Volume 6, Number 1—February 2000

Perspective

From Shakespeare to Defoe: Malaria in England in the Little Ice Age

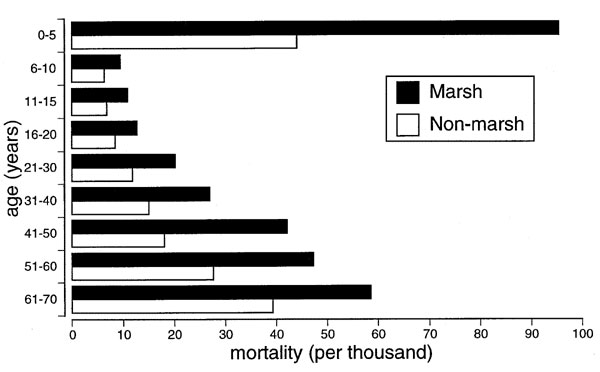

Figure 4

Figure 4. Age-specific death rates (per 1,000) in Essex parishes, c. 1800. Drawn from Dobson (15).

References

- Lamb HH. Climate, history and the modern world. London: Routledge; 1995.

- Rasool SI, Schneider SH. Atmospheric carbon dioxide and aerosols: effects of large increases on global climate. Science. 1971;175:138–41. DOIGoogle Scholar

- Calder N. The weather machine. New York: Viking; 1974.

- Houghton JT, Meira Filho LG, Callander BA, Harris N, Kattenberg A, Maskell K, eds. The science of climate change: contribution of Working Group I to the second assessment of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge: University Press; 1995.

- Lindzen RS. Can increasing carbon dioxide cause climate change? Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:8335–42. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Soon W, Baliunas SL, Robinson AB, Zachary WR. Environmental effects of increased atmospheric carbon dioxide. Clim Res. 1999;13:149–64. DOIGoogle Scholar

- Watson RT, Zinyowera MC, Moss RH, eds. Impacts, adaptations and mitigation of climate change: scientific-technical analyses. Contribution of Working Group II to the Second Assessment of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge: University Press; 1995.

- Patz JA, Epstein PR, Burke TA, Balbus JM. Global climate change and emerging infectious diseases. JAMA. 1996;275:217–23. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Martens WJM, Slooff R, Jackson EK. Climate change, human health, and sustainable development. Bull World Health Organ. 1997;75:583–8.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Epstein PR, Diaz HF, Elias S, Grabherr G, Graham NE, Martens WJM, Biological and physical signs of climate change: focus on mosquito-borne diseases. Bull Am Meteorol Soc. 1998;79:409–17. DOIGoogle Scholar

- Houghton JT, Meira Filho LG, Callander BA, Harris N, Kattenberg A, Maskell K, eds. The regional impacts of climate change. Cambridge: University Press; 1998.

- Martens WJM. Health impacts of climate change and ozone depletion: an ecoepidemiologic modeling approach. Environ Health Perspect. 1998;106(Suppl):241–51. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Bruce-Chwatt LJ, de Zulueta J. The rise and fall of malaria in Europe, a historico-epidemiological study. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1980.

- Grove JM. Little ice age. London: Routledge Keegan and Paul; 1988.

- Dobson MJ. "Marsh Fever" the geography of malaria in England. J Hist Geogr. 1980;6:357–89. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Dobson MJ. Contours of death and disease in early modern England. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1997.

- Dobson MJ. Malaria in England: a geographical and historical perspective. Parassitologia. 1994;36:35–60.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Macdonald A. On the relation of temperature to malaria in England. J R Army Med Corps. 1920;35:99–119.

- Bruce-Chwatt LJ. Bruce-Chwatt's essential malariology. Gilles HM, Warrell DA, editors. London: Edward Arnold; 1993.

- Dock G. Robert Talbor, Madame de Sévigné, and the introduction of cinchona: an episode illustrating the influence of women in medicine. Ann Med Hist. 1927;4:241–7.

- Siegel RE, Poynter FNL. Robert Talbor, Charles II and cinchona: a contemporary document. Med Hist. 1962;6:82–5.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Dobson MJ. Bitter-sweet solutions for malaria: exploring natural remedies from the past. Parassitologia. 1998;40:69–81.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Defoe D. A tour through the whole island of Great Britain. London: Penguin; 1986.

- Russell PF. World-wide malaria distribution, prevalence, and control. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1956;5:937–65.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Ekblom T. Les races Suédoises de l'Anopheles maculipennis et leur role épidémiologique. Bull Soc Pathol Exot. 1938;31:647–55.

- Renkonen KO. Über das Vorkommen von Malaria in Finnland. Acta Med Scand. 1944;119:261–75.

- Faust EC. The distribution of malaria in North America, Mexico, Central America and the West Indies. In: A symposium on human malaria, with special reference to North America and the Caribbean Region. Washington: American Association for the Advancement of Science; 1941. p. 8-18.

- Fisk GH. Malaria and the Anopheles mosquito in Canada. Can Med Assoc J. 1931; (

Dec ):679–83.PubMedGoogle Scholar - Macculloch J. Malaria: an essay on the production and propagation of this poison and on the nature and localities of the places by which it is produced: with an enumeration of the diseases caused by it, and to the means of preventing or diminishing them, both at home and in the naval and military service. London: Longman & Co; 1827.

- Russell PF. Man's mastery of malaria. London: Oxford University Press; 1955.

- Loevinsohn ME. Climatic warming and increased malaria incidence in Rwanda. Lancet. 1994;343:714–8. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- McMichael AJ, Patz J, Kovats RS. Impacts of global environmental change on future health and health care in tropical countries. Br Med Bull. 1998;54:475–88.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Hackett LW. The malaria of the Andean region of South America. Rev Inst Salubr Enferm Trop. 1945;6:239–52.

- Reiter P. Global warming and vector-borne disease in temperate regions and at high altitude. Lancet. 1998;351:839–40. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Mouchet J, Manguin S, Sircoulon J, Laventure S, Faye O, Onapa AW, Evolution of malaria in Africa for the past 40 years: impact of climatic and human factors. J Am Mosq Control Assoc. 1998;14:121–30.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Rodhain F, Charmot G. Evaluation des risques de reprise de transmission du paludisme en France. Med Mal Infect. 1982;12:231–6. DOIGoogle Scholar

- Sabatinelli G. Malaria situation and implementation of the global malaria control strategy in the WHO European region. WHO Expert Committee on Malaria 1998;MAL/EC20/98.9.

- Molineaux L, Gramiccia G. The Garki project. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1980.

1St. Thomas' Hospital (1213), in the Borough of Lambeth, was on the edge of the River Thames, surrounded by tidal marshes. Parliament met in two buildings at a similar site in the Borough of Westminster, directly across the river. Both areas were notoriously malarious. Centuries later, the American Founding Fathers followed British parliamentary procedure in choosing a site for their new nation's capital at the edge of a malarious swamp, later referred to as "A Mud-hole Equal to the Great Serbonian Bog." The Serbonian Bog probably refers to the vast flood plains of the Danube that border northern Serbia and Bulgaria. The Balkan region was the last major stronghold of malaria in Europe. Malaria was finally eliminated there in 1975.