Volume 17, Number 10—October 2011

Letter

Swinepox Virus Outbreak, Brazil, 2011

To the Editor: Swinepox virus (SWPV), which replicates only in swine, belongs to the Suipoxvirus genus of the Poxviridae family. It is the etiologic agent of a skin disease of pigs, characterized by generalized pustular lesions and associated with high rates of illness (occasionally >80%). It occurs mainly on farms with poor management and housing conditions and affects primarily pigs <3 months of age; adult pigs show milder signs. The disease is mechanically transmitted by pig lice or through direct animal contact (1). Vaccinia virus (VACV; Orthopoxvirus genus) also causes a similar pustular disease in pigs that is difficult to distinguish clinically from SWPV infections. VACV infections were common during smallpox vaccination campaigns, when VACV was transmitted to domestic animals from lesions of vaccinees (1,2).

Swinepox disease has a worldwide distribution, and 4 outbreaks of similar infections were reported in pig herds in Brazil during 1976–2001 (3). Nevertheless, the etiologic agents of these outbreaks have never been identified through molecular techniques. Specific virus identification in such infections is particularly relevant in Brazil, considering the persistence of VACV in nature in this country, causing frequent outbreaks of pustular skin disease in dairy cattle (4–6). Therefore, distinguishing between SWPV and VACV infections during outbreaks of pustular disease in pigs is essential for evaluating whether VACV infection might have spread to pigs and whether SWPV could be detected in Brazil.

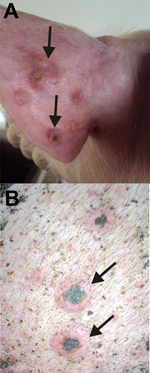

We describe the molecular identification of SWPV as the etiologic agent of an outbreak of pustular disorder in pig herds. In November 2010 and January 2011, ≈850 of 3,460 animals on 3 pig farms in Holambra, São Paulo, Brazil, had generalized pustular lesions on the body, fever (38.0°C–39.7°C) and mild weight loss. Lesions evolved from macules or papules to umbilicated lesions with pustular content, followed by crusting (Figure A1). Secondary dermatitis was also noticed. Healing occurred after 3–4 weeks, but the disease started subsequently in previously healthy animals. Although the first clinical signs of disease started in the nursery units (pigs 40–50 days old), nearly 70% of the sick pigs were at the finishing units (pigs 127–134 days old), where elevated animal density and deficient sanitation conditions were observed. These findings may account for the high attack rate (nearly 50%) in finisher pigs, although overall illness was moderate (nearly 25%) when animals from all units were analyzed together. No deaths were associated with the outbreak, in concordance with the low death rates reported for SWPV infections (<5%) (1). The affected farms belonged to the same owner, who reported frequent movement of animals between the farms.

Scabs from 7 animals were used for DNA extraction (4), followed by PCR detection of poxvirus DNA (7). We used primers designed to anneal to gene regions conserved in different poxviruses: FP-A2L, 5′-TAGTTTCAGAACAAGGATATG-3′ and RP-A2L, 5′-TTCCCATATTAATTGATTACT-3′ directed the amplification of a 482-bp fragment of the virus late transcription factor–3 (www.poxvirus.org); primer sets for the DNA polymerase gene (543-bp fragment) and DNA topoisomerase gene (344-bp fragment) were previously described (7). Amplicons were directly sequenced as described (4,5). Consensus primers that specifically detect the full-length hemagglutinin gene of Eurasian-African orthopoxviruses were used to investigate VACV in the samples (4).

[[AA:FA:PREVIEWHTML]]

The nucleotide sequences obtained for the fragments of the DNA polymerase, DNA topoisomerase, and virus late transcription factor–3 of the clinical specimens were aligned with sequences from other poxviruses available in the public database (GenBank). They showed 100% nt identity with their orthologs of SWPV Nebraska strain. Concatenated amino acid alignments were used for phylogenetic inference (Figure). The clinical isolates and SWPV branched together in the phylogenetic tree with high bootstrap support. No amplification of the hemagglutinin gene was obtained, demonstrating that the animals were not infected with VACV. Samples were also negative for Erysipelothrix spp. (by PCR and ELISA) and porcine circovirus-2 (by PCR).

Outbreaks of swinepox disorders have been frequently reported in Europe, North America, and Oceania, and special attention has been given to congenital cases, which usually lead to high case-fatality rates (2,8,9). Our data identified SWPV as the cause of a recent outbreak in Brazil and suggest that previous outbreaks in the neighboring municipality of Campinas in 1976 and 1980 (3) may have been caused by SWPV as well because pigs are the only host and reservoir of the virus. Further sequencing analysis of the virus isolates will be necessary to characterize the strain of SWPV circulating in Brazil.

Recently, an outbreak of VACV-related disease in horses was reported in southern Brazil, which alerted the scientific community to the possible spread of this disorder to animal hosts other than dairy cattle (10). However, our data clearly demonstrate that this outbreak in pigs does not represent a spread of VACV infection, despite frequent reports of VACV-related outbreaks in dairy cows in São Paulo State (6). Therefore, the differential diagnosis of skin diseases of pigs might be a useful tool in epidemiologic surveys to access VACV spread and host range in Brazil.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by grants from the Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico, Ministério da Agricultura, Pecuária e Abastecimento, Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado do Rio de Janeiro, and Instituto Nacional de Pesquisa Translacional na Amazônia to C.R.D.; M.L.G.M. received a fellowship from the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior.

References

- House JA, House CA. Swine pox. In: Leman AD, Straw BE, Mengeling WL, D’Allaire S, Taylor DJ, editors. Diseases of swine. 7th ed. Ames (IA): Iowa State University Press; 1994. p. 358–61.

- Cheville NF. Immunofluorescent and morphologic studies on swinepox. Pathol Vet. 1966;3:556–64. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Bersano JG, Catroxo MH, Villalobos EM, Leme MC, Martins AM, Peixoto ZM, Varíola suína: estudo sobre a ocorrência de surtos nos estados de São Paulo e Tocantins, Brasil. Arq Inst Biol (São Paulo). 2003;70:269–78 [ cited 2011 Aug 3]. http://www.biologico.sp.gov.br/docs/arq/V70_3/bersano.pdf

- Medaglia ML, Pessoa LC, Sales ER, Freitas TR, Damaso CR. Spread of Cantagalo virus to northern Brazil. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009;15:1142–3. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Damaso CR, Esposito JJ, Condit RC, Moussatche N. An emergent poxvirus from humans and cattle in Rio de Janeiro state: Cantagalo virus may derive from Brazilian smallpox vaccine. Virology. 2000;277:439–49. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Megid J, Appolinario CM, Langoni H, Pituco EM, Okuda LH. Vaccinia virus in humans and cattle in southwest region of São Paulo state, Brazil. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2008;79:647–51.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Bracht AJ, Brudek RL, Ewing RY, Manire CA, Burek KA, Rosa C, Genetic identification of novel poxviruses of cetaceans and pinnipeds. Arch Virol. 2006;151:423–38. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Jubb TF, Ellis TM, Peet RL, Parkinson J. Swinepox in pigs in northern Western Australia. Aust Vet J. 1992;69:99. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Borst GH, Kimman TG, Gielkens AL, van der Kamp JS. Four sporadic cases of congenital swinepox. Vet Rec. 1990;127:61–3.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Brum MC, Anjos BL, Nogueira CE, Amaral LA, Weiblen R, Flores EF. An outbreak of orthopoxvirus-associated disease in horses in southern Brazil. J Vet Diagn Invest. 2010;22:143–7. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

Figures

Cite This ArticleRelated Links

Table of Contents – Volume 17, Number 10—October 2011

| EID Search Options |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Please use the form below to submit correspondence to the authors or contact them at the following address:

Clarissa R. Damaso, Instituto de Biofísica Carlos Chagas Filho, Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, Av. Carlos Chagas Filho, 373-CCS, Ilha do Fundão, 21941-590, Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brazil

Top