Volume 9, Number 6—June 2003

Dispatch

Anthroponotic Cutaneous Leishmaniasis, Kabul, Afghanistan

Figure

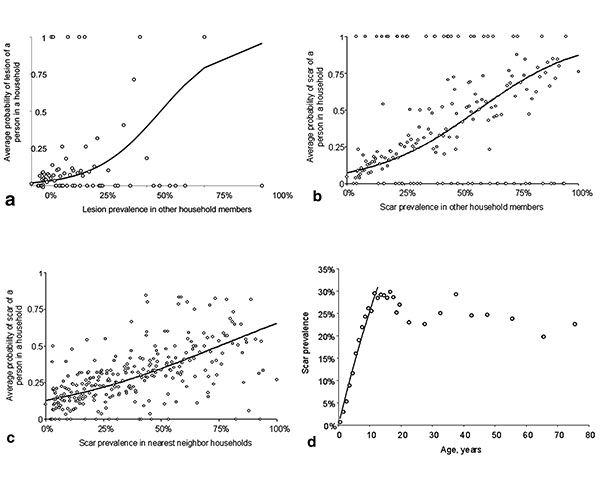

Figure. A, the average probability of having a lesion at different levels of lesion prevalence recorded among other members of the same household (open circles) and the unadjusted fit (solid line) from the logistic regression. B, the average probability of having a scar at different levels of scar prevalence recorded in other members of the same household (open circles) and the unadjusted fit (solid line) from the logistic regression. C, average probability of having a scar at different levels of scar prevalence in nearest neighbor households (open circles) and the unadjusted fit (solid line) from the logistic regression. D, force of infection, λ, can be estimated from the age-prevalence data, where the proportion, P, of persons with ACL at age a (where a is age at last birthday plus 0.5 years) is given by P(a) = 1-exp(-λa) (6). If one assumes that age-independent transmission started 12 years earlier (1), λ was estimated by maximum likelihood by using the observed age-prevalence data for children <12 y of age.

References

- Ashford R, Kohestany K, Karimzad M. Cutaneous leishmaniasis in Kabul: observations on a prolonged epidemic. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1992;86:361–71.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Killick-Kendrick R, Killick-Kendrick M, Tang Y. Anthroponotic cutaneous leishmaniasis in Kabul: the high susceptibility of Phlebotomus sergenti to Leishmania tropica. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1995;89:477. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Griffiths WDA. Old World cutaneous leishmaniasis. In: Peters W, Killick-Kendrick R, editors. The leishmaniases in biology and medicine. London: Academic Press; 1987. p. 617–43.

- World Health Organization. Cutaneous leishmaniasis, Afghanistan. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 2002;29:246.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Rowland M, Munir A, Durrani N, Noyes H, Reyburn H. An outbreak of cutaneous leishmaniasis in an Afghan refugee settlement in north-west Pakistan. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1999;93:133–6. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Williams B, Dye CM. Maximum-likelihood for parasitologists. Parasitol Today. 1994;10:489–93. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Trouiller P, Torreele E, Olliaro P, White N, Foster S, Wirth D, Drugs for neglected diseases: a failure of the market and a public health failure? Trop Med Int Health. 2001;6:945–51. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Boelaert M, Le Ray D, Van Der Stuyft P. How better drugs could change kala-azar control. Lessons from a cost-effectiveness analysis. Trop Med Int Health. 2002;7:955–9. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar