Volume 23, Number 6—June 2017

CME ACTIVITY - Synopsis

Sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease in 2 Plasma Product Recipients, United Kingdom

Cite This Article

Citation for Media

Introduction

In support of improving patient care, this activity has been planned and implemented by Medscape, LLC and Emerging Infectious Diseases. Medscape, LLC is jointly accredited by the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education (ACCME), the Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education (ACPE), and the American Nurses Credentialing Center (ANCC), to provide continuing education for the healthcare team.

Medscape, LLC designates this Journal-based CME activity for a maximum of 1.00 AMA PRA Category 1 Credit(s)™. Physicians should claim only the credit commensurate with the extent of their participation in the activity.

All other clinicians completing this activity will be issued a certificate of participation. To participate in this journal CME activity: (1) review the learning objectives and author disclosures; (2) study the education content; (3) take the post-test with a 75% minimum passing score and complete the evaluation at http://www.medscape.org/journal/eid; and (4) view/print certificate.

Release date: May 12, 2017; Expiration date: May 12, 2018

Learning Objectives

Upon completion of this activity, participants will be able to:

• Recognize the clinical features of 2 cases of sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (sCJD) reported in patients with clotting disorders treated with fractionated plasma products.

• Identify the laboratory and pathology findings of 2 cases of sCJD reported in patients with clotting disorders treated with fractionated plasma product.

• Determine the clinical implications of 2 cases of sCJD reported in patients with clotting disorders treated with fractionated plasma products.

CME Editor

Jude Rutledge, BA, Technical Writer/Editor, Emerging Infectious Diseases. Disclosure: Jude Rutledge has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

CME Author

Laurie Barclay, MD, freelance writer and reviewer, Medscape, LLC. Disclosure: Laurie Barclay, MD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships: owns stock, stock options, or bonds from Alnylam; Biogen; Pfizer.

Authors

Disclosures: Patrick Urwin, MBBS, MA (CANTAB); Kumar Thanigaikumar, MBBS, MRCP, FRCPATH; James W. Ironside, MD; Anna Molesworth, PhD; Patricia E. Hewitt, MD, FRCPATH; Charlotte A. Llewelyn, PhD; and Jan Mackenzie, PG Cert Epidemiology, have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Richard S. Knight, BMBCh, FRCP (E), has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships: served as a speaker or a member of a speakers bureau for Pfizer Inc. Robert G. Will, MD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships: served as an advisor or consultant for LFB (Paris); Ferring Pharmaceuticals.

Abstract

Sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (sCJD) has not been previously reported in patients with clotting disorders treated with fractionated plasma products. We report 2 cases of sCJD identified in the United Kingdom in patients with a history of extended treatment for clotting disorders; 1 patient had hemophilia B and the other von Willebrand disease. Both patients had been informed previously that they were at increased risk for variant CJD because of past treatment with fractionated plasma products sourced in the United Kingdom. However, both cases had clinical and investigative features suggestive of sCJD. This diagnosis was confirmed in both cases on neuropathologic and biochemical analysis of the brain. A causal link between the treatment with plasma products and the development of sCJD has not been established, and the occurrence of these cases may simply reflect a chance event in the context of systematic surveillance for CJD in large populations.

Human prion diseases are a group of rare and fatal neurodegenerative diseases that include idiopathic (sporadic), genetic (inherited), and acquired (infectious) disorders (1). All are associated with the accumulation of an abnormal isoform of the prion protein (PrPSc) in the central nervous system (1). The most common human prion disease is the sporadic form of Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (sCJD), which occurs worldwide with a relatively uniform incidence of 1–2 cases per million population per year, a peak incidence in the 7th decade of life, and a median duration of illness of 4 months. The relatively consistent mortality rates associated with sCJD, the overall random spatial and temporal distribution of cases, and the absence of any confirmed environmental risk factor have led to the hypothesis that sCJD occurs because of the spontaneous generation of PrPSc in the brain (1). In contrast, variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (vCJD) is an acquired disorder that is most likely caused by the consumption of meat or meat products contaminated with the bovine spongiform encephalopathy agent. The median age at death in vCJD is 30 years, with a median duration of illness of 14 months. Most cases of vCJD have occurred in the United Kingdom, which has had the largest epizootic of bovine spongiform encephalopathy in the world. Of the 178 UK vCJD cases, 3 have been identified as cases of secondary transmission caused by the transfusion of nonleukodepleted red blood cell components from vCJD-infected blood donors.

Lookback studies have shown no evidence of transmission through blood transfusion in sCJD (2,3), despite the identification of PrPSc in some peripheral tissues (4) and experimental evidence, which demonstrated infectivity in blood (5) by using intracerebral inoculation of highly sensitive transgenic mice. The absence of clinical cases causally linked to past treatment with fractionated plasma products has been used as evidence of the safety of these products in relation to sCJD (6). These products are generally manufactured from the pooled plasma from several thousand donors; production using UK plasma was discontinued in 1999.

We describe 2 cases of sCJD in patients who had previously received treatment with UK plasma–sourced plasma products; both patients had been informed that they were at increased risk for vCJD because of that treatment. The clinical features and investigations in these cases were typical of sCJD; the neuropathologic diagnosis in both cases was sCJD (subtype MM1).

The UK National CJD Research and Surveillance Unit has been carrying out systematic epidemiologic study of CJD since 1990. The methodology of this study has been published previously (7). In brief, patients with suspected CJD are referred by clinicians and visited by a research registrar, who obtains details of the clinical history and investigations, information on a range of possible risk factors, and past medical history. The Transfusion Medicine Epidemiology Review study investigates potential links between donors and recipients of labile blood components and, in cases of sCJD, investigates patients who have a history of blood donation or having received a blood transfusion.

Coordinated surveillance of CJD has been undertaken in the European Union since 1993 (8). National surveillance programs for CJD also are in place in several other countries, including Australia, Canada, Japan, and the United States.

Case 1

In 2014, a 64-year-old woman suffered a rapidly progressive dementia with deterioration in driving skills and balance disturbance, then limb coordination deficits with handwriting impairment. In the second month, her gait deteriorated, becoming shuffling and unsteady, she struggled to dress herself, and she had onset of daytime hypersomnolence. She became distractible, had visual misperceptions, emotional lability, and spatial memory problems. She was hospitalized at the beginning of the third month of her illness and had onset of cortical blindness, myoclonus, and akinetic mutism. She experienced rapid decline and died after a total illness duration of 3 months.

An electroencephalogram performed during the final stages of illness showed background slowing and runs of periodic complexes, and a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) brain scan showed high signal in the caudate heads with posterior cortical ribboning. A cerebral spinal fluid (CSF) 14–3–3 assay and real-time quaking-induced conversion test for PrPSc both were positive. Prion protein gene (PRNP) sequencing showed no mutations with methionine homozygosity at codon 129.

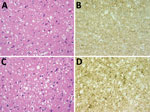

Postmortem examination of the brain showed widespread spongiform encephalopathy of predominantly microvacuolar type. Immunocytochemistry for prion protein gave a widespread positive reaction in a granular/synaptic pattern (Figure). No plaques or plaque-like structures were identified. Results of immunocytochemistry for disease-associated prion protein were negative in peripheral nerve, liver, lymph node, appendix, and spleen. Western blot analysis of frontal cortex and cerebellum confirmed the presence of protease-resistant prion protein with a type 1A isoform.

The patient had been diagnosed with von Willebrand disease in childhood. Her early therapies include numerous transfusions of red blood cells and platelets; in more recent years, she received plasma-derived and recombinant factor VIII and additional blood component transfusions at times of hemorrhage. Factor VIII was administered on 4 occasions in the 1990s and during 2000–2004 and von Willebrand factor/factor VIII (Haemate-P) during 2001–2013. Because of her history of exposure to UK-sourced plasma products, for public health purposes she had been informed that she was at risk for vCJD, although she was not known to have been exposed to factor VIII derived from a batch including a vCJD donation. She had no history of potential iatrogenic exposure to CJD and no family history of CJD.

Donors for all blood or platelet transfusions since 2001 have been identified. Of the 107 donors, 106 are still alive, with a median age of 55 years (range 27–80 years). (Table 1). One donor of leukodepleted platelets, which were transfused 12 years before clinical onset in the recipient, died in 2013 at 76 years of age, and the diagnoses on the death certificate were vascular dementia and bladder cancer. Identification of donors for transfusions before 2001 has not been possible.

Case 2

In 2014, a 64-year-old woman reported day/night reversal of sleep patterns and, 3 months later, excessive tearfulness, for which she was started on antidepressants. She then had onset of writing problems, followed during the next few days by increasing language problems that led to expressive dysphasia. She deteriorated rapidly thereafter, requiring assistance with her activities of daily living and having coordination and memory problems, jerking movements suggestive of myoclonus, and itching in both arms. She was admitted to the hospital and experienced a probable focal seizure with secondary generalization. She had onset of a homonymous hemianopia and limb rigidity and then became bedbound and mute, dying 7 months after the onset of symptoms.

An electroencephalogram performed during the final stages of illness showed widespread slowing, more evident on the left. An MRI brain scan showed left-sided caudate head and anterior putaminal high signal. Diffusion weighted imaging showed areas of cortical high signal. Results of a CSF 14–3–3 assay and real-time quaking-induced conversion tests were positive. Consent for full sequencing of the PRNP was not obtained; methionine homozygosity at codon 129 was identified.

Postmortem neuropathologic examination of the brain showed a widespread spongiform encephalopathy with microvacuolar spongiform change, neuronal loss, and gliosis. Immunostaining for prion protein showed widespread positivity with a granular/synaptic pattern (Figure). No amyloid plaques were identified. Western blot analysis confirmed the presence of protease resistant prion protein with a type 1A isoform. There was no evidence of abnormal prion protein accumulation in spleen and appendix either on immunocytochemistry or high sensitivity Western blot analysis.

The patient was known to have hemophilia B since 1964 and had received plasma-derived and recombinant factor IX during 1984–2012. For public health purposes, she had been informed that she was at risk for vCJD and in 1991 had received factor IX derived from a pool containing plasma from a donor who subsequently had vCJD. She had no history of potential iatrogenic exposure to CJD and no family history of CJD.

In 1985, the patient received 6 units of fresh frozen plasma (FFP). Tracing of donors has not been possible.

This report describes 2 cases of sCJD in patients with a history of treatment with UK-sourced plasma products, 1 with a history of hemophilia B and 1 with von Willebrand’s disease. To our knowledge, no previous case of sCJD in a person with a history of extended exposure to plasma products has been reported. It is clearly of concern that there have been 2 such cases in a relatively short period in the UK, where many plasma product recipients have been informed that they are at increased risk for vCJD. However, a causal link between the treatment with plasma products and the onset of sCJD has not been established, and the occurrence of these cases may simply reflect a chance event in the context of systematic surveillance of CJD in large populations.

Both patients had been informed that they were at increased risk for vCJD, and considering the evidence for the type of CJD in the 2 cases is important. Both patients had a clinical phenotype suggestive of sCJD, including a short duration of illness, typical early symptoms, a suggestive MRI scan, and, in 1 patient, a typical EEG. Notably, both patients had a positive real-time quaking-induced conversion test result for PrPSc in CSF; previously this test had not been positive in any case of vCJD evaluated in our laboratory (Table 2) (9). However, neuropathological examination was critical; it showed appearances typical of sCJD in both patients and no evidence of peripheral pathogenesis on immunostaining of lymphoreticular tissues, a feature that is observed in all tested specimens of vCJD patients to date (10). Furthermore, both patients had a type 1A isoform PrPSc on Western blot consistent with a diagnosis of sCJD subtype MM1 (11). Neither patient had a history of potential iatrogenic exposure or a family history of CJD, and for the case for which sequencing of the PRNP was performed, no mutations were detected. In both cases, an MM genotype occurred at codon 129 of PRNP, which does not distinguish between sCJD and vCJD. Laboratory transmission studies to provide evidence of agent strain in the cases have not been possible.

One patient had received multiple transfusions of blood components over an extended period, and the other had received 6 units of FFP 19 years before clinical onset, raising the possibility that these cases could have resulted from secondary transmission through blood components. In the case of the patient with von Willebrand disease, 107 donors have been traced, and none appear in the register of cases of CJD kept at the National CJD Research and Surveillance Unit. However, it has not been possible to obtain information on blood transfusions for this patient before 2001 nor on the FFP transfusions for the patient with hemophilia B. Lookback studies in the United States and United Kingdom have provided no evidence of transfusion-transmission of sCJD (2,3), and although 1 study suggested an increase in risk after a lag period of 10 years (12), this finding was not confirmed in another study (13). The balance of evidence indicates that, if sCJD is transmitted by blood transfusion, it must be a rare event, if it happens at all, and transfusion transmission is probably not the explanation for the 2 cases we describe.

Systematic surveillance for CJD, including a coordinated study in Europe (14), has been carried out in many countries over the past 25 years and is continuing. Many of these studies obtain information on potential risk factors, including details of past medical history. To date, no case of sCJD has been reported in a person who has received treatment for a clotting disorder. In fact, the absence of such a case has been used to argue against the possibility that plasma-derived products pose a risk for sCJD transmission (6). CJD surveillance centers are aware of the relevance of this issue, and sCJD patients with a history of treatment with plasma products probably would have been identified and reported if they occurred. Although it is surprising that 2 cases of sCJD have been identified among a population of 4,000–5,000 patients in the UK who have been treated for clotting disorders with fractionated plasma products, the total population under surveillance for CJD in Europe and internationally exceeds 500 million. Assuming an annual incidence rate of sCJD of 1.5–2.0 per million population (15), the occurrence of 2 cases of sCJD in this total population may not imply a causal link between the treatment and the occurrence of the disease. The 2 cases were identified over a period of months, and no further cases have been found since 2014; however, continuing to search for such cases through CJD surveillance programs is essential.

Dr. Urwin worked as a research registrar at the National CJD Research and Surveillance Unit and is currently training in neurology. His primary research interests include human prion diseases.

Acknowledgments

We thank Mark W. Head for the Western blot data.

The National CJD Research and Surveillance Unit is supported by the Policy Research Program of the Department of Health and the Government of Scotland (grant no. PR-ST-0614-00008). This report is independent research in part funded by the Department of Health Policy Research Programme and the Government of Scotland. The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Department of Health or the Government of Scotland.

References

- Prusiner SB. Molecular biology of prion diseases. Science. 1991;252:1515–22. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Dorsey K, Zou S, Schonberger LB, Sullivan M, Kessler D, Notari E IV, et al. Lack of evidence of transfusion transmission of Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease in a US surveillance study. Transfusion. 2009;49:977–84. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Urwin PJ, Mackenzie JM, Llewelyn CA, Will RG, Hewitt PE. Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease and blood transfusion: updated results of the UK Transfusion Medicine Epidemiology Review Study. Vox Sang. 2016;110:310–6. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Glatzel M, Abela E, Maissen M, Aguzzi A. Extraneural pathologic prion protein in sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:1812–20. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Douet JY, Zafar S, Perret-Liaudet A, Lacroux C, Lugan S, Aron N, et al. Detection of infectivity in blood of persons with variant and sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. Emerg Infect Dis. 2014;20:114–7. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- European Medicines Agency. CHMP position statement on Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease and plasma-derived and urine-derived medicinal products. London, 23 June 2011 [cited 2015 May 1]. http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Position_statement/2011/06/WC500108071.pdf

- Cousens SN, Zeidler M, Esmonde TF, De Silva R, Wilesmith JW, Smith PG, et al. Sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease in the United Kingdom: analysis of epidemiological surveillance data for 1970-96. BMJ. 1997;315:389–95. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Wientjens DPWM, Will RG, Hofman A. Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease: a collaborative study in Europe. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1994;57:1285–99.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- McGuire LI, Peden AH, Orrú CD, Wilham JM, Appleford NE, Mallinson G, et al. Real time quaking-induced conversion analysis of cerebrospinal fluid in sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. Ann Neurol. 2012;72:278–85. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Head MW, Ritchie D, Smith N, McLoughlin V, Nailon W, Samad S, et al. Peripheral tissue involvement in sporadic, iatrogenic, and variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease: an immunohistochemical, quantitative, and biochemical study. Am J Pathol. 2004;164:143–53. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Head MW, Bunn TJR, Bishop MT, McLoughlin V, Lowrie S, McKimmie CS, et al. Prion protein heterogeneity in sporadic but not variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease: UK cases 1991-2002. Ann Neurol. 2004;55:851–9. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Puopolo M, Ladogana A, Vetrugno V, Pocchiari M. Transmission of sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease by blood transfusion: risk factor or possible biases. Transfusion. 2011;51:1556–66. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Molesworth AM, Mackenzie J, Everington D, Knight RSG, Will RG. Sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease and risk of blood transfusion in the United Kingdom. Transfusion. 2011;51:1872–3, author reply 1873–4 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Ladogana A, Puopolo M, Croes EA, Budka H, Jarius C, Collins S, et al. Mortality from Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease and related disorders in Europe, Australia, and Canada. Neurology. 2005;64:1586–91. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Minikel EV, Vallabh SM, Lek M, Estrada K, Samocha KE, Sathirapongsasuti JF, et al.; Exome Aggregation Consortium (ExAC). Quantifying prion disease penetrance using large population control cohorts. Sci Transl Med. 2016;8:322ra9. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

Figure

Tables

Follow Up

Earning CME Credit

To obtain credit, you should first read the journal article. After reading the article, you should be able to answer the following, related, multiple-choice questions. To complete the questions (with a minimum 75% passing score) and earn continuing medical education (CME) credit, please go to http://www.medscape.org/journal/eid. Credit cannot be obtained for tests completed on paper, although you may use the worksheet below to keep a record of your answers.

You must be a registered user on http://www.medscape.org. If you are not registered on http://www.medscape.org, please click on the “Register” link on the right hand side of the website.

Only one answer is correct for each question. Once you successfully answer all post-test questions, you will be able to view and/or print your certificate. For questions regarding this activity, contact the accredited provider, CME@medscape.net. For technical assistance, contact CME@medscape.net. American Medical Association’s Physician’s Recognition Award (AMA PRA) credits are accepted in the US as evidence of participation in CME activities. For further information on this award, please go to https://www.ama-assn.org. The AMA has determined that physicians not licensed in the US who participate in this CME activity are eligible for AMA PRA Category 1 Credits™. Through agreements that the AMA has made with agencies in some countries, AMA PRA credit may be acceptable as evidence of participation in CME activities. If you are not licensed in the US, please complete the questions online, print the AMA PRA CME credit certificate, and present it to your national medical association for review.

Article Title:

Sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease in 2 Plasma Product Recipients, United Kingdom

CME Questions

1. Your patient is a 62-year-old woman with a long history of clotting disorder and recent onset of rapidly progressive dementia with prominent motor features. According to the case reports by Urwin and colleagues, which of the following statements about the clinical features of 2 cases of sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (sCJD) reported in patients with clotting disorders treated with fractionated plasma products is most accurate?

A. Course was rapidly progressive with symptoms including incoordination, shuffling gait, seizure, daytime hypersomnolence, myoclonus, emotional lability, dysphasia, and limb rigidity

B. Vision was unaffected

C. One patient had a history of potential iatrogenic exposure, and the other had a family history of CJD

D. Survival duration from time of onset was roughly 1 year

2. According to the case reports by Urwin and colleagues, which of the following statements about the laboratory and pathology findings of 2 cases of sCJD reported in patients with clotting disorders treated with fractionated plasma products is correct?

A. Cerebrospinal fluid real-time quaking-induced conversion (CSF RT-QuIC) was positive in only 1 patient

B. Neuropathology was typical for sCJD in both patients, and neither had evidence of peripheral pathogenesis on immunostaining of lymphoreticular tissues as is seen in variant CJD (vCJD)

C. Both patients had an MM genotype at codon 129 of PRNP, proving the diagnosis of sCJD

D. Only 1 patient had a type 1A isoform PrPSc on Western blot

3. According to the case reports by Urwin and colleagues, which of the following statements about the clinical implications of 2 cases of sCJD reported in patients with clotting disorders treated with fractionated plasma products is correct?

A. The study proves that treatment with plasma products causes sCJD

B. Look-back studies in the United States and United Kingdom have shown transfusion-transmission of sCJD

C. Plasma-derived products pose no risk for sCJD transmission

D. It is essential to continue to search for cases of transfusion-transmission of sCJD through CJD surveillance programs

Activity Evaluation

|

1. The activity supported the learning objectives. |

||||

|

Strongly Disagree |

|

|

|

Strongly Agree |

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

|

2. The material was organized clearly for learning to occur. |

||||

|

Strongly Disagree |

|

|

|

Strongly Agree |

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

|

3. The content learned from this activity will impact my practice. |

||||

|

Strongly Disagree |

|

|

|

Strongly Agree |

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

|

4. The activity was presented objectively and free of commercial bias. |

||||

|

Strongly Disagree |

|

|

|

Strongly Agree |

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

Related Links

Table of Contents – Volume 23, Number 6—June 2017

| EID Search Options |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Please use the form below to submit correspondence to the authors or contact them at the following address:

R.G. Will, National CJD Research and Surveillance Unit, Western General Hospital, Edinburgh, Scotland EH4 2XU, UK

Top