Volume 26, Number 4—April 2020

Research

Comprehensive Profiling of Zika Virus Risk with Natural and Artificial Mitigating Strategies, United States

Figure 2

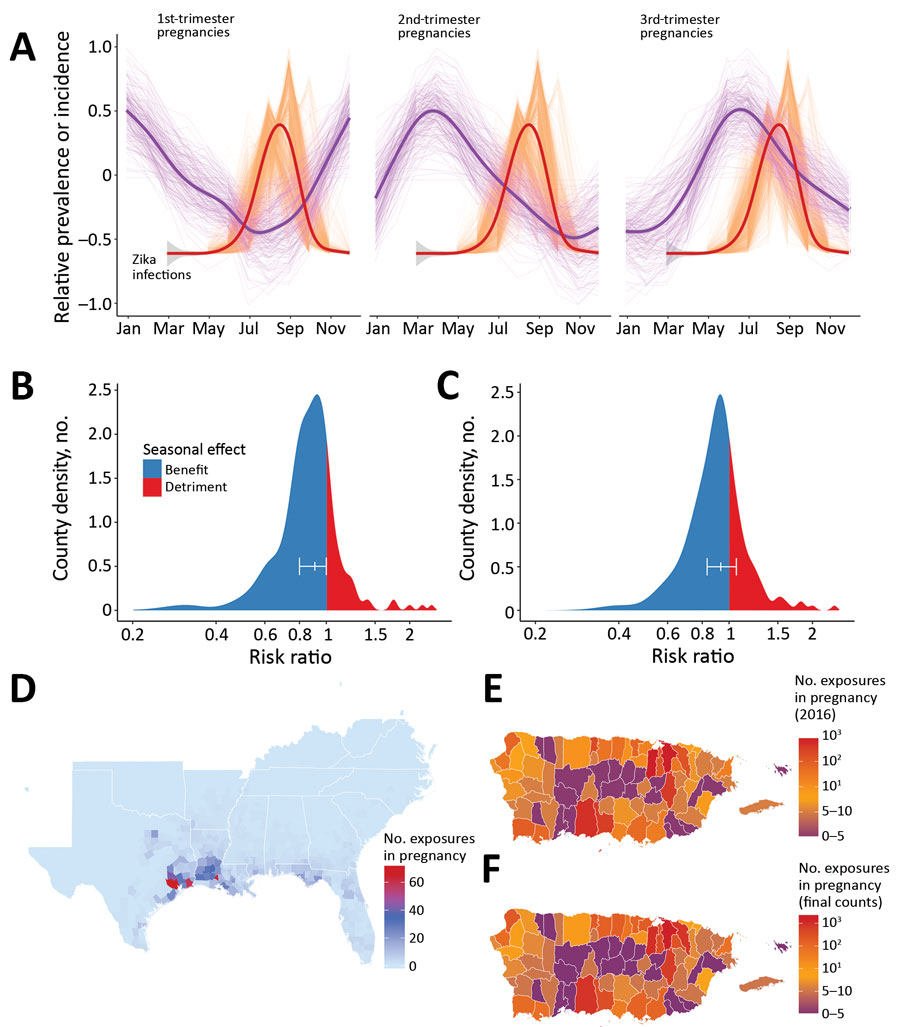

Figure 2. Zika virus infections during pregnancy and effects of natural birth dynamics, United States including Puerto Rico. A) Standardized prevalence of first-, second-, and third-trimester pregnancies throughout a year in the southeastern United States and Texas are plotted against the simulated and standardized Zika epidemic curves for each county and for every month of import. Thin purple lines indicate county-specific prevalence of pregnancy in each respective trimester, and thick purple lines show a generalized additive model fit. Thin orange lines indicate median outbreak per county, including distinct lines for each month of import during March–November. Thick orange line is a generalized additive model fit to the county-level data. B, C) Zika virus exposure risk ratio and 95% CI during (B) first (versus third) and (C) second (versus third) trimester of pregnancy, driven by the dynamics depicted in panel A (Appendix Table 2). D) Median number of infections (simulated) during pregnancy when index cases are imported during peak vector abundance. E, F) Median number of infections (simulated) during pregnancy for each municipality (E) in Puerto Rico in 2016 and (F) over the entire epidemic. Data in panels E and F include index cases that were introduced into each municipality to correspond with initial introductions reported in the current epidemic

1These authors contributed equally to this article.