Volume 14, Number 8—August 2008

Research

Diverse Contexts of Zoonotic Transmission of Simian Foamy Viruses in Asia

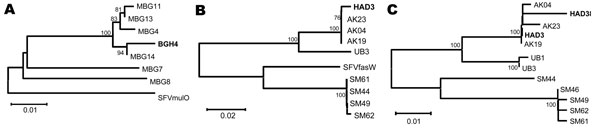

Figure 2

Figure 2. Phylogenetic trees of simian foamy virus (SFV) sequences derived from 3 persons. Human-derived SFV sequences (shown in boldface) were compared with those obtained from macaques of the group with which the person had been in contact and to SFV from other macaques of the same species but different geographic origin. Neighbor-joining trees A and B used gag PCR primers (1,124 bp), and C used pol PCR primers (445 bp). A) SFV gag–derived from BGH4 DNA clusters more closely (94% of bootstrap samplings) with gag sequences from 4 Macaca mulatta that ranged throughout her village (MBG4, MBG11, MBG13, and MBG14) than with gag sequences obtained from Bangladeshi performing monkeys, M. mulatta (MBG7, MBG8), of unknown origin. BGH4 gag is equidistant from gag of MBG7, MBG8, and virus obtained from SFVmulO, an M. mulatta of unknown origin housed at the Oregon National Regional Primate Center. B) SFV gag from HAD3, a worker at a Bali monkey temple, grouped with gag from several M. fascicularis (AK4, AK19, AK23) found at the same temple (100% of bootstrap samplings). UB3 is also an M. fascicularis Bali temple monkey that inhabited a temple ≈15 km away. HAD3-derived gag is less similar to M. fascicularis from Singapore (SM) and SFVfasW, an M. fascicularis housed at the Washington National Primate Research Center. C) Analysis of pol confirms the relationships (100% of bootstrap samplings) between SFV sequences isolated from humans (HAD3 and HAD38) and those in the corresponding nonhuman primate populations with which they reported contact (AK4, AK19, AK23). HAD3 and HAD38 worked at the same temple site where AK are found. UB1 and UB3 are M. fascicularis from a nearby monkey temple. Scale bars indicate number of nucleotide substitutions per site.