Volume 24, Number 8—August 2018

Dispatch

Detection of Dengue Virus among Children with Suspected Malaria, Accra, Ghana

Figure 2

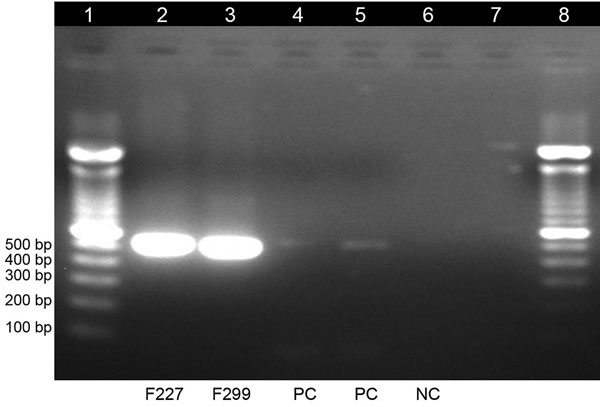

Figure 2. Gel electrophoresis of dengue virus–specific RT-PCR products in study of dengue virus among 166 children with suspected malaria, Accra, Ghana, October 2016–July 2017. We completed a conventional RT-PCR assay by using dengue-specific primers from Lanciotti et al. (15) to confirm the results of the TaqMan array card assays. The amplification products (expected size 511 bp) were electrophoresed on 2% agarose gel, stained with ethidium bromide, and viewed under ultraviolet light. Lane 1, molecular weight marker; lanes 2 and 3, test samples; lanes 4 and 5, positive controls; lane 6, negative control; lane 7, empty; lane 8, molecular weight marker. RT-PCR, reverse transcription PCR.

References

- Bisoffi Z, Buonfrate D. When fever is not malaria. Lancet Glob Health. 2013;1:e11–2. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Malm KL, Bart-Plange C, Armah G, Gyapong J, Adjei SO, Koram K, et al. Malaria as a cause of acute febrile illness in an urban pediatric population in Ghana. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2012;5(Suppl 1):401.

- Isiguzo C, Anyanti J, Ujuju C, Nwokolo E, De La Cruz A, Schatzkin E, et al. Presumptive treatment of malaria from formal and informal drug vendors in Nigeria. PLoS One. 2014;9:e110361. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Stoler J, Awandare GA. Febrile illness diagnostics and the malaria-industrial complex: a socio-environmental perspective. BMC Infect Dis. 2016;16:683. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Oyero OG, Ayukekbong JA. High dengue NS1 antigenemia in febrile patients in Ibadan, Nigeria. Virus Res. 2014;191:59–61. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Ridde V, Agier I, Bonnet E, Carabali M, Dabiré KR, Fournet F, et al. Presence of three dengue serotypes in Ouagadougou (Burkina Faso): research and public health implications. Infect Dis Poverty. 2016;5:23. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Tarnagda Z, Cissé A, Bicaba BW, Diagbouga S, Sagna T, Ilboudo AK, et al. Dengue Fever in Burkina Faso, 2016. Emerg Infect Dis. 2018;24:170–2. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Stoler J, Al Dashti R, Anto F, Fobil JN, Awandare GA. Deconstructing “malaria”: West Africa as the next front for dengue fever surveillance and control. Acta Trop. 2014;134:58–65. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Liu J, Ochieng C, Wiersma S, Ströher U, Towner JS, Whitmer S, et al. Development of a TaqMan array card for acute-febrile-illness outbreak investigation and surveillance of emerging pathogens, including Ebola virus. J Clin Microbiol. 2016;54:49–58. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Hogan B, Eibach D, Krumkamp R, Sarpong N, Dekker D, Kreuels B, et al. Malaria coinfections in febrile pediatric inpatients : a hospital-based study from Ghana. 2018;(March):3–10.

- Huhtamo E, Uzcátegui NY, Siikamäki H, Saarinen A, Piiparinen H, Vaheri A, et al. Molecular epidemiology of dengue virus strains from Finnish travelers. Emerg Infect Dis. 2008;14:80–3. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Stoler J, Delimini RK, Bonney JHK, Oduro AR, Owusu-Agyei S, Fobil JN, et al. Evidence of recent dengue exposure among malaria parasite-positive children in three urban centers in Ghana. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2015;92:497–500. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Fact sheet for healthcare providers: interpreting Trioplex Real-time RT-PCR Assay (Trioplex rRT-PCR) results. 2017;(March). https://www.cdc.gov/zika/pdfs/Fact-sheet-for-HCP-EUA-Trioplex-RT-PCR-Zika.pdf

- Johnson BW, Russell BJ, Lanciotti RS. Serotype-specific detection of dengue viruses in a fourplex real-time reverse transcriptase PCR assay. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43:4977–83. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Lanciotti RS, Calisher CH, Gubler DJ, Chang GJ, Vorndam AV. Rapid detection and typing of dengue viruses from clinical samples by using reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30:545–51.PubMedGoogle Scholar

Page created: July 18, 2018

Page updated: July 18, 2018

Page reviewed: July 18, 2018

The conclusions, findings, and opinions expressed by authors contributing to this journal do not necessarily reflect the official position of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, the Public Health Service, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, or the authors' affiliated institutions. Use of trade names is for identification only and does not imply endorsement by any of the groups named above.