Volume 26, Number 7—July 2020

Dispatch

Aerosol and Surface Distribution of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 in Hospital Wards, Wuhan, China, 2020

Abstract

To determine distribution of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 in hospital wards in Wuhan, China, we tested air and surface samples. Contamination was greater in intensive care units than general wards. Virus was widely distributed on floors, computer mice, trash cans, and sickbed handrails and was detected in air ≈4 m from patients.

As of March 30, 2020, approximately 750,000 cases of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) had been reported globally since December 2019 (1), severely burdening the healthcare system (2). The extremely fast transmission capability of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) has aroused concern about its various transmission routes.

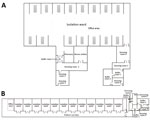

The main transmission routes for SARS-CoV-2 are respiratory droplets and close contact (3). Knowing the extent of environmental contamination of SARS-CoV-2 in COVID-19 wards is critical for improving safety practices for medical staff and answering questions about SARS-CoV-2 transmission among the public. However, whether SARS-CoV-2 can be transmitted by aerosols remains controversial, and the exposure risk for close contacts has not been systematically evaluated. Researchers have detected SARS-CoV-2 on surfaces of objects in a symptomatic patient’s room and toilet area (4). However, that study was performed in a small sample from regions with few confirmed cases, which might not reflect real conditions in outbreak regions where hospitals are operating at full capacity. In this study, we tested surface and air samples from an intensive care unit (ICU) and a general COVID-19 ward (GW) at Huoshenshan Hospital in Wuhan, China (Figure 1).

From February 19 through March 2, 2020, we collected swab samples from potentially contaminated objects in the ICU and GW as described previously (5). The ICU housed 15 patients with severe disease and the GW housed 24 patients with milder disease. We also sampled indoor air and the air outlets to detect aerosol exposure. Air samples were collected by using a SASS 2300 Wetted Wall Cyclone Sampler (Research International, Inc., https://www.resrchintl.com) at 300 L/min for of 30 min. We used sterile premoistened swabs to sample the floors, computer mice, trash cans, sickbed handrails, patient masks, personal protective equipment, and air outlets. We tested air and surface samples for the open reading frame (ORF) 1ab and nucleoprotein (N) genes of SARS-CoV-2 by quantitative real-time PCR. (Appendix).

Almost all positive results were concentrated in the contaminated areas (ICU 54/57, 94.7%; GW 9/9, 100%); the rate of positivity was much higher for the ICU (54/124, 43.5%) than for the GW (9/114, 7.9%) (Tables 1, 2). The rate of positivity was relatively high for floor swab samples (ICU 7/10, 70%; GW 2/13, 15.4%), perhaps because of gravity and air flow causing most virus droplets to float to the ground. In addition, as medical staff walk around the ward, the virus can be tracked all over the floor, as indicated by the 100% rate of positivity from the floor in the pharmacy, where there were no patients. Furthermore, half of the samples from the soles of the ICU medical staff shoes tested positive. Therefore, the soles of medical staff shoes might function as carriers. The 3 weak positive results from the floor of dressing room 4 might also arise from these carriers. We highly recommend that persons disinfect shoe soles before walking out of wards containing COVID-19 patients.

The rate of positivity was also relatively high for the surface of the objects that were frequently touched by medical staff or patients (Tables 1, 2). The highest rates were for computer mice (ICU 6/8, 75%; GW 1/5, 20%), followed by trash cans (ICU 3/5, 60%; GW 0/8), sickbed handrails (ICU 6/14, 42.9%; GW 0/12), and doorknobs (GW 1/12, 8.3%). Sporadic positive results were obtained from sleeve cuffs and gloves of medical staff. These results suggest that medical staff should perform hand hygiene practices immediately after patient contact.

Because patient masks contained exhaled droplets and oral secretions, the rate of positivity for those masks was also high (Tables 1, 2). We recommend adequately disinfecting masks before discarding them.

We further assessed the risk for aerosol transmission of SARS-CoV-2. First, we collected air in the isolation ward of the ICU (12 air supplies and 16 air discharges per hour) and GW (8 air supplies and 12 air discharges per hour) and obtained positive test results for 35% (14 samples positive/40 samples tested) of ICU samples and 12.5% (2/16) of GW samples. Air outlet swab samples also yielded positive test results, with positive rates of 66.7% (8/12) for ICUs and 8.3% (1/12) for GWs. These results confirm that SARS-CoV-2 aerosol exposure poses risks.

Furthermore, we found that rates of positivity differed by air sampling site, which reflects the distribution of virus-laden aerosols in the wards (Figure 2, panel A). Sampling sites were located near the air outlets (site 1), in patients’ rooms (site 2), and (site 3). SARS-CoV-2 aerosol was detected at all 3 sampling sites; rates of positivity were 35.7% (5/14) near air outlets, 44.4% (8/18) in patients’ rooms, and 12.5% (1/8) in the doctors’ office area. These findings indicate that virus-laden aerosols were mainly concentrated near and downstream from the patients. However, exposure risk was also present in the upstream area; on the basis of the positive detection result from site 3, the maximum transmission distance of SARS-CoV-2 aerosol might be 4 m. According to the aerosol monitoring results, we divided ICU workplaces into high-risk and low-risk areas (Figure 2, panel B). The high-risk area was the patient care and treatment area, where rate of positivity was 40.6% (13/32). The low-risk area was the doctors’ office area, where rate of positivity was 12.5% (1/8).

In the GW, site 1 was located near the patients (Figure 2, panel C). Site 2 was located ≈2.5 m upstream of the air flow relative to the heads of patients. We also sampled the indoor air of the patient corridor. Only air samples from site 1 tested positive (18.2%, 2/11). The workplaces in the GW were also divided into 2 areas: a high-risk area inside the patient wards (rate of positivity 12.5, 2/16) and a low-risk area outside the wards (rate of positivity 0) (Figure 2, panel D).

This study led to 3 conclusions. First, SARS-CoV-2 was widely distributed in the air and on object surfaces in both the ICU and GW, implying a potentially high infection risk for medical staff and other close contacts. Second, the environmental contamination was greater in the ICU than in the GW; thus, stricter protective measures should be taken by medical staff working in the ICU. Third, the SARS-CoV-2 aerosol distribution characteristics in the ICU indicate that the transmission distance of SARS-CoV-2 might be 4 m.

As of March 30, no staff members at Huoshenshan Hospital had been infected with SARS-CoV-2, indicating that appropriate precautions could effectively prevent infection. In addition, our findings suggest that home isolation of persons with suspected COVID-19 might not be a good control strategy. Family members usually do not have personal protective equipment and lack professional training, which easily leads to familial cluster infections (6). During the outbreak, the government of China strove to the fullest extent possible to isolate all patients with suspected COVID-19 by actions such as constructing mobile cabin hospitals in Wuhan (7), which ensured that all patients with suspected disease were cared for by professional medical staff and that virus transmission was effectively cut off. As of the end of March, the SARS-COV-2 epidemic in China had been well controlled.

Our study has 2 limitations. First, the results of the nucleic acid test do not indicate the amount of viable virus. Second, for the unknown minimal infectious dose, the aerosol transmission distance cannot be strictly determined.

Overall, we found that the air and object surfaces in COVID-19 wards were widely contaminated by SARS-CoV-2. These findings can be used to improve safety practices.

Drs. Guo, Z.Y. Wang, and S.F. Zhang are researchers at the Academy of Military Medical Sciences, Academy of Military Sciences in Beijing, China. Their research interests are the detection, monitoring, and risk assessment of aerosolized pathogens.

Acknowledgment

This work was financially supported by the National Major Research & Development Program of China (2020YFC0840800).

References

- World Health Organization. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) situation report-71 [cited 2020 Mar 30]. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/situation-reports

- Remuzzi A, Remuzzi G. COVID-19 and Italy: what next? Lancet. 2020;•••:

S0140-6736(20)30627-9 ; Epub ahead of print. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Peng X, Xu X, Li Y, Cheng L, Zhou X, Ren B. Transmission routes of 2019-nCoV and controls in dental practice. Int J Oral Sci. 2020;12:9. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Ong SWX, Tan YK, Chia PY, Lee TH, Ng OT, Wong MSY, et al. Air, surface environmental, and personal protective equipment contamination by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) from a symptomatic patient. JAMA. 2020; Epub ahead of print. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Zhang Y, Gong Y, Wang C, Liu W, Wang Z, Xia Z, et al. Rapid deployment of a mobile biosafety level-3 laboratory in Sierra Leone during the 2014 Ebola virus epidemic. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2017;11:

e0005622 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Huang R, Xia J, Chen Y, Shan C, Wu C. A family cluster of SARS-CoV-2 infection involving 11 patients in Nanjing, China. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;•••:

S1473-3099(20)30147-X ; Epub ahead of print. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Novel Coronavirus Pneumonia Emergency Response Key Places Protection and Disinfection Technology Team, Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. [Health protection guideline of mobile cabin hospitals during Novel Coronavirus Pneumonia (NPC) outbreak] [in Chinese]. Zhonghua Yu Fang Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2020;54:

E006 .PubMedGoogle Scholar

Figures

Tables

Cite This ArticleOriginal Publication Date: April 10, 2020

1These authors contributed equally to this article.

Table of Contents – Volume 26, Number 7—July 2020

| EID Search Options |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Please use the form below to submit correspondence to the authors or contact them at the following address:

Wei Chen, Bing Lu, and Yu-Wei Gao, Academy of Military Medical Sciences, Academy of Military Sciences, 27 Taiping Rd, Haidian District, Beijing, China; , , and

Top