Volume 31, Number 5—May 2025

Research

Exponential Clonal Expansion of 5-Fluorocytosine–Resistant Candida tropicalis and New Insights into Underlying Molecular Mechanisms

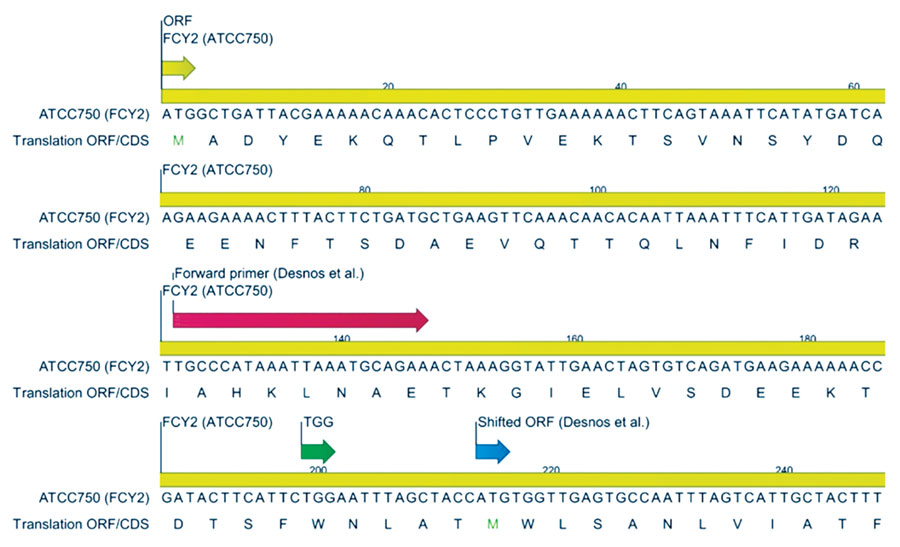

Figure 2

Figure 2. FCY2 sequence encoding the purine-cytosine permease derived from contig 14 of the Candida tropicalis strain ATCC 750 genome assembly, published on the ATCC Genome Portal in 2020. The coding sequence spans positions 2152980–2154500. The ORF is depicted at the top left of the figure; long red arrow illustrates the FCY2 forward primer designed by Desnos-Ollivier et al. (12), and the blue arrow indicates the ORF they used. The green arrow represents the tryptophan codon TGG, which is converted to stop codon TGA in the MYA 3404 genome assembly. CDS, coding sequence; ORF, open reading frame.

References

- Spampinato C, Leonardi D. Candida infections, causes, targets, and resistance mechanisms: traditional and alternative antifungal agents. BioMed Res Int. 2013;2013:

204237 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Pappas PG, Lionakis MS, Arendrup MC, Ostrosky-Zeichner L, Kullberg BJ. Invasive candidiasis. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2018;4:18026. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Risum M, Astvad K, Johansen HK, Schønheyder HC, Rosenvinge F, Knudsen JD, et al. Update 2016–2018 of the nationwide Danish fungaemia surveillance study: epidemiologic changes in a 15-year perspective. J Fungi (Basel). 2021;7:491. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Roilides E, Farmaki E, Evdoridou J, Francesconi A, Kasai M, Filioti J, et al. Candida tropicalis in a neonatal intensive care unit: epidemiologic and molecular analysis of an outbreak of infection with an uncommon neonatal pathogen. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41:735–41. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Spruijtenburg B, De Carolis E, Magri C, Meis JF, Sanguinetti M, de Groot T, et al. Genotyping of Candida tropicalis isolates uncovers nosocomial transmission of two lineages in Italian tertiary care hospital. J Hosp Infect. 2025;155:115–22. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Wang Q, Tang D, Tang K, Guo J, Huang Y, Li C. Multilocus sequence typing reveals clonality of fluconazole-nonsusceptible Candida tropicalis: a study from Wuhan to the global. Front Microbiol. 2020;11:

554249 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Sigera LSM, Denning DW. Flucytosine and its clinical usage. Ther Adv Infect Dis. 2023;10:

20499361231161387 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Longley DB, Harkin DP, Johnston PG. 5-fluorouracil: mechanisms of action and clinical strategies. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3:330–8. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Zhang N, Yin Y, Xu SJ, Chen WS. 5-Fluorouracil: mechanisms of resistance and reversal strategies. Molecules. 2008;13:1551–69. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Law D, Moore CB, Joseph LA, Keaney MGL, Denning DW. High incidence of antifungal drug resistance in Candida tropicalis. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 1996;7:241–5. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Tortorano AM, Rigoni AL, Biraghi E, Prigitano A, Viviani MA; FIMUA-ECMM Candidaemia Study Group. The European Confederation of Medical Mycology (ECMM) survey of candidaemia in Italy: antifungal susceptibility patterns of 261 non-albicans Candida isolates from blood. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2003;52:679–82. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Desnos-Ollivier M, Bretagne S, Bernède C, Robert V, Raoux D, Chachaty E, et al.; Yeasts Group. Clonal population of flucytosine-resistant Candida tropicalis from blood cultures, Paris, France. Emerg Infect Dis. 2008;14:557–65. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Arendrup MC, Arikan-Akdagli S, Jørgensen KM, Barac A, Steinmann J, Toscano C, et al. European candidaemia is characterised by notable differential epidemiology and susceptibility pattern: Results from the ECMM Candida III study. J Infect. 2023;87:428–37. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- European Committee for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST). Susceptibility testing of yeasts. version 7.4. October 2023 [cited 2025 Mar 13]. https://www.eucast.org/astoffungi/methodsinantifungalsusceptibilitytesting/susceptibility_testing_of_yeasts

- Turnidge J, Kahlmeter G, Kronvall G. Statistical characterisation of bacterial wild-type MIC value distributions and the determination of epidemiological cut-off values. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2006;12:418–25. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Wu Y, Zhou H-J, Che J, Li W-G, Bian F-N, Yu S-B, et al. Multilocus microsatellite markers for molecular typing of Candida tropicalis isolates. BMC Microbiol. 2014;14:245. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Guinea J, Arendrup MC, Cantón R, Cantón E, García-Rodríguez J, Gómez A, et al. Genotyping reveals high clonal diversity and widespread genotypes of Candida causing candidemia at distant geographical areas. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2020;10:166. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Chen YN, Lo HJ, Wu CC, Ko HC, Chang TP, Yang YL. Loss of heterozygosity of FCY2 leading to the development of flucytosine resistance in Candida tropicalis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011;55:2506–14. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Chevallier MR, Jund R, Lacroute F. Characterization of cytosine permeation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Bacteriol. 1975;122:629–41. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Chan KK, Wood BMK, Fedorov AA, Fedorov EV, Imker HJ, Amyes TL, et al. Mechanism of the orotidine 5′-monophosphate decarboxylase-catalyzed reaction: evidence for substrate destabilization. Biochemistry. 2009;48:5518–31. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Nygaard P, Saxild HH. Nucleotide metabolism. In: Schaechter M, editor. Encyclopedia of microbiology. 3rd ed. Oxford: Academic Press; 2009. p. 296–307.

- Li G, Li D, Wang T, He S. Pyrimidine biosynthetic enzyme CAD: its function, regulation, and diagnostic potential. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22:10253. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Xu J. Is natural population of Candida tropicalis sexual, parasexual, and/or asexual? Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2021;11:

751676 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

Page created: April 14, 2025

Page updated: April 25, 2025

Page reviewed: April 25, 2025

The conclusions, findings, and opinions expressed by authors contributing to this journal do not necessarily reflect the official position of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, the Public Health Service, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, or the authors' affiliated institutions. Use of trade names is for identification only and does not imply endorsement by any of the groups named above.