Volume 24, Number 3—March 2018

Research

Emergence of Streptococcus pneumoniae Serotype 12F after Sequential Introduction of 7- and 13-Valent Vaccines, Israel

Cite This Article

Citation for Media

Abstract

Israel implemented use of 7- and 13-valent pneumococcal vaccine in 2009 and 2010, respectively. We describe results of prospective, population-based, nationwide active surveillance of Streptococcus pneumoniae serotype 12F (Sp12F) invasive pneumococcal disease (IPD) dynamics in the 7 years after vaccine introduction. Of 4,573 IPD episodes during July 2009–June 2016, a total of 434 (9.5%) were caused by Sp12F. Sp12F IPD rates (cases/100,000 population) increased in children <5 years of age, from 1.44 in 2009–2010 to >3.9 since 2011–2012, followed by an increase in all ages. During 2011–2016, Sp12F was the most prevalent IPD serotype. Sp12F isolates were mostly penicillin nonsusceptible (MIC >0.06 µg/mL; MIC50 = 0.12) and predominantly of sequence type 3774), a clone exclusively found in Israel (constituting ≈90% of isolates in 2000–2009). The sharp increase, long duration, and predominance of Sp12F IPD after vaccine implementation reflect a single clone expansion and may represent more than a transient outbreak.

Streptococcus pneumoniae is a leading cause of illness and death worldwide; the highest incidence occurrs in children <2 years of age and in the elderly (1–5). For this reason, pneumococcal diseases are a target for global immunization programs in children and adults (1,6,7). Most reported cases of invasive pneumococcal disease (IPD) are sporadic, and outbreaks occur infrequently (5). Reported outbreaks have been of limited epidemiologic significance and associated with specific serotypes, including Streptococcus pneumoniae serotype 12F (Sp12F) (5,8,9).

Since the introduction of pneumococcal conjugated vaccine (PCV), a substantial increase in nasopharyngeal carriage of nonvaccine serotypes (NVT) has been observed in surveillance studies (10–14) and randomized trials assessing the effect of PCV on NVT carriage, comparing vaccinated children and unvaccinated controls (10). This increase in NVT carriage, commonly referred to as the replacement phenomenon, was accompanied by an increase in rates of IPD caused by NVT, diminishing the overall impact of PCVs on IPD rates (10,11).

In Israel, the 7-valent PCV (PCV7) was introduced to the national immunization plan (NIP) in July 2009, with a catch-up plan for children <2 years of age, and was gradually replaced with the 13-valent PCV (PCV13) in November 2010, without further catch-up. Uptake rates were high (>90%) (14). PCV7/PCV13 sequential introduction was followed by a substantial decline in overall IPD incidence among all age groups, driven mainly by the near-elimination of vaccine serotype disease, but accompanied by a substantial increase in IPD caused by non-PCV13 serotypes (15,16).

Sp12F is a nonvaccine serotype that is uncommonly carried in healthy persons (12,13,17). Sp12F was relatively rare in Israel among IPD cases in the pre-PCV era but has increased noticeably following PCV introduction (15). This serotype has been associated with outbreaks of community-acquired pneumonia and IPD in the United States (17–20) and Canada (8,21). Globally, most reported Sp12F isolates were of sequence type (ST) lineages ST989 and ST218 (17,18,22,23). An outbreak clone in Canada has been reported to have acquired resistance to macrolides and fluoroquinolones, replacing susceptible clones (21), but in general Sp12F is penicillin susceptible.

We assessed the dynamics of Sp12F IPD rates after sequential introduction of PCV7/PCV13 in Israel. Additionally, we investigated the molecular and antimicrobial drug susceptibility characteristics of these serotype isolates before and after vaccine introduction.

Study Design

Our data derive from ongoing nationwide, prospective, population-based, active surveillance on IPD in children and adults in Israel (15,16). This report concentrates on data collected during the 7 years that followed PCV introduction in Israel (July 2009–June 2016). The study was conducted in all 27 medical health centers routinely obtaining cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and blood cultures from children and adults: 26 hospitals and 1 major outpatient health maintenance organization. Less than 1% of blood cultures and no CSF cultures were obtained outside these centers. This setting enabled us to cover all culture-confirmed IPD cases among the population of Israel (15).

IPD isolates are sent regularly to the national reference center at the Central Laboratories of the Ministry of Health in Jerusalem for confirmation and serotyping (15,16). Since 2009, active surveillance on IPD in all ages has been conducted in all 27 laboratories performing blood cultures in Israel. The capture–recapture method ensured the reporting of >95% of cases. Using these data, we completed the isolates missing from the passive surveillance system, so that all S. pneumoniae isolates from blood, CSF, or both collected during the relevant period in Israel were included in this study. Eventually, S. pneumoniae strains from 4,573 IPD cases, isolated from blood or CSF, were included in the study. The population breakdown during the study period is given in Table 1. During this period, the Jewish population was ≈79% of the total population (24).

Case Definition

We defined an IPD episode by isolation of S. pneumoniae from blood or CSF. We excluded positive cultures from sterile sites other than blood or CSF (i.e., joint/pleural fluid or peritoneal fluid) (15,16), as well as diagnoses based solely on nonculture methods (PCR, antigen testing, Gram stain, or clinical diagnosis only).

Vaccine Uptake

The method of evaluating vaccine uptake initiated in July 2009 has been described elsewhere (14,15). In June 2009, the proportion of children 12–23 months of age who received >2 of any PCV doses was 20%; this proportion increased to 71% in June 2010 and has increased to ≈95% since 2011.

Bacteriology

We inoculated S. pneumoniae cultures onto tryptic soy agar plates supplemented with 5% defibrinated sheep blood (Hy-labs, Rehovot, Israel) and incubated them at 37°C for 24 hours in a 5% enriched CO2 atmosphere. Identification of S. pneumoniae was done as previously described (15).

Serotypes

All strains were serotyped by the Quellung test; since 2013, the serotype has been determined by a validated combination of the capsular sequence typing molecular typing protocol and serotyping using the antisera of Statens Serum Institute (Copenhagen, Denmark). Serotype 6A was differentiated from serotype 6C by PCR (10).

Antimicrobial Drug Susceptibility Testing

We determined susceptibility to penicillin for Sp12F strains by the oxacillin disk diffusion screening method of Bauer and Kirby and Etest (BioMérieux, Marcy l’Étoile, France) according to Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) guidelines (25). Because Sp12F often causes meningitis, we set the susceptibility cutoff values according to the CLSI cutoff for meningitis. Thus, we defined isolates with penicillin MICs of <0.06 μg/mL as susceptible to penicillin and considered those with MICs >0.06 μg/mL to be nonsusceptible.

Pulsed-Field Gel Electrophoresis

We determined the genetic relatedness for all IPD strains isolated since 2009 and all Sp12F strains isolated during 2000–2008 available in our strains bank. We prepared and analyzed chromosomal DNA fragments generated by SmaI digestion as described previously (11,26,27), with modifications.

We performed genotype analysis and clustering using the Bionumerics version 7.6 software package (Applied-Maths, Sint-Martens-Latem, Belgium) with dice coefficients, a 1% position tolerance, and optimization values. We performed cluster analysis by the unweighted pair-group mean analysis. All isolates in the same cluster, defined as clonal, were assigned a letter, A to T, for analysis purposes.

Multilocus Sequence Typing

We characterized selected isolates representing pulsed-field gel electrolysis (PFGE) cluster and isolate years by multilocus sequence typing (MLST). The 7 housekeeping loci (aroE, ddl, gdh, gki, recP, spi, and xpt) were amplified according to the S. pneumoniae PubMLST (28). We crudely extracted bacterial cells by boiling and performed PCR and sequencing by using a revised protocol provided by Bruno Pichon (Antimicrobial Resistance and Healthcare Associated Infection Unit, Public Health England, pers. comm., 2016 Sept 16).

We designed new primers for allele amplification and sequencing. These primers do not contain degenerative bases; an M13 tag on each 5′ primer sequence was added to ease sequencing setup (Table 2). Sequencing of the forward and reverse amplicons was performed at the Center for Genomic Technologies, Institute of Life Sciences, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem (Jerusalem, Israel), using BigDye Terminator v1.1 chemistry (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA).

Genomic Data Analysis

We performed genomic data analysis for capsular sequence typing, PFGE, and MLST using Bionumerics version 7.6 software (Applied Maths). We retrieved MLST allelic profiles and STs from the S. pneumoniae MLST database (29) and submitted the new alleles and STs to the database curator for ST assignment. We compared MLST data with all Sp12F strains submitted to PubMLST.

Statistical Analysis

We performed statistical analysis using SPSS version 14.0 software for Windows (IBM SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). A p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

The data from the active surveillance during 2009–2016 are presented according to epidemiologic years, July through June. Each isolate was counted only once per episode; episodes were separated by >30 days for the same serotype or by any interval for different serotypes. Rate reductions and ratios were calculated. The following age groups were defined: <5 years, 5–17 years, 18–64 years, and ≥65 years of age.

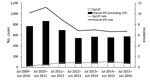

During the study, we identified 4,573 IPD episodes (93% bacteremia and 7% meningitis). Of those, 434 (9.5%) were caused by serotype 12F (Figure 1).

Study Population Characteristics

Patients <5 years of age accounted for 27% of the overall study population; those 5–17 years of age, 8%; those 18–64 years of age, 31%; and those ≥65 years of age, 34%. Overall, 56.3% of all episodes occurred in male patients, and 86.4% of all episodes occurred among the Jewish population.

Overall IPD

We ompared the first (2009–2010) and the last (2015–2016) study years and found that overall IPD rates (cases/100,000 population) declined by 34% (incidence rate ratio [IRR] 0.66, 95% CI 0.59–0.74), from 10.2 to 6.7 (Figure 1). IPD rates substantially declined in all age groups but most notably in children <5 years of age (48% rate reduction, from 30.9 to 16.1 cases/100,000 population). The results for the first study year (2009–2010) already showed a substantial reduction compared with the pre-PCV period (15,16) (Figure 1).

IPD Caused by PCV13 Serotypes

Rates of IPD caused by PCV13 serotypes and proportions of all IPD episodes declined substantially throughout the study period. Rates (cases/100,000 population) of IPD caused by PCV7 serotypes declined by 90%, from 2.6 to 0.5, from the first to the last study years. Similarly, rates of IPD caused by PCV13 serotypes declined by 80%, from 7.4 to 1.5, during the study period.

Proportions of all IPD episodes caused by PCV7 serotypes substantially declined by 74%, from 24.8% in 2009–2010 to 6.4% in 2015–2016. Proportions of all IPD episodes caused by PCV13 serotypes decreased by 68%, from 69.4% to 22.4%.

IPD Caused by Non-PCV13 Serotypes

IPD caused by non-PCV13 serotypes increased by 93%. Rates (cases/100,000 population) increased from 2.8 in 2009–2010 to 5.4 in 2015–2016.

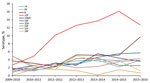

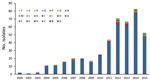

Sp12F

We observed a steady increase (except for the last study year) in the proportion of Sp12F out of all IPD episodes throughout the study: 2.7% in 2009–2010, 4.9% in 2010–2011, 10.1% in 2011–2012, 12.6% in 2012–2013, 13.7% in 2013–2014, 16.1% in 2014–2015, and 12.7% in 2015–2016 (Figure 2; Table 1). The incidence of IPD (in all ages) caused by Sp12F increased over the same period except for 1 slight decrease: 0.26 in 2009–2010, 0.53 in 2010–2011, 0.88 in 2011–2012, 0.85 in 2012–2013, 0.95 in 2013–2014, 1.05 in 2014–2015, and 0.83 in 2015–2016. Similar trends were observed in all age groups, with the sharpest increase observed in children <5 years of age, for which the respective figures by year were 1.44, 2.17, 4.72, 4.37, 5.70, 3.94, and 4.74 (Figure 3). Of note, 91.7% of all Sp12F episodes occurred in the Jewish population.

Analysis of Sp12F Isolates

To assess the association between PCV7/PCV13 introduction and the dynamics of Sp12F rates, we analyzed strains isolated during 2000–2015. Overall, we analyzed 445 Sp12F strains by PFGE (Figure 4). The isolate population consists of a predominant pulsotype (A; 90.1% of isolates), and several other diverse pulsotypes (Figure 5). The predominant pulsotype was observed throughout the study period and was consistently prevalent among the Sp12F population; thus, the observed more general serotype Sp12F increase following PCV7/PCV13 introduction can be attributed to an expansion of this single clone during the study period.

MLST of Sp12F

We further analyzed representative Sp12F isolates by MLST. Among 25 isolates with the predominant PFGE pulsotype, 24 were typed as ST3774 and 1 as the closely related ST3524. Four isolates from other PFGE pulsotypes were typed as ST989 and 1 isolate from another PFGE pulsotype was typed as ST3377.

We compared the MLST type with isolates reported as Sp12F in the global PubMLST database (29). This database contains 283 isolates serotyped as Sp12F and 105 sequence types. Among these isolates, the most common STs are ST218 and ST989, as previously published (17,18,22,23) (Figure 6). ST3774 is rare among isolates submitted to this global database, with only 1 isolate reported from Israel in 2006.

Antimicrobial Drug Resistance of Sp12F

Among all Sp12F isolates, 89% were penicillin nonsusceptible (MIC >0.06); nonsusceptibility rates varied by year from 70% to 99% (MIC50 0.12 μg/mL, range 0.02–1.2 μg/mL). However, most strains were fully susceptible to ceftriaxone (99%; MIC50 0.06 μg/mL, range 0.02–1.0 μg/mL), clindamycin (95%), rifampin (100%), and vancomycin (100%).

S. pneumoniae serotype 12F, a non-PCV13 serotype, is currently the most prevalent pneumococcal serotype causing IPD in Israel. This previously rare serotype caused 434 IPD cases during July 2009–June 2016 and became prevalent in all age groups, most distinctly in young children. The population of Sp12F during 2000–2016 was >90% of the same clonal complex according to PFGE and MLST analyses, indicating the expansion of the ST3774 sequence type, which is currently unique to Israel. The predominant global Sp12F outbreak clones ST218 and ST989 (21) are very rare in IPD cases in Israel.

Sp12F was previously reported to have high invasive disease potential and is sometimes called hyperinvasive (8,30–32). It was reported as the most common serotype causing IPD in Japan (31,32), and it has been the cause of an IPD outbreak in Canada (8). Furthermore, several sites reported high disease potential for meningitis with Sp12F (30,33), and several Sp12F outbreaks have been reported in the literature among closed or crowded populations (18,34), including daycare centers (35), military groups (34), a jail (20), and a homeless shelter (36).

In a recent study from France that evaluated the invasive potential of specific serotypes and compared nasopharyngeal carriage in healthy children to carriage in children infected with IPD, Sp12F was shown to be a major cause of IPD but was not found in nasopharyngeal cultures (30). Furthermore, in Israel, Sp12F was rarely found in carriage studies before and after vaccination trials (14,37,38). These findings emphasize both the invasive nature of Sp12F and its failure to become a successful colonizer.

The emergence of IPD caused by Sp12F in Israel, mainly by clonal expansion, may be attributed, at least in part, to the observed more general serotype replacement after PCV implementation. The emergence of this serotype in the youngest age groups after PCV7/PCV13 introduction supports this hypothesis. However, the previously reported low carriage rate of Sp12F may counter this possibility, and current data on Sp12F carriage in Israel are needed to support this theory. Alternatively, a large-scale clonal outbreak, of long duration and high invasiveness rather than true replacement, may be at the origin of this serotype emergence.

Our results emphasize the role of Sp12F as a serious current public health challenge. Continued monitoring of IPD and specific serotype distribution are needed to enable the development of future vaccination strategies. The evolutionary origin of this emerging clone will be further studied by whole genome sequencing, which may offer insights into the virulence of Sp12F strains.

Dr. Rokney is head of the National Reference Centers at the Government Central Laboratories of the Israel Ministry of Health, Jerusalem. His research interests include molecular typing and epidemiology of infectious diseases.

Acknowledgment

References

- O’Brien KL, Wolfson LJ, Watt JP, Henkle E, Deloria-Knoll M, McCall N, et al.; Hib and Pneumococcal Global Burden of Disease Study Team. Burden of disease caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae in children younger than 5 years: global estimates. Lancet. 2009;374:893–902. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Welte T, Torres A, Nathwani D. Clinical and economic burden of community-acquired pneumonia among adults in Europe. Thorax. 2012;67:71–9. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Blasi F, Mantero M, Santus P, Tarsia P. Understanding the burden of pneumococcal disease in adults. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012;18(Suppl 5):7–14. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Lozano R, Naghavi M, Foreman K, Lim S, Shibuya K, Aboyans V, et al. Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380:2095–128. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Romney MG, Hull MW, Gustafson R, Sandhu J, Champagne S, Wong T, et al. Large community outbreak of Streptococcus pneumoniae serotype 5 invasive infection in an impoverished, urban population. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47:768–74. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Infectious Diseases. Recommendations for the prevention of Streptococcus pneumoniae infections in infants and children: use of 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV13) and pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (PPSV23). Pediatrics. 2010;126:186–90. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- van der Poll T, Opal SM. Pathogenesis, treatment, and prevention of pneumococcal pneumonia. Lancet. 2009;374:1543–56. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Schillberg E, Isaac M, Deng X, Peirano G, Wylie JL, Van Caeseele P, et al. Outbreak of invasive Streptococcus pneumoniae serotype 12F among a marginalized inner-city population in Winnipeg, Canada, 2009-2011. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59:651–7. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Le Hello S, Watson M, Levy M, Marcon S, Brown M, Yvon JF, et al. Invasive serotype 1 Streptococcus pneumoniae outbreaks in the South Pacific from 2000 to 2007. J Clin Microbiol. 2010;48:2968–71. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Weinberger DM, Malley R, Lipsitch M. Serotype replacement in disease after pneumococcal vaccination. Lancet. 2011;378:1962–73.

- Feikin DR, Kagucia EW, Loo JD, Link-Gelles R, Puhan MA, Cherian T, et al.; Serotype Replacement Study Group. Serotype-specific changes in invasive pneumococcal disease after pneumococcal conjugate vaccine introduction: a pooled analysis of multiple surveillance sites. PLoS Med. 2013;10:e1001517. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Wyllie AL, Wijmenga-Monsuur AJ, van Houten MA, Bosch AA, Groot JA, van Engelsdorp Gastelaars J, et al. Molecular surveillance of nasopharyngeal carriage of Streptococcus pneumoniae in children vaccinated with conjugated polysaccharide pneumococcal vaccines. Sci Rep. 2016;6:23809. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Flasche S, Van Hoek AJ, Sheasby E, Waight P, Andrews N, Sheppard C, et al. Effect of pneumococcal conjugate vaccination on serotype-specific carriage and invasive disease in England: a cross-sectional study. PLoS Med. 2011;8:e1001017. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Ben-Shimol S, Givon-Lavi N, Greenberg D, Dagan R. Pneumococcal nasopharyngeal carriage in children <5 years of age visiting the pediatric emergency room in relation to PCV7 and PCV13 introduction in southern Israel. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2016;12:268–76. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Ben-Shimol S, Greenberg D, Givon-Lavi N, Schlesinger Y, Somekh E, Aviner S, et al. Early impact of sequential introduction of 7-valent and 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine on IPD in Israeli children <5 years: an active prospective nationwide surveillance. Vaccine. 2014;32:3452–9. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Regev-Yochay G, Paran Y, Bishara J, Oren I, Chowers M, Tziba Y, et al.; IAIPD group. Early impact of PCV7/PCV13 sequential introduction to the national pediatric immunization plan, on adult invasive pneumococcal disease: A nationwide surveillance study. Vaccine. 2015;33:1135–42. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Robinson DA, Turner JS, Facklam RR, Parkinson AJ, Breiman RF, Gratten M, et al. Molecular characterization of a globally distributed lineage of serotype 12F Streptococcus pneumoniae causing invasive disease. J Infect Dis. 1999;179:414–22. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Zulz T, Wenger JD, Rudolph K, Robinson DA, Rakov AV, Bruden D, et al. Molecular characterization of Streptococcus pneumoniae serotype 12F isolates associated with rural community outbreaks in Alaska. J Clin Microbiol. 2013;51:1402–7. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Rakov AV, Ubukata K, Robinson DA. Population structure of hyperinvasive serotype 12F, clonal complex 218 Streptococcus pneumoniae revealed by multilocus boxB sequence typing. Infect Genet Evol. 2011;11:1929–39. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Hoge CW, Reichler MR, Dominguez EA, Bremer JC, Mastro TD, Hendricks KA, et al. An epidemic of pneumococcal disease in an overcrowded, inadequately ventilated jail. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:643–8. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Deng X, Peirano G, Schillberg E, Mazzulli T, Gray-Owen SD, Wylie JL, et al. Whole-genome sequencing reveals the origin and rapid evolution of an emerging outbreak strain of Streptococcus pneumoniae 12F. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;62:1126–32. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Brueggemann AB, Muroki BM, Kulohoma BW, Karani A, Wanjiru E, Morpeth S, et al. Population genetic structure of Streptococcus pneumoniae in Kilifi, Kenya, prior to the introduction of pneumococcal conjugate vaccine. PLoS One. 2013;8:e81539. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Del Amo E, Esteva C, Hernandez-Bou S, Galles C, Navarro M, Sauca G, et al.; Catalan Study Group of Invasive Pneumococcal Disease. Serotypes and clonal diversity of Streptococcus pneumoniae causing invasive disease in the era of PCV13 in Catalonia, Spain. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0151125. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Israel Central Bureau of Statistics. Statistical abstract of Israel no. 63. 2012 [cited 2017 Dec 28]. http://www.cbs.gov.il/reader/shnaton/shnatone_new.htm?CYear=2012&Vol=63&CSubject=19

- Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing: eighteenth informational supplement (M100-S18). Wayne (PA): The Institute, 2008.

- Elberse KE, van de Pol I, Witteveen S, van der Heide HG, Schot CS, van Dijk A, et al. Population structure of invasive Streptococcus pneumoniae in The Netherlands in the pre-vaccination era assessed by MLVA and capsular sequence typing. PLoS One. 2011;6:e20390. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- McEllistrem MC, Stout JE, Harrison LH. Simplified protocol for pulsed-field gel electrophoresis analysis of Streptococcus pneumoniae. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:351–3.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Enright MC, Spratt BG. A multilocus sequence typing scheme for Streptococcus pneumoniae: identification of clones associated with serious invasive disease. Microbiology. 1998;144:3049–60. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Streptococcus pneumoniae MLST website [cited 2017 Dec 28]. http://pubmlst.org/spneumoniae/ /

- Varon E, Cohen R, Béchet S, Doit C, Levy C. Invasive disease potential of pneumococci before and after the 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine implementation in children. Vaccine. 2015;33:6178–85. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Chiba N, Morozumi M, Sunaoshi K, Takahashi S, Takano M, Komori T, et al.; IPD Surveillance Study Group. Serotype and antibiotic resistance of isolates from patients with invasive pneumococcal disease in Japan. Epidemiol Infect. 2010;138:61–8. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Song JY, Nahm MH, Moseley MA. Clinical implications of pneumococcal serotypes: invasive disease potential, clinical presentations, and antibiotic resistance. J Korean Med Sci. 2013;28:4–15. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Skoczyńska A, Sadowy E, Bojarska K, Strzelecki J, Kuch A, Gołębiewska A, et al.; Participants of laboratory-based surveillance of community acquired invasive bacterial infections (BINet). The current status of invasive pneumococcal disease in Poland. Vaccine. 2011;29:2199–205. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Hausdorff WP, Feikin DR, Klugman KP. Epidemiological differences among pneumococcal serotypes. Lancet Infect Dis. 2005;5:83–93. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Cherian T, Steinhoff MC, Harrison LH, Rohn D, McDougal LK, Dick J. A cluster of invasive pneumococcal disease in young children in child care. JAMA. 1994;271:695–7. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Lee EH, Hosea S, Schulman E, Bellomy A, Jackson D, Glass N, et al. Streptococcus pneumoniae serotype 12F outbreak in a homeless population—California, 2004. In: Conference program and abstracts: 54th Annual Epidemic Intelligence Services (EIS) Conference, April 11–15, 2005, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Georgia. Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2005. p. 79.

- Shouval DS, Greenberg D, Givon-Lavi N, Porat N, Dagan R. Site-specific disease potential of individual Streptococcus pneumoniae serotypes in pediatric invasive disease, acute otitis media and acute conjunctivitis. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2006;25:602–7. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Porat N, Benisty R, Trefler R, Givon-Lavi N, Dagan R. Clonal distribution of common pneumococcal serotypes not included in the 7-valent conjugate vaccine (PCV7): marked differences between two ethnic populations in southern Israel. J Clin Microbiol. 2012;50:3472–7. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

Figures

Tables

Cite This ArticleTable of Contents – Volume 24, Number 3—March 2018

| EID Search Options |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Please use the form below to submit correspondence to the authors or contact them at the following address:

Assaf Rokney, Government Central Laboratories, Ministry of Health, Eliav 9, Jerusalem 91342, Israel

Top