Volume 16, Number 2—February 2010

Dispatch

White-Nose Syndrome Fungus (Geomyces destructans) in Bat, France

Figure 2

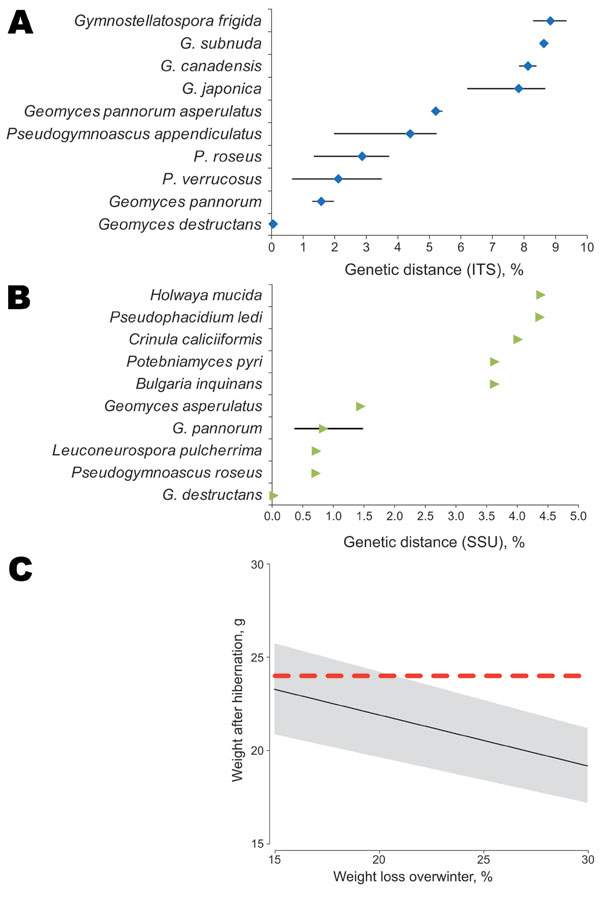

Figure 2. Genetic distance between fungus A) internal transcribed spacer (ITS) (474 nt) and B) small subunit (SSU) rRNA (1,865 nt) gene sequences and other closely related fungus species present in GenBank. Results are based on pairwise sequence comparisons with gaps and missing data removed. Error bars in panels A and B indicate mean ± SD. C) Estimation of weight of Myotis myotis bats after hibernation as a function of the range of percentage of weight loss reported. Posthibernation of a bat’s weight was estimated from prehibernation measured weights (n = 155 bats) minus winter fat loss. A strong positive relationship exists between body mass and fat mass during prehibernation (8). Fat reserves between 15% and 30% of body mass at the onset of hibernation have been reported to be necessary for Myotis species to survive winter (9). The posthibernation weight (Wpost) was thus estimated as Wpost = Wpre – (Wpre × Wloss/100), where Wpre is prehibernation weight and Wloss is percentage of body mass lost during hibernation. Mean ± SD prehibernation weight of 155 bats captured in France during August–October 2009 (27.42 ± 2.87 g) was used for the estimate. Black line represents the mean, gray area represents the mean ± SD, and red dashed line represents the 24-g weight of the bat caught in France with white-nose syndrome posthibernation. The bat was in good condition (24 g) because it weighed more than the expected average for a posthibernating bat despite having Geomyces destructans growth on its snout.

References

- Turner GG, Reeder DM. Update of white nose syndrome in bats, September 2009. Bat Research News. 2009;50:47–53.

- Simmons NB. Order Chiroptera. In: Wilson DE, Reeder DM, editors. Mammal species of the world: a taxonomic and geographic reference, 3rd ed. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press; 2005. p. 312–529.

- Consensus statement. Austin (TX): Second WNS Emergency Science Strategy Meeting; 2009 May 27–28 [cited 2009 Nov 30]. http://www.batcon.org/pdfs/whitenose/ConsensusStatement2009.pdf

- Meteyer CU, Buckles EL, Blehert DS, Hicks AC, Green DE, Shearn-Bochsler V, Histopathologic criteria to confirm white-nose syndrome in bats. J Vet Diagn Invest. 2009;21:411–4.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Blehert DS, Hicks AC, Behr M, Meteyer CU, Berlowski-Zier BM, Buckles EL, Bat white-nose syndrome: an emerging fungal pathogen? Science. 2009;323:227. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Gargas A, Trest MT, Christiensen M, Volk TJ, Blehert DS. Geomyces destructans sp. nov. associated with bat white-nose syndrome. Mycotaxon. 2009;108:147–54.

- Gianni C, Caretta G, Romano C. Skin infection due to Geomyces pannorum var. pannorum. Mycoses. 2003;46:430–2. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Kunz TH, Weazen JA, Burnett CD. Changes in body mass and fat reserves in pre-hibernating little brown bats (Myotis lucifugus). Ecoscience. 1998;5:8–17.

- Johnson SA, Brack VJ, Rolley RE. Overwinter weight loss of Indiana bats (Myotis sodalis) from hibernacula subject to human visitation. Am Midl Nat. 1998;139:255–61. DOIGoogle Scholar

- Dietz C, Von Helversen O, Dietmar N. Bats of Britain, Europe and northwest Africa. London: A and C Black Publishers Ltd.; 2009.

- Voyles J, Young S, Berger L, Campbell C, Voyles WF, Dinudom A, Pathogenesis of chytridiomycosis, a cause of catastrophic amphibian declines. Science. 2009;326:582–5. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Fisher MC, Garner TW, Walker SF. Global emergence of Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis and amphibian chytridiomycosis in space, time, and host. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2009;63:291–310. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Williams-Guillen K, Perfecto I, Vandermeer J. Bats limit insects in a neotropical agroforestry system. Science. 2008;320:70. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Federico P, Hallam TG, McCracken GF, Purucker ST, Grant WE, Correa-Sandoval AN, Brazilian free-tailed bats as insect pest regulators in transgenic and conventional cotton crops. Ecol Appl. 2008;18:826–37. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Kalka MB, Smith AR, Kalko EK. Bats limit arthropods and herbivory in a tropical forest. Science. 2008;320:71. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar