Volume 10, Number 7—July 2004

Research

Detection of SARS-associated Coronavirus in Throat Wash and Saliva in Early Diagnosis

Figure 1

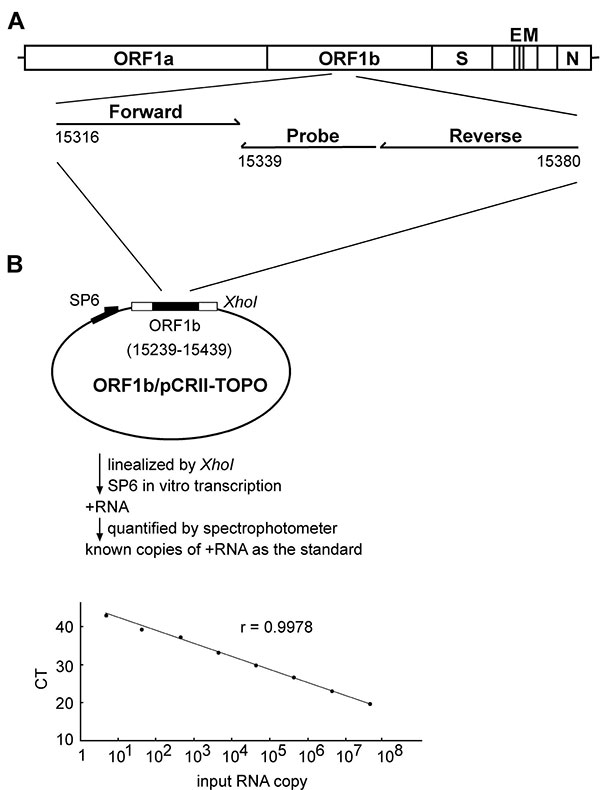

Figure 1. Quantification of the severe acute respiratory syndrome-associated coronavirus (SARS-CoV) RNA by real-time reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) assay. (A) Location of the forward and reverse primers and probe in the genome of SARS-CoV, with the genome positions shown according to the Urbani strain (20). (B) A schematic diagram of the construct, ORF1b/pCRII-TOPO, and the protocol for generating the in vitro transcribed RNA as the standard for the real-time RT-PCR assay is shown. The relationship between known input RNA copies to the threshold cycle (CT) is shown at the bottom.

References

- Tsang KW, Ho PL, Ooi GC, Yee WK, Wang T, Chan-Yeung M, A cluster of cases of severe acute respiratory syndrome in Hong Kong. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1977–85. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Lee N, Hui D, Wu A, Chan P, Cameron P, Joynt GM, A major outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome in Hong Kong. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1986–94. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Poutanen SM, Low DE, Henry B, Finkelstein S, Rose D, Green K, Identification of severe acute respiratory syndrome in Canada. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1995–2005. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Update: outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome—worldwide. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2003;52:241–8.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- World Health Organization. Summary of probable SARS cases with onset of illness from 1 November 2002 to 31 July 2003. [2003 May 14]. Available from: http://www.who.int/csr/sars/country/2003_04_21/en/

- Ksiazek TG, Erdman D, Goldsmith C, Zaki SR, Peret T, Emery S, A novel coronavirus associated with severe acute respiratory syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1953–66. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Drosten C, Gunther S, Preiser W, Werf S, Brodt HR, Becker S, Identification of a novel coronavirus in patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1967–76. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Peiris JSM, Lai ST, Poon LLM, Guan Y, Yam LYC, Lim W, Coronavirus as a possible cause of severe acute respiratory syndrome. Lancet. 2003;361:1319–25. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Kuiken T, Fouchier RAM, Schutten M, Rimmelzwann GF, Amerongen G, Riel D, Newly discovered coronavirus as the primary cause of severe acute respiratory syndrome. Lancet. 2003;362:263–70. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Riley S, Fraser C, Donnelly CA, Ghani AC, Abu-Raddad LJ, Hedley AJ, Transmission dynamics of the etiological agent of SARS in Hong Kong: impact of public health interventions. Science. 2003;300:1961–6. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Lipsitch M, Cohen T, Cooper B, Robins JM, Ma S, James L, Transmission dynamics and control of the severe acute respiratory syndrome. Science. 2003;300:1966–70. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- World Health Organization. Consensus document on the epidemiology of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS). [cited 2004 Feb 18]. Available from: http://www.who.int /csr/sars/en/index.html

- Donnelly CA, Ghani AC, Leung GM, Hedley AJ, Fraser C, Riley S, Epidemiological determinants of spread of causal agent of severe acute respiratory syndrome in Hong Kong. Lancet. 2003;361:1761–6. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Peiris JSM, Chu CH, Cheng VCC, Chan KS, Hung IFN, Poon LLM, Clinical progression and viral load in a community outbreak of coronavirus-associated SARS pneumonia: a prospective study. Lancet. 2003;361:1773–8. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- World Health Organization. Case definitions for surveillance of SARS. [cited 2003 May 1]. Available from: http://www.who.int/csr/sars/casedefinition/en/

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Severe acute respiratory syndrome—Taiwan 2003. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2003;52:461–6.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Interim domestic infection control precautions for aerosol-generating procedures on patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS). [cited 2003 Oct 4]. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/sars/aerosolin fectioncontrol.htm.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Interim laboratory biosafety guidelines for handling and processing specimens associated with severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS). [2003 Oct 4]. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/sars/sarslabguide.htm

- Hsueh PR, Hsiao SH, Yeh SH, Wang WK, Chen PJ, Wang JT, Microbiologic characterization, serologic responses, and clinical manifestations in severe acute respiratory syndrome, Taiwan. Emerg Infect Dis. 2003;9:1163–7.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Rota PA, Oberste MS, Monroe S, Allan NW, Campagnoli R, Icenogle JP, Characterization of a novel coronavirus associated with severe acute respiratory syndrome. Science. 2003;300:1394–9. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Marra MA, Jones SJM, Astell CR, Holt RA, Brook-Wilson A, Butterfield YSN, The genome sequence of the SARS-associated coronavirus. Science. 2003;300:1399–404. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Wang WK, Sung TL, Tsai YC, Kao CL, Chang SM, King CC. Detection of dengue virus replication in peripheral blood mononuclear cells from dengue virus type 2-infected patients by a reverse transcription-real-time PCR assay. J Clin Microbiol. 2002;40:4472–8. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Kwok S, Higuchi R. Avoiding false positive with PCR. Nature. 1989;339:237–8. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Nicholls JM, Poon LLM, Lee KC, Ng WF, Lai ST, Leung CY, Lung pathology of fatal severe acute respiratory syndrome. Lancet. 2003;361:1773–8. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Lai MMC, Holmes KV. Coronaviridae: the virus and their replication. In: Knipe DM, Howley PM, Griffin DE, Lamb RA, Martin MA, Roizman B, et al., editors. Fields virology, 4th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott William and Wilkins; 2001. p. 1163–85.

- Seto WH, Tsang D, Yung RWH, Ching TY, Ng TK, Ho M, Effectiveness of precautions against droplets and contact in prevention of nosocomial transmission of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS). Lancet. 2003;361:1519–20. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Cluster of severe acute respiratory syndrome cases among protected health-care workers—Toronto, Canada, April 2003. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2003;52:433–6.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- World Health Organization. Sampling for severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) diagnostic tests. [2003 Oct 4]. Available from: http://www.who.int/csr/sars/sampling/en/

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Guidelines for collection of specimens from potential cases of SARS. [cited 2003 Dec 26]. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov /ncidod/sars/ specimen_collection_sars2.htm

- Tsang OTY, Chau TN, Choi KW, Tso EYK, Lim W, Chiu MC, Coronavirus-positive nasopharyngeal aspirate as predictor for severe acute respiratory syndrome mortality. Emerg Infect Dis. 2003;9:1381–7.PubMedGoogle Scholar

Page created: January 27, 2011

Page updated: January 27, 2011

Page reviewed: January 27, 2011

The conclusions, findings, and opinions expressed by authors contributing to this journal do not necessarily reflect the official position of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, the Public Health Service, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, or the authors' affiliated institutions. Use of trade names is for identification only and does not imply endorsement by any of the groups named above.