Volume 22, Number 8—August 2016

Synopsis

Co-infections in Visceral Pentastomiasis, Democratic Republic of the Congo

Figure 4

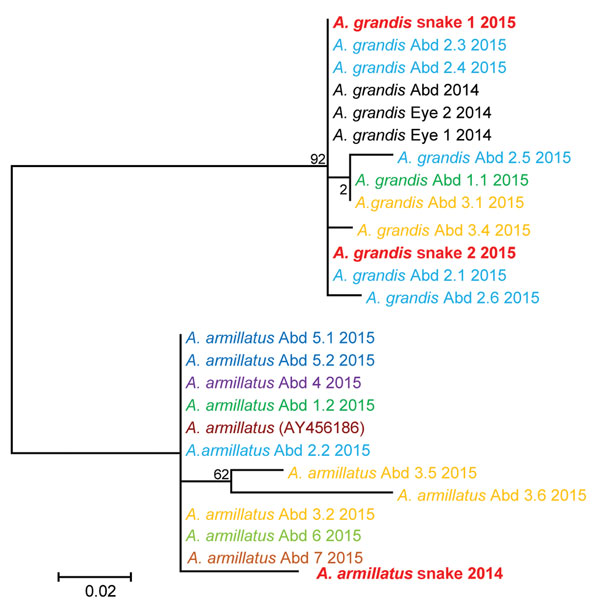

Figure 4. Molecular phylogenetic analysis of Armillifer spp. sequences obtained from humans and snakes in Sankuru District, Democratic Republic of the Congo, 2014–2015. Parasite cytochrome oxidase subunit I gene sequences from abdominal (Abd) surgery patient specimens (larval parasites) and from snake meats for sale at local markets (adult parasites) are shown. Human cases are numbered according to the patient and cyst numbers shown in the Table. Sequences obtained from the same patient share the same color. A GenBank reference sequence (A. armillatus AY456186) is included, as are sequences from the human abdominal and eye infections from the same region of the Democratic Republic of the Congo investigated in 2014 (8,12). The evolutionary history was inferred by using the maximum-likelihood method based on the Hasegawa-Kishino-Yano model. The tree with the highest log likelihood (−646.8057) is shown. The percentage of trees in which the associated taxa clustered together is shown next to the branches. Initial tree(s) for the heuristic search were obtained automatically by applying neighbor-joining and BioNJ algorithms to a matrix of pairwise distances estimated using the maximum composite likelihood approach, and then selecting the topology with superior log likelihood value. Codon positions included were 1st+2nd+3rd+Noncoding. A. grandis and A. armillatus sequences form their own respective branches. Scale bar indicates number of substitutions per site.

References

- Tappe D, Büttner DW. Diagnosis of human visceral pentastomiasis. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2009;3:e320. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Tappe D, Haeupler A, Schäfer H, Racz P, Cramer JP, Poppert S. Armillifer armillatus pentastomiasis in African immigrant, Germany. Emerg Infect Dis. 2013;19:507–8. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Tappe D, Meyer M, Oesterlein A, Jaye A, Frosch M, Schoen C, Transmission of Armillifer armillatus ova at snake farm, The Gambia, West Africa. Emerg Infect Dis. 2011;17:251–4. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Lavrov DV, Brown WM, Boore JL. Phylogenetic position of the Pentastomida and (pan)crustacean relationships. Proc Biol Sci. 2004;271:537–44. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Paré JA. An overview of pentastomiasis in reptiles and other vertebrates. J Exot Pet Med. 2008;17:285–94. DOIGoogle Scholar

- Hardi R, Sulyok M, Rózsa L, Bodó I. A man with unilateral ocular pain and blindness. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;57:469–70. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Sulyok M, Rózsa L, Bodó I, Tappe D, Hardi R. Ocular pentastomiasis in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014;8:e3041. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Lavarde V, Fornes P. Lethal infection due to Armillifer armillatus (Porocephalida): a snake-related parasitic disease. Clin Infect Dis. 1999;29:1346–7. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Latif B, Omar E, Heo CC, Othman N, Tappe D. Human pentastomiasis caused by Armillifer moniliformis in Malaysian Borneo. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2011;85:878–81. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Chen SH, Liu Q, Zhang YN, Chen JX, Li H, Chen Y, Multi-host model-based identification of Armillifer agkistrodontis (Pentastomida), a new zoonotic parasite from China. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2010;4:e647. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Tappe D, Sulyok M, Rózsa L, Muntau B, Haeupler A, Bodó I, Molecular diagnosis of abdominal Armillifer grandis pentastomiasis in the Democratic Republic of Congo. J Clin Microbiol. 2015;53:2362–4. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- De Meneghi D. Pentastomes (Pentastomida, Armillifer armillatus Wyman, 1848) in snakes from Zambia. Parassitologia. 1999;41:573–4.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Kelehear C, Spratt DM, O’Meally D, Shine R. Pentastomids of wild snakes in the Australian tropics. Int J Parasitol Parasites Wildl. 2013;3:20–31. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Dollfus RP, Canet J. [Pentastomide; Raillietiella (Heymonsia) hemidactylia M. L. Hett 1934; supposed susceptibility of parasiting man after the therapeutic ingestion of living lizards] [in French]. Bull Soc Pathol Exot. 1954;47:401–8.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Soulange L. Brygoo. Un cas de parasitose erratique cuntanée. Med Trop (Mars). 1952;1:12.

- Fa JE, Currie D, Meeuwig J. Bushmeat and food security in the Congo Basin: linkages between wildlife and people’s future. Environ Conserv. 2003;30:71–8 .DOIGoogle Scholar

- Nzeh DA, Akinlemibola JK, Nzeh GC. Incidence of Armillifer armillatus (pentastome) calcification in the abdomen. Cent Afr J Med. 1996;42:29–31.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Nozais JP, Cagnard V, Doucet J. Pentastomosis. A serological study of 193 Ivorians [in French]. Med Trop (Mars). 1982;42:497–9.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Mouchet R. Note on Porocephalus moniliformis [in French]. Bull Soc Pathol Exot. 1914;7:497–501.

- Pales M, Pouderoux M. The anatomo-pathologic lesions of pneumonias in A.E.F. [in French]. Bull Soc Pathol Exot. 1934;27:45–55.

- Seiffert H. Further findings of Porocephalus moniliformis in Cameroon [in German]. Arch Schiffs u Tropenhyg. 1910;14:506–14.

- Schäffer H. About the occurence of Porocephalus moniliformis in Cameroon [in German]. Arch Schiffs u Tropenhyg. 1912;16:109–13.

- Smith JA, Oladiran B, Lagundoye SB, Lawson EAL, Francis TI. Pentastomiasis and malignancy. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1975;69:503–12 .DOIGoogle Scholar

- Prathap K, Lau KS, Bolton JM. Pentastomiasis: a common finding at autopsy among Malaysian aborigines. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1969;18:20–7.PubMedGoogle Scholar