at the Robert Koch Institute with strong interest in gastrointestinal infections, zoonoses and tropical infections.

Acknowledgments

We thank Daniela Heckmann, Petra Gosten-Heinrich, Elisabeth Kamal, Sandra Klein, Gudrun Kliem, Ilka McCormick-Smith, and Elke Radam for expert technical help.

This work was supported by the Robert Koch Institute, Berlin, Germany.

References

- Wilking H, Thamm M, Stark K, Aebischer T, Seeber F. Prevalence, incidence estimations, and risk factors of Toxoplasma gondii infection in Germany: a representative, cross-sectional, serological study. Sci Rep. 2016;6:22551. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Pleyer U, Gross U, Schlüter D, Wilking H, Seeber F. Toxoplasmosis in Germany. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2019;116:435–44.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Koutsoumanis K, Allende A, Alvarez-Ordóñez A, Bolton D, Bover-Cid S, Chemaly M, et al.; EFSA Panel on Biological Hazards (BIOHAZ). Public health risks associated with food-borne parasites. EFSA J. 2018;16:

e05495 .PubMedGoogle Scholar - Lampert T, Hoebel J, Kuntz B, Müters S, Kroll LE. Socioeconomic status and subjective social status measurement in KiGGS Wave 2. J Health Monit. 2018;3:108–25.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Murat JB, Dard C, Fricker Hidalgo H, Dardé ML, Brenier-Pinchart MP, Pelloux H. Comparison of the Vidas system and two recent fully automated assays for diagnosis and follow-up of toxoplasmosis in pregnant women and newborns. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2013;20:1203–12. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Candela MG, Fanelli A, Carvalho J, Serrano E, Domenech G, Alonso F, et al. Urban landscape and infection risk in free-roaming cats. Zoonoses Public Health. 2022;69:295–311. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Pacheco-Ortega GA, Chan-Pérez JI, Ortega-Pacheco A, Guzmán-Marín E, Edwards M, Brown MA, et al. Screening of zoonotic parasites in playground sandboxes of public parks from subtropical Mexico. J Parasitol Res. 2019;2019:

7409076 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Hofhuis A, van Pelt W, van Duynhoven YTHP, Nijhuis CDM, Mollema L, van der Klis FRM, et al. Decreased prevalence and age-specific risk factors for Toxoplasma gondii IgG antibodies in The Netherlands between 1995/1996 and 2006/2007. Epidemiol Infect. 2011;139:530–8. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Sharif M, Daryani A, Barzegar G, Nasrolahei M. A seroepidemiological survey for toxoplasmosis among schoolchildren of Sari, Northern Iran. Trop Biomed. 2010;27:220–5.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Nash JQ, Chissel S, Jones J, Warburton F, Verlander NQ. Risk factors for toxoplasmosis in pregnant women in Kent, United Kingdom. Epidemiol Infect. 2005;133:475–83. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Jones JL, Kruszon-Moran D, Elder S, Rivera HN, Press C, Montoya JG, et al. Toxoplasma gondii Infection in the United States, 2011-2014. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2018;98:551–7. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Fan CK, Lee LW, Liao CW, Huang YC, Lee YL, Chang YT, et al. Toxoplasma gondii infection: relationship between seroprevalence and risk factors among primary schoolchildren in the capital areas of Democratic Republic of São Tomé and Príncipe, West Africa. Parasit Vectors. 2012;5:141. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Liassides M, Christodoulou V, Moschandreas J, Karagiannis C, Mitis G, Koliou M, et al. Toxoplasmosis in female high school students, pregnant women and ruminants in Cyprus. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2016;110:359–66. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Cabral Monica T, Evers F, de Souza Lima Nino B, Pinto-Ferreira F, Breganó JW, Ragassi Urbano M, et al. Socioeconomic factors associated with infection by Toxoplasma gondii and Toxocara canis in children. Transbound Emerg Dis. 2022;69:1589–95. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Wang S, Yao Z, Li H, Li P, Wang D, Zhang H, et al. Seroprevalence and risk factors of Toxoplasma gondii infection in primary school children in Henan province, central China. Parasite. 2020;27:23. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

Figures

Table

Cite This ArticleOriginal Publication Date: April 10, 2024

1These authors contributed equally to this article.

Table of Contents – Volume 30, Number 5—May 2024

| EID Search Options |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Please use the form below to submit correspondence to the authors or contact them at the following address:

Laura Giese, Robert Koch Institute, Department of Infectious Disease Epidemiology, Seestraße 10, 13353 Berlin, Germany

Top