Volume 9, Number 12—December 2003

Research

Global Distribution of Rubella Virus Genotypes

Figure 1

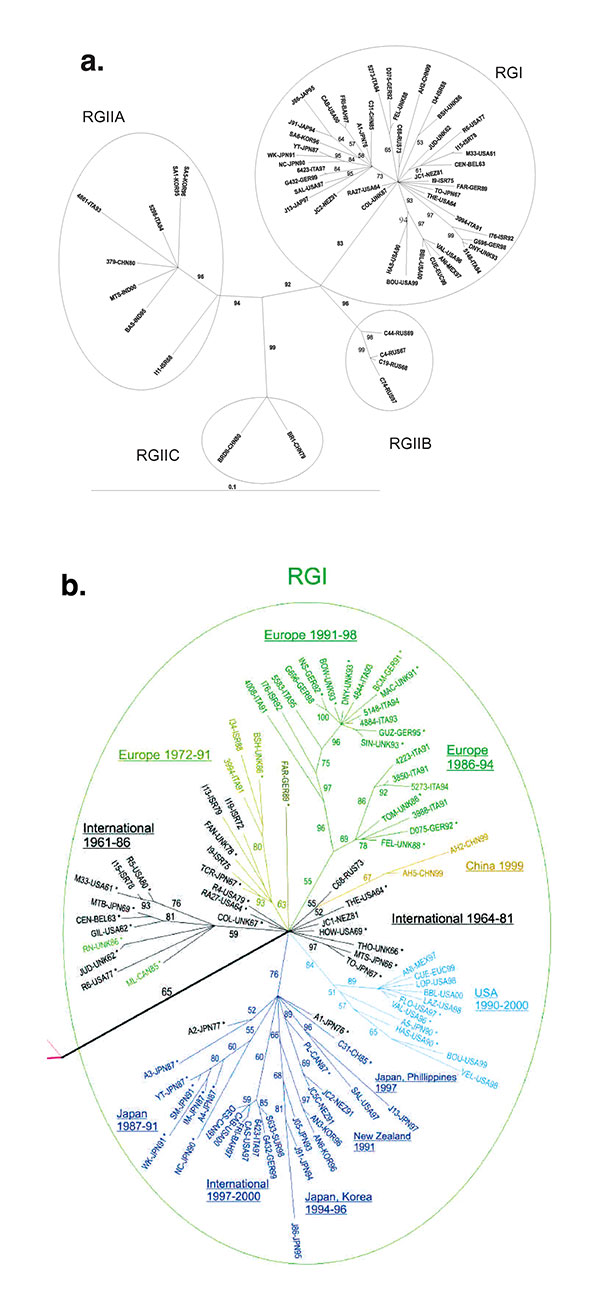

Figure 1. Phylogenetic trees. Unrooted tree was made by the maximum likelihood method in the Tree-Puzzle 5.0 program (25,000 puzzling steps for the tree in A; 10,000 puzzling steps for the tree in B) using the complete E1 gene sequence (1179 nt). Bootstrapping values (out of 100) for each node are given. The tree in A was constructed with half of the rubella genotype I (RGI) and all of the RGII sequences (to allow the reader to read the RGI virus designations); the tree in B is a blowup of the RGI node from a tree constructed with all of the sequences. In B, sequences used in the previous study (8) are designated by an (*), and sequences of viruses isolated before 1980 are in black. Branches are color-coded as follows: RGI Intercontinental (International) 1961–1986 and 1964–1981, black; RGI Europe 1972–1991, gold; RGI Europe 1986–1994 and Europe 1991–1998, green; RGI China, 1999, gold; RGI USA, 1990–2000, light blue; and branch containing sub-branches from Japan 1987–1991, Intercontinental (International) 1997–2000, Japan, Korea 1994–1996, New Zealand, 1991, and Japan-Philippines, 1997, dark blue. Of these, the black Intercontinental (International), green Europe, light-blue USA, and dark-blue branches were recognized in the previous study (the light-blue branch as US-Japan and the dark-blue branch as Japan-Hong Kong).

References

- Chantler J, Wolinsky JS, Tingle A. Rubella virus. In: Knipe DM, Howley PM, editors. Fields virology. 4th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams, and Wilkins; 2001. p. 963–90.

- Plotkin SA. Rubella. In: Plotkin SA, Orenstein WA, editors. Vaccines. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Saunders;1999. p. 409–40.

- World Health Organization. Preventing congenital rubella syndrome. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 2000;75:289–96.

- Castillo-Solorzano C, Carrasco P, Tambini G, Reef S, Brana M, De Quadros CA. New horizons in the control of rubella and prevention of congenital rubella syndrome in the Americas. J Infect Dis. 2003;187(Suppl 1):S146–52. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Venczel L, Rota J, Dietz V, Morris-Glasgow V, Siqueira M, Quirogz E, The measles laboratory network in the region of the Americas. J Infect Dis. 2003;187(Suppl 1):S140–5. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Frey TK, Abernathy ES. Identification of strain-specific nucleotide sequences in the RA27/3 rubella virus vaccine. J Infect Dis. 1993;168:854–64.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Frey TK, Abernathy ES, Bosma TJ, Starkey WG, Corbett KM, Best JM, Molecular analysis of rubella virus epidemiology across three continents, North America, Europe, and Asia, 1961–1977. J Infect Dis. 1998;178:642–50. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Zheng DP, Zhu H, Revello MG, Gerna G, Frey TK. Phylogenetic analysis of rubella virus isolated during a period of epidemic transmission in Italy, 1991–1997. J Infect Dis. 2003;187:1587–97. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Reef SE, Frey TK, Theall K, Abernathy E, Burnett CL, Icenogle J, The changing epidemiology of rubella in the 1990s, on the verge of elimination and new challenges for control and prevention. JAMA. 2002;287:464–72. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Katow S, Minahara H, Fukushima M, Yamaguchi Y. Molecular epidemiology of rubella by nucleotide sequences of the rubella virus E1 gene in three East Asia countries. J Infect Dis. 1997;176:602–16. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Bosma TJ, Best JM, Corbett KM, Banatvala JE, Starkey WG. Nucleotide sequence analysis of a major antigenic domain of the E1 glycoprotein of 22 rubella virus isolates. J Gen Virol. 1996;77:2523–30. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Pugachev KV, Abernathy ES, Frey TK. Genomic sequence of the RA27/3 vaccine strain of rubella virus. Arch Virol. 1997;142:1165–80. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Schmidt HA, Strimmer K, Vingron M, von Haeseler A. TREE-PUZZLE: maximum likelihood phylogenetic analysis using quartets and parallel computing. Bioinformatics. 2002;18:502–4. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Hasegawa M, Kishino H, Yano K. Dating of the human-ape splitting by a molecular clock of mitochondrial DNA. J Mol Evol. 1985;22:160–74. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Page RDM. TreeView: an application to display phylogenetic trees on personal computers. Comput Appl Biosci. 1996;12:357–8.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Zheng DP, Zhang LB, Fang ZY, Yang CF, Mulders M, Pallansch MA, Distribution of wild type 1 poliovirus genotypes in China. J Infect Dis. 1993;168:1361–7.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Jin L, Vyse A, Brown DW. The role of RT-PCR assay of oral fluid for diagnosis and surveillance of measles, mumps and rubella. Bull World Health Organ. 2002;80:76–7.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Vyse AJ, Lin L. An RT-PCR assay using oral fluid samples to detect rubella virus genome for epidemiological surveillance. Mol Cell Probes. 2002;16:93–7. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Bosma TJ, Corbett KM, Eckstein MB, O’Shea S, Vijayalakshmi P, Banatvala JE, Use of PCR for prenatal and postnatal diagnosis of congenital rubella. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:2881–7.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Bosma TJ, Corbett KM, O’Shea S, Banatvala JE, Best JM. PCR for detection of rubella virus RNA in clinical samples. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:1075–9.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Tanemura M, Suzumori K, Yagami Y, Katow S. Diagnosis of fetal rubella infection with reverse transcription and nested polymerase chain reaction: a study of 34 cases diagnosed in fetuses. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;174:578–82. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Adams SD, Tzeng W-P, Chen M-H, Frey TK. Analysis of intermolecular RNA-RNA recombination by rubella virus. Virology. 2003;309:258–71. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Ando T, Noel JS, Fankhauser L. Genetic classification of “Norwalk-like viruses.”. J Infect Dis. 2000;181(Suppl 2):336–48. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

1Current address: Respiratory and Enteric Viruses Branch, Division of Viral and Rickettsial Diseases, National Center for Infectious Diseases, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA, USA.