Volume 23, Number 12—December 2017

Dispatch

Pathogenic Elizabethkingia miricola Infection in Cultured Black-Spotted Frogs, China, 2016

Figure 2

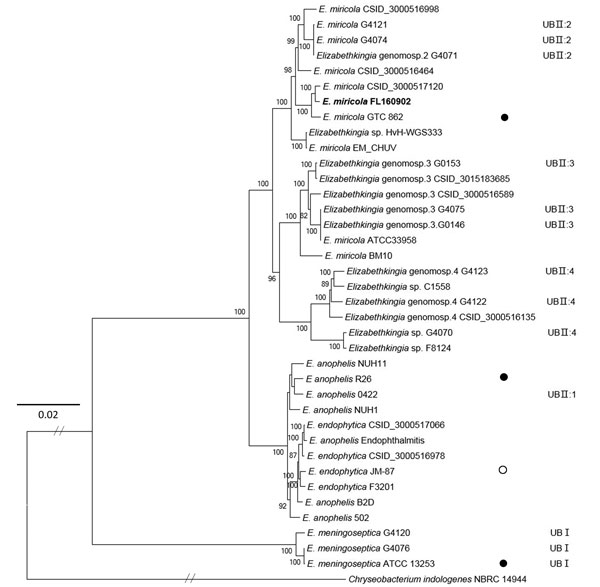

Figure 2. Maximum-likelihood phylogenetic tree of Elizabethkingia miricola FL160902 from an infected frog in Hunan Province, China, and reference genomes. The tree was constructed by using the single-copy orthologous genes of all the 38 genomes with 100 bootstrap replicates. Species identifications strictly followed the National Center for Biotechnology Information submitted names. Isolates assigned into UB groups and subgroups are according to Holmes et al. (12) and Bruun and Ursing (13).Solid circles indicate type strains; open circle indicates a former type strain. Bold indicates strain isolated in this study. Scale bar indicates nucleotide substitutions per site.

References

- Kim KK, Kim MK, Lim JH, Park HY, Lee ST. Transfer of Chryseobacterium meningosepticum and Chryseobacterium miricola to Elizabethkingia gen. nov. as Elizabethkingia meningoseptica comb. nov. and Elizabethkingia miricola comb. nov. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2005;55:1287–93. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Moore LSP, Owens DS, Jepson A, Turton JF, Ashworth S, Donaldson H, et al. Waterborne Elizabethkingia meningoseptica in adult critical care. Emerg Infect Dis. 2016;22:9–17. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Eriksen HB, Gumpert H, Faurholt CH, Westh H. Determination of Elizabethkingia diversity by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry and whole-genome sequencing. Emerg Infect Dis. 2017;23:320–3. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Lau SK, Chow WN, Foo CH, Curreem SO, Lo GC, Teng JL, et al. Elizabethkingia anophelis bacteremia is associated with clinically significant infections and high mortality. Sci Rep. 2016;6:26045. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Perrin A, Larsonneur E, Nicholson AC, Edwards DJ, Gundlach KM, Whitney AM, et al. Evolutionary dynamics and genomic features of the Elizabethkingia anophelis 2015 to 2016 Wisconsin outbreak strain. Nat Commun. 2017;8:15483. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Opota O, Diene SM, Bertelli C, Prod’hom G, Eckert P, Greub G. Genome of the carbapenemase-producing clinical isolate Elizabethkingia miricola EM_CHUV and comparative genomics with Elizabethkingia meningoseptica and Elizabethkingia anophelis: evidence for intrinsic multidrug resistance trait of emerging pathogens. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2017;49:93–7. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Li Y, Kawamura Y, Fujiwara N, Naka T, Liu H, Huang X, et al. Chryseobacterium miricola sp. nov., a novel species isolated from condensation water of space station Mir. Syst Appl Microbiol. 2003;26:523–8. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Green O, Murray P, Gea-Banacloche JC. Sepsis caused by Elizabethkingia miricola successfully treated with tigecycline and levofloxacin. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2008;62:430–2. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Stamatakis A. RAxML version 8: a tool for phylogenetic analysis and post-analysis of large phylogenies. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:1312–3. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Nicholson AC, Humrighouse BW, Graziano JC, Emery B, McQuiston JR. Draft genome sequences of strains representing each of the Elizabethkingia genomospecies previously determined by DNA-DNA hybridization. Genome Announc. 2016;4:e00045-16. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Ursing J, Bruun B. Genetic heterogeneity of Flavobacterium meningosepticum demonstrated by DNA-DNA hybridization. Acta Pathol Microbiol Immunol Scand B. 1987;95:33–9.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Holmes B, Steigerwalt AG, Nicholson AC. DNA-DNA hybridization study of strains of Chryseobacterium, Elizabethkingia and Empedobacter and of other usually indole-producing non-fermenters of CDC groups IIc, IIe, IIh and IIi, mostly from human clinical sources, and proposals of Chryseobacterium bernardetii sp. nov., Chryseobacterium carnis sp. nov., Chryseobacterium lactis sp. nov., Chryseobacterium nakagawai sp. nov. and Chryseobacterium taklimakanense comb. nov. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2013;63:4639–62. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Bruun B, Ursing J. Phenotypic characterization of Flavobacterium meningosepticum strains identified by DNA-DNA hybridization. Acta Pathol Microbiol Immunol Scand B. 1987;95:41–7.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Doijad S, Ghosh H, Glaeser S, Kämpfer P, Chakraborty T. Taxonomic reassessment of the genus Elizabethkingia using whole-genome sequencing: Elizabethkingia endophytica Kämpfer et al. 2015 is a later subjective synonym of Elizabethkingia anophelis Kämpfer et al. 2011. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2016;66:4555–9. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

Page created: November 16, 2017

Page updated: November 16, 2017

Page reviewed: November 16, 2017

The conclusions, findings, and opinions expressed by authors contributing to this journal do not necessarily reflect the official position of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, the Public Health Service, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, or the authors' affiliated institutions. Use of trade names is for identification only and does not imply endorsement by any of the groups named above.