Volume 26, Number 5—May 2020

Research

Effectiveness of Live Poultry Market Interventions on Human Infection with Avian Influenza A(H7N9) Virus, China

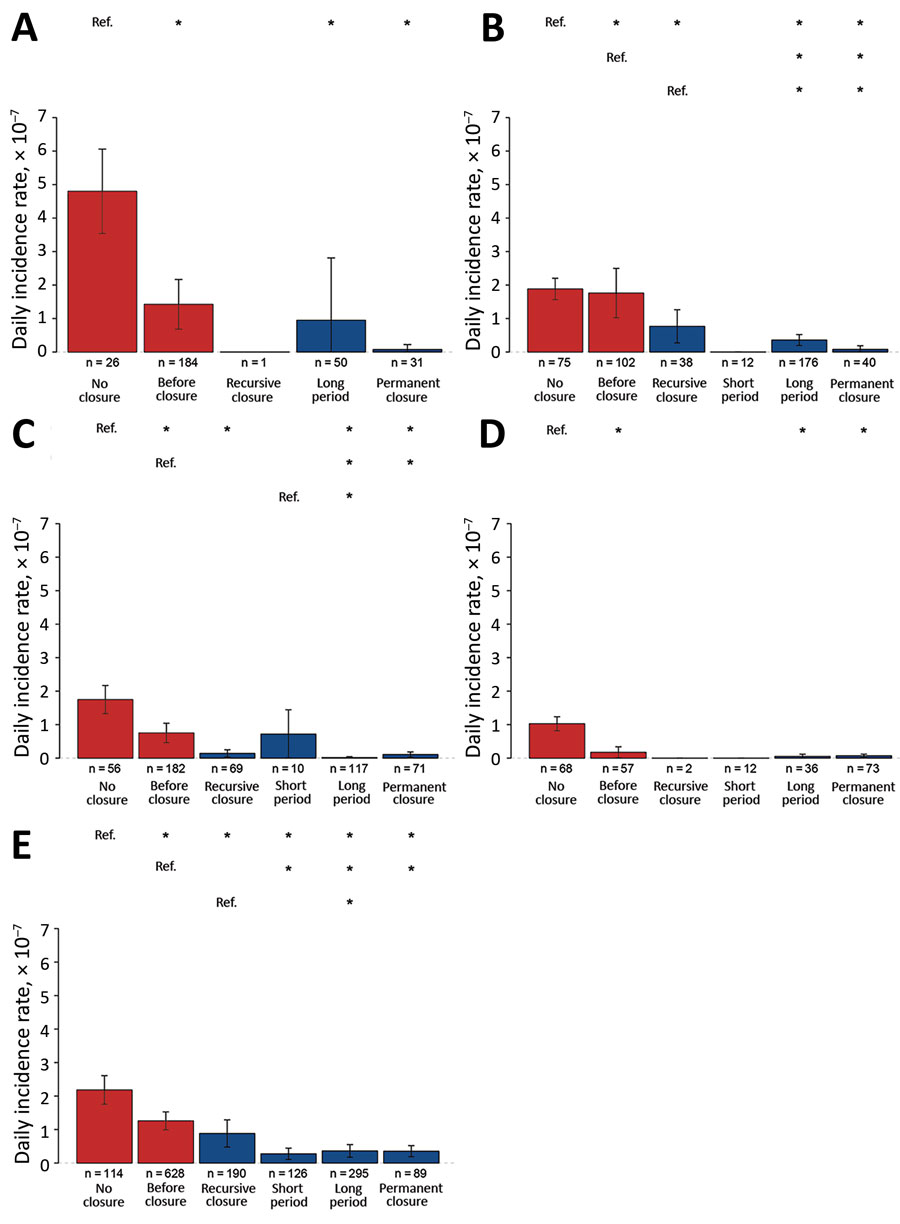

Figure 2

Figure 2. Estimated daily incidence rates in counties with various levels of live poultry market closures across waves of influenza A(H7N9) infections, by duration of closure, China, 2013–2017. A) Wave 1; B) wave 2; C) wave 3; D) wave 4; E) wave 5. Error bars indicate 95% CIs. Asterisks (*) above bars indicate statistically significant (p<0.05) differences between daily incidence rates and reference category (Ref.) rates. Duration categories: no closure during epidemic wave; permanent closure, permanently closed within the epidemic wave or for the entire epidemic wave duration; long-period closure (>14 days within the epidemic wave [10,17]); short-period closure (<14 days within the epidemic wave); and recursive closure, whereby LPMs were closed for 1 or 2 day with a repetition of the closing over time (the closing might be implemented weekly, biweekly, or monthly).

References

- Liu D, Shi W, Shi Y, Wang D, Xiao H, Li W, et al. Origin and diversity of novel avian influenza A H7N9 viruses causing human infection: phylogenetic, structural, and coalescent analyses. Lancet. 2013;381:1926–32. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- World Health Organization. Human infection with avian influenza A(H7N9) virus—China. 2019 [cited 2019 Nov 23]. https://www.who.int/csr/don/13-september-2017-ah7n9-china

- Zhou L, Chen E, Bao C, Xiang N, Wu J, Wu S, et al. Clusters of human infection and human-to-human transmission of avian influenza A(H7N9) virus, 2013–2017. Emerg Infect Dis. 2018;24:397–400. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Bertran K, Balzli C, Kwon YK, Tumpey TM, Clark A, Swayne DE. Airborne transmission of highly pathogenic influenza virus during processing of infected poultry. Emerg Infect Dis. 2017;23:1806–14. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Mutations on H7N9 virus have been identified in H7N9 patients in China. 2017 [cited 2018 Apr 20]. http://www.chinacdc.cn/jkzt/crb/zl/rgrgzbxqlgg/rgrqlgyp/201702/t20170219_138185.html

- Qi W, Jia W, Liu D, Li J, Bi Y, Xie S, et al. Emergence and adaptation of a novel highly pathogenic H7N9 influenza virus in birds and humans from a 2013 human-infecting low-pathogenic ancestor. J Virol. 2018;92:

e00921-17 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Artois J, Jiang H, Wang X, Qin Y, Pearcy M, Lai S, et al. Changing geographic patterns and risk factors for avian influenza A(H7N9) infections in humans, China. Emerg Infect Dis. 2018;24:87–94. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Lam TT, Wang J, Shen Y, Zhou B, Duan L, Cheung CL, et al. The genesis and source of the H7N9 influenza viruses causing human infections in China. Nature. 2013;502:241–4. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Wang X, Jiang H, Wu P, Uyeki TM, Feng L, Lai S, et al. Epidemiology of avian influenza A H7N9 virus in human beings across five epidemics in mainland China, 2013-17: an epidemiological study of laboratory-confirmed case series. Lancet Infect Dis. 2017;17:822–32. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- He Y, Liu P, Tang S, Chen Y, Pei E, Zhao B, et al. Live poultry market closure and control of avian influenza A(H7N9), Shanghai, China. Emerg Infect Dis. 2014;20:1565–6. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Friedrich MJ. Closing live poultry markets slowed avian flu in China. JAMA. 2013;310:2497. DOIGoogle Scholar

- Liu H, Chen Z, Xiao X, Lu J, Di B, Li K, et al. [Effects of resting days on live poultry markets in controlling the avian influenza pollution]. Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi. 2014;35:832–6.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Kang M, He J, Song T, Rutherford S, Wu J, Lin J, et al. Environmental sampling for avian influenza A(H7N9) in live-poultry markets in Guangdong, China. PLoS One. 2015;10:

e0126335 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Yuan J, Lau EH, Li K, Leung YH, Yang Z, Xie C, et al. Effect of live poultry market closure on avian influenza A(H7N9) virus activity in Guangzhou, China, 2014. Emerg Infect Dis. 2015;21:1784–93. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Cheng W, Wang X, Shen Y, Yu Z, Liu S, Cai J, et al. Comparison of the three waves of avian influenza A(H7N9) virus circulation since live poultry markets were permanently closed in the main urban areas in Zhejiang Province, July 2014-June 2017. Influenza Other Respir Viruses. 2018;12:259–66. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Yu H, Cowling BJ, Liao Q, Fang VF, Zhou S, Wu P, et al. Effect of closure of live poultry markets on poultry-to-person transmission of avian influenza A H7N9 virus: an ecological study. Lancet 2014;383:541–8. DOIGoogle Scholar

- Kucharski AJ, Mills HL, Donnelly CA, Riley S. Transmission potential of influenza A(H7N9) virus, China, 2013–2014. Emerg Infect Dis. 2015;21:852–5. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Virlogeux V, Feng L, Tsang TK, Jiang H, Fang VJ, Qin Y, et al. Evaluation of animal-to-human and human-to-human transmission of influenza A (H7N9) virus in China, 2013-15. Sci Rep. 2018;8:552. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Li J, Rao Y, Sun Q, Wu X, Jin J, Bi Y, et al. Identification of climate factors related to human infection with avian influenza A H7N9 and H5N1 viruses in China. Sci Rep. 2015;5:18094. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Shaman J, Kohn M. Absolute humidity modulates influenza survival, transmission, and seasonality. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:3243–8. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Yuan J, Tang X, Yang Z, Wang M, Zheng B. Enhanced disinfection and regular closure of wet markets reduced the risk of avian influenza A virus transmission. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;58:1037–8. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Soares Magalhães RJ, Zhou X, Jia B, Guo F, Pfeiffer DU, Martin V. Live poultry trade in Southern China provinces and HPAIV H5N1 infection in humans and poultry: the role of Chinese New Year festivities. PLoS One. 2012;7:

e49712 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Hu J, Zhu Y, Zhao B, Li J, Liu L, Gu K, et al. Limited human-to-human transmission of avian influenza A(H7N9) virus, Shanghai, China, March to April 2013. Euro Surveill. 2014;19:20838. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Liao Q, Yuan J, Lau EH, Chen GY, Yang ZC, Ma XW, et al. Live bird exposure among the general public, Guangzhou, China, May 2013. PLoS One. 2015;10:

e0143582 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Nicita A. Avian influenza and the poultry trade. 2008 [cited 2020 Feb 20]. https://elibrary.worldbank.org/doi/abs/10.1596/1813-9450-4551

- Lau EH, Leung YH, Zhang LJ, Cowling BJ, Mak SP, Guan Y, et al. Effect of interventions on influenza A (H9N2) isolation in Hong Kong’s live poultry markets, 1999-2005. Emerg Infect Dis. 2007;13:1340–7. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Wu P, Wang L, Cowling BJ, Yu J, Fang VJ, Li F, et al. Live poultry exposure and public response to influenza A(H7N9) in urban and rural China during two epidemic waves in 2013–2014. PLoS One. 2015;10:

e0137831 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Offeddu V, Cowling BJ, Malik Peiris JS. Interventions in live poultry markets for the control of avian influenza: a systematic review. One Health. 2016;2:55–64. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Sims LD. Intervention strategies to reduce the risk of zoonotic infection with avian influenza viruses: scientific basis, challenges and knowledge gaps. Influenza Other Respir Viruses. 2013;7(Suppl 2):15–25. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Shi J, Deng G, Ma S, Zeng X, Yin X, Li M, et al. Rapid evolution of H7N9 highly pathogenic viruses that emerged in China in 2017. Cell Host Microbe. 2018;24:558–68.e7.

- Chen E, Wang MH, He F, Sun R, Cheng W, Zee BCY, et al. An increasing trend of rural infections of human influenza A (H7N9) from 2013 to 2017: A retrospective analysis of patient exposure histories in Zhejiang province, China. PLoS One. 2018;13:

e0193052 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

1These authors contributed equally to this article.

2These authors are joint senior authors.