Volume 8, Number 4—April 2002

Historical Review

Megadrought and Megadeath in 16th Century Mexico

Figure 1

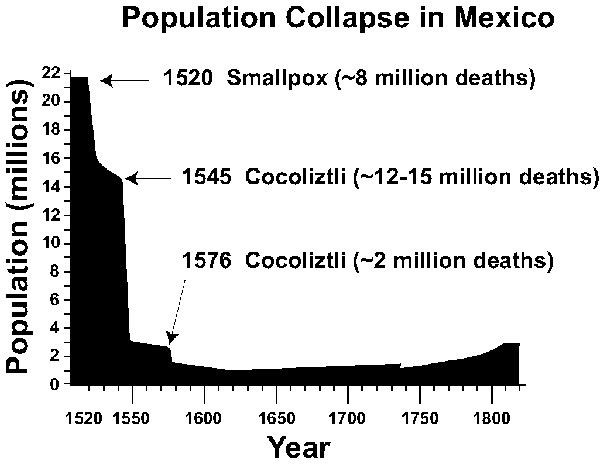

Figure 1. The 16th-century population collapse in Mexico, based on estimates of Cook and Simpson (1). The 1545 and 1576 cocoliztli epidemics appear to have been hemorrhagic fevers caused by an indigenous viral agent and aggravated by unusual climatic conditions. The Mexican population did not recover to pre-Hispanic levels until the 20th century.

References

- Cook SF, Simpson LB. The Population of Central Mexico in the Sixteenth Century. Ibero Americana Vol. 31, Berkeley: University of California Press; 1948.

- Gerhard P. A guide to the historical geography of New Spain. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press; 1993.

- Hugh T. Conquest, Montezuma, Cortez, and the Fall of Old Mexico. New York: Simon and Schuster; 1993.

- Acuna-Soto R, Caderon Romero L, Maguire JH. Large epidemics of hemorrhagic fevers in Mexico 1545-1815. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2002. In press.

- Marr JS, Kiracofe JB. Was the Huey Cocoliztli a haemorrhagic fever? Med Hist. 2000;44:341–62.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Stahle DW, Cleaveland MK, Therrell MD, Villanueva-Diaz J. Tree-ring reconstruction of winter and summer precipitation in Durango, Mexico, for the past 600 years. 10th Symposium Global Change Studies. Boston: American Meteorological Society, 1999; 317-8.

- Stahle DW, Cook ER, Cleaveland MK, Therrell MD, Meko DM, Grissino-Mayer HD, Tree-ring data document 16th century megadrought over North America. Eos. 2000;81:121–5. DOIGoogle Scholar

- Schmaljohn C, Hjelle B. Hantaviruses: a global disease problem. Emerg Infect Dis. 1997;3:95–104.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Hjelle B, Glass GE. Outbreak of hantavirus infection in the Four Corners region of the United States in the wake of the 1997-1998 El Nino-Southern Oscillation. J Infect Dis. 2000;181:1569–73. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Malvido E. Cronologia de las epidemias y crisis agricolas de la epoca colonial. Hist Mex. 1973;89:96–101.

- Peters CJ. Hemorrhagic fevers: How they wax and wane. In: Scheld WM, Armstong D, Hughes JM, editors. Emerging infections. Washington DC: American Society for Microbiology, 1998;15-25.

Page created: July 15, 2010

Page updated: July 15, 2010

Page reviewed: July 15, 2010

The conclusions, findings, and opinions expressed by authors contributing to this journal do not necessarily reflect the official position of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, the Public Health Service, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, or the authors' affiliated institutions. Use of trade names is for identification only and does not imply endorsement by any of the groups named above.