Volume 24, Number 1—January 2018

Dispatch

Serologic Evidence of Fruit Bat Exposure to Filoviruses, Singapore, 2011–2016

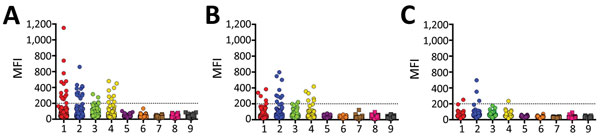

Figure 1

Figure 1. Mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) values obtained from Bio-Plex assay (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) screening of individual serum samples from bats of 3 species with soluble filovirus glycoproteins. Dashed line indicates the cutoff value at 200 MFI. 1, Zaire ebolavirus; 2, Bundibugyo ebolavirus; 3, Taï Forest ebolavirus; 4, Sudan ebolavirus; 5, Reston ebolavirus–monkey; 6, Reston ebolavirus–pig; 7, Marburg virus–Musoke; 8, Marburg virus–Angola; 9, Ravn virus.

1These authors contributed equally to this article.

Page created: December 19, 2017

Page updated: December 19, 2017

Page reviewed: December 19, 2017

The conclusions, findings, and opinions expressed by authors contributing to this journal do not necessarily reflect the official position of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, the Public Health Service, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, or the authors' affiliated institutions. Use of trade names is for identification only and does not imply endorsement by any of the groups named above.