Disclaimer: Early release articles are not considered as final versions. Any changes will be reflected in the online version in the month the article is officially released.

Volume 32, Number 2—February 2026

Research Letter

Vesicular Disease Caused by Seneca Valley Virus in Pigs, England, 2022

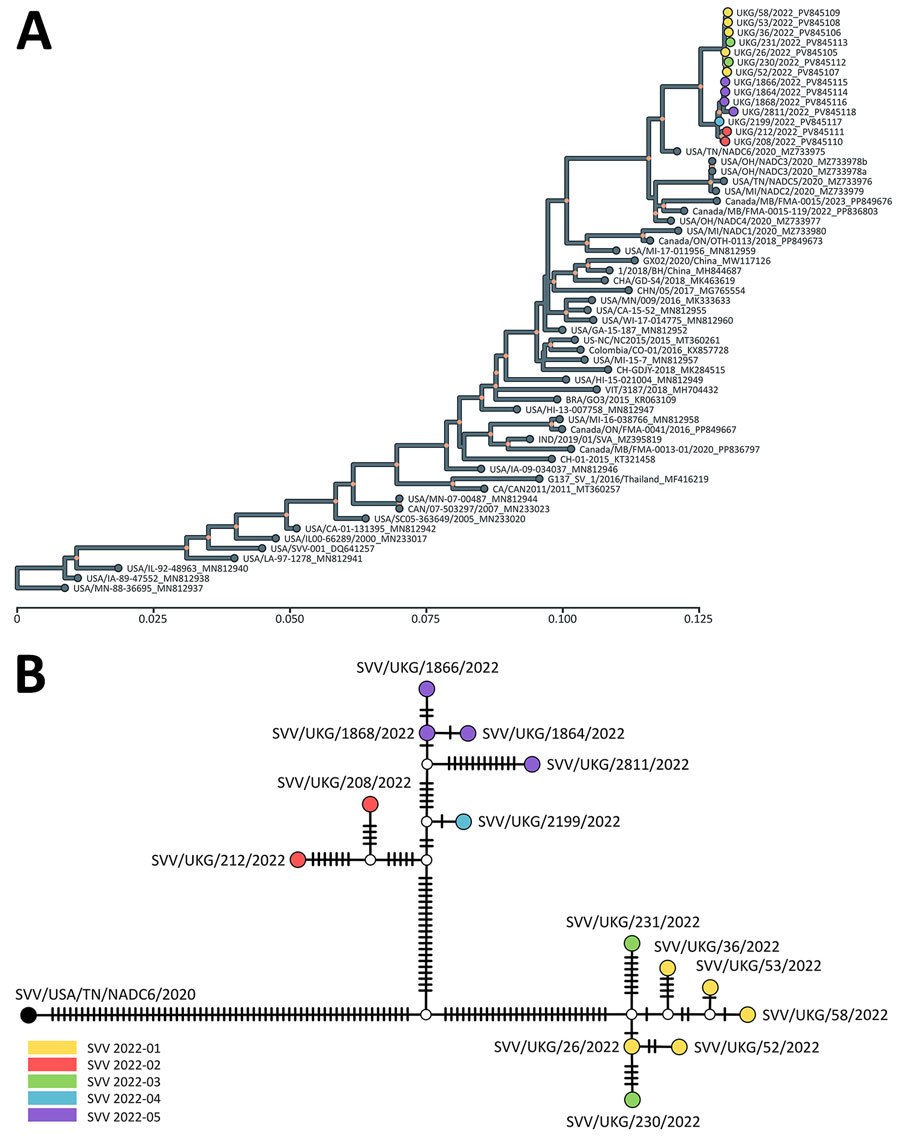

Figure 2

Figure 2. Evolutionary history and genetic relationships of Seneca Valley viruses from study of vesicular disease caused by Seneca Valley virus in pigs, England, 2022. A) Tree represents the evolutionary history of Seneca Valley viruses isolated globally and reconstructed using polyprotein-coding sequences. Maximum-likelihood tree inferred using the Tamura-Nei model (9) and setting a discrete gamma distribution for evolutionary rate differences among sites. Colored tips represent Seneca Valley virus–infected farms during the outbreak in England in 2022. Colored internal nodes represent the percentage of trees in which the associated taxa clustered together on >50%. Evolutionary analyses were conducted in MEGA11 (10). Scale bar indicates nucleotide substitutions per site. B) Genetic relationship of Seneca Valley viruses isolated in England during 2022 based on the full-genome length, as reconstructed by statistical parsimony analysis. Nodes are colored according to farm on which clinical cases were observed; white nodes denote missing unsampled haplotypes. Hatch marks represent single-nucleotide substitutions estimated between the connected nodes.

References

- Pasma T, Davidson S, Shaw SL. Idiopathic vesicular disease in swine in Manitoba. Can Vet J. 2008;49:84–5.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Bennett B, Urzúa-Encina C, Pardo-Roa C, Ariyama N, Lecocq C, Rivera C, et al. First report and genetic characterization of Seneca Valley virus (SVV) in Chile. Transbound Emerg Dis. 2022;69:e3462–8. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Maan S, Batra K, Chaudhary D, Punia M, Kadian V, Joshi VG, et al. Detection and genomic characterization of Senecavirus from Indian pigs. Indian J Anim Res. 2023;57:1344–50.

- Navarro-López R, Perez-De la Rosa JD, Rocha-Martínez MK, Hernández GG, Villarreal-Silva M, Solís-Hernández M, et al. First detection and genetic characterization of Senecavirus A in pigs from Mexico. J Swine Health Prod. 2023;31:289–94. DOIGoogle Scholar

- Reid SM, Grierson SS, Ferris NP, Hutchings GH, Alexandersen S. Evaluation of automated RT-PCR to accelerate the laboratory diagnosis of foot-and-mouth disease virus. J Virol Methods. 2003;107:129–39. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Fowler VL, Ransburgh RH, Poulsen EG, Wadsworth J, King DP, Mioulet V, et al. Development of a novel real-time RT-PCR assay to detect Seneca Valley virus-1 associated with emerging cases of vesicular disease in pigs. J Virol Methods. 2017;239:34–7. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Colenutt C, Brown E, Nelson N, Wadsworth J, Maud J, Adhikari B, et al. Environmental sampling as a low-technology method for surveillance of foot-and-mouth disease virus in an area of endemicity. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2018;84:e00686–18. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Logan G, Freimanis GL, King DJ, Valdazo-González B, Bachanek-Bankowska K, Sanderson ND, et al. A universal protocol to generate consensus level genome sequences for foot-and-mouth disease virus and other positive-sense polyadenylated RNA viruses using the Illumina MiSeq. BMC Genomics. 2014;15:828. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Tamura K, Nei M. Estimation of the number of nucleotide substitutions in the control region of mitochondrial DNA in humans and chimpanzees. Mol Biol Evol. 1993;10:512–26.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Tamura K, Stecher G, Kumar S. MEGA11: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 11. Mol Biol Evol. 2021;38:3022–7. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar