Volume 27, Number 10—October 2021

Dispatch

Genomic Sequencing of SARS-CoV-2 E484K Variant B.1.243.1, Arizona, USA

Cite This Article

Citation for Media

Abstract

Genomic surveillance can provide early insights into new circulating severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) variants. While conducting genomic surveillance (1,663 cases) from December 2020–April 2021 in Arizona, USA, we detected an emergent E484K-harboring variant, B.1.243.1. This finding demonstrates the importance of real-time SARS-CoV-2 surveillance to better inform public health responses.

Genomic sequencing surveillance tracks the evolution of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) and can provide early-warning insight of new variants circulating in communities. SARS-CoV-2 continues to acquire mutations in its genome as it spreads around the world. Although many mutations have little or no consequence on virus fitness, some mutations affect receptor binding or reduce antibody neutralization (1,2). Other mutations have been associated with increased transmission and clinical disease severity (3; Y. Liu et al., unpub. data, https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.03.08.434499). As of July 2021, the US SARS-CoV-2 Interagency Group has designated 4 variants of concern (VOC) and 7 variants of interest (VOI) in the United States based on the combination of mutations and associated attributes (5). Several of these VOCs and VOIs (e.g., Beta/B.1.351, Gamma/P.1, Delta/B.1.617.2) harbor the E484K mutation in the spike glycoprotein gene (4). Studies have demonstrated that the E484K mutation reduces antibody neutralization (2,5,6). E484K variants have also been identified in reinfection cases, suggesting a role in breakthrough infections (2,5–7); these findings indicate the need to monitor for SARS-CoV-2 variants in real time.

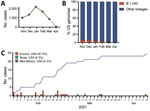

In an effort to provide statewide genomic surveillance, we sequenced the SARS-CoV-2 genome from 1,663 positive samples collected December 28, 2020–April 12, 2021 in Arizona, United States. Samples were primarily from Maricopa (56.9%), Coconino (26.4%), and Pima (8.5%) Counties. Study participants were 53.8% male, 46.2% female; age range was 5–81 years (median of 25 years). We successfully sequenced 1,538 (92.5%) high-quality complete genomes and found VOCs Alpha/B.1.1.7 (n = 336, 21.8%), Gamma/P.1 (n = 5, 0.33%), Beta/B.1.351 (n = 1, 0.07%), and Delta/B.1.617.2 (n = 1, 0.07%) and VOIs Epsilon/B.1.427/B.1.429 (n = 416, 27.0%), Iota/B.1.526 (n = 7, 0.5%), and Zeta/P.2 (n = 8, 0.5%) (Appendix Table 1). We detected 8 genomes associated with a common B.1.243 variant that had acquired an E484K mutation in the spike protein. The novel variant had 11 lineage-defining mutations, including V213G and E484K in the spike gene, a 9-nt deletion in open reading frame (ORF) 1ab (ΔSGF3675–77), a 3-nt insertion in the noncoding intergenic region upstream of the N gene, and other synonymous substitutions (Appendix Table 2, Figure 1). These 11 conserved mutations are distinct from the mutations associated with the parent lineage, B.1.243. The parent B.1.243 lineage is a common variant circulating in the United States that was observed in March 2020, early in the pandemic (Figure, panels A–C). The B.1.243 parent lineage encodes the spike gene D614G substitution but none of the other concerning mutations (Appendix Table 3, Figure 1). This new E484K-harboring variant has been officially designated as B.1.243.1 using the pangolin nomenclature system (8).

We examined the GISAID repository (https://www.gisaid.org) for additional B.1.243.1 genomes to determine its prevalence and geographic distribution. We found that B.1.243.1 is predominantly established in Arizona. Of 24 cases of B.1.243.1 sequenced during February 1–April 14, a total of 21 cases were from Arizona (Figure, panel C; Appendix Table 4). Two cases were sequenced from samples collected in Texas on February 24 and March 20 and another from a sample collected in New Mexico on March 8, suggesting that B.1.243.1 had spread to other states. We also identified 2 instances in which the parent B.1.243 lineage independently acquired the E484K mutation. However, both genomes lacked the other B.1.243.1 lineage-defining mutations and appear to be dead-end transmission events. Phylogenetic analyses indicate that the B.1.243.1 sequences form a monophyletic clade within the B.1.243 clade (Appendix Figure 2). Multiple internal branching observed in the B.1.243.1 clade indicates continued diversification of the lineage sequences, which suggests that B.1.243.1 was being established in circulation within Arizona. In contrast, the 2 additional B.1.243 cases bearing the E484K mutation alone were phylogenetically distinct from the B.1.243.1 clade, suggesting that those isolates had evolved independently.

Genomic sequencing surveillance can provide early warnings of emergent variants. Because phylogenetic evidence suggested that B.1.243.1 was beginning to circulate in Arizona, the Arizona Department of Health Services (ADHS) was notified on March 18, 2021, and contact tracing was performed for the early B.1.243.1 cases. Of the case-patients who were interviewed, none reported connection to other patients. At the time of reporting (May 2021), the most recent case of B.1.243.1 had been reported on April 14, 2021 (Appendix Table 4). The limited spread of B.1.243.1 coincides with competition from the rapid rise in transmission of the Alpha (B.1.1.7) variant in the United States (9).

A limitation of this study is that the sequencing surveillance represented 0.31% of 503,825 total SARS-CoV-2 cases in Arizona during the study period. Targeted sampling efforts, such as prescreening samples for the E484K mutation by PCR-based assays, would complement random sampling for genomic sequencing surveillance. Our study highlights the need for sustained genomic surveillance in public health strategies and responses.

Mr. Skidmore is a bioinformatician at Arizona State University under the supervision of Efrem Lim. His primary research interests include the role of the microbiome in health and disease and tracking the spread of infectious diseases.

Acknowledgments

We thank the authors from originating laboratories responsible for obtaining the specimens and the submitting laboratories where genetic sequence data were generated and shared via the GISAID initiative, on which part of the research is based. We thank Brenna Garrett, Kenneth Komatsu and the Arizona Department of Health Services, and local health departments for contact tracing.

This research was supported in part by the Arizona State University Knowledge Enterprise and Arizona Department of Health Services. E.S.L. is supported in part by NIH grant R00DK107923.

Author contributions: methodology, P.T.S., E.A.K., L.A.H., R.M., L.I.W., N.J.M., J.M.B., V.H., E.S.L.; investigation, P.T.S., E.A.K., R.M., E.S.L.; resources, L.I.W., V.H., J.L., V.M.; data curation, P.T.S., E.A.K., R.M.; original draft of manuscript, P.T.S., E.A.K., R.M., E.S.L.; review and editing of manuscript, P.T.S., E.A.K., L.A.H., R.M., E.S.L.; supervision, J.L., V.M., E.S.L.; conceptualization, E.S.L.; funding acquisition, E.S.L. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

References

- Starr TN, Greaney AJ, Hilton SK, Ellis D, Crawford KHD, Dingens AS, et al. Deep mutational scanning of SARS-CoV-2 receptor binding domain reveals constraints on folding and ACE2 binding. Cell. 2020;182:1295–1310.e20. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Garcia-Beltran WF, Lam EC, St Denis K, Nitido AD, Garcia ZH, Hauser BM, et al. Multiple SARS-CoV-2 variants escape neutralization by vaccine-induced humoral immunity. Cell. 2021;184:2372–2383.e9. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Challen R, Brooks-Pollock E, Read JM, Dyson L, Tsaneva-Atanasova K, Danon L. Risk of mortality in patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 variant of concern 202012/1: matched cohort study. BMJ. 2021;372:n579. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. SARS-CoV-2 variant classifications and definitions. 2021 [cited 2021 Mar 22]. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/cases-updates/variant-surveillance/variant-info.html

- Liu Z, VanBlargan LA, Bloyet L-M, Rothlauf PW, Chen RE, Stumpf S, et al. Identification of SARS-CoV-2 spike mutations that attenuate monoclonal and serum antibody neutralization. Cell Host Microbe. 2021;29:477–488.e4. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Chen RE, Zhang X, Case JB, Winkler ES, Liu Y, VanBlargan LA, et al. Resistance of SARS-CoV-2 variants to neutralization by monoclonal and serum-derived polyclonal antibodies. Nat Med. 2021;27:717–26. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Nonaka CKV, Franco MM, Gräf T, de Lorenzo Barcia CA, de Ávila Mendonça RN, de Sousa KAF, et al. Genomic evidence of SARS-CoV-2 reinfection involving E484K spike mutation, Brazil. Emerg Infect Dis. 2021;27:1522–4. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Rambaut A, Holmes EC, O’Toole Á, Hill V, McCrone JT, Ruis C, et al. A dynamic nomenclature proposal for SARS-CoV-2 lineages to assist genomic epidemiology. Nat Microbiol. 2020;5:1403–7. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Variant proportions. 2021 May 18 [cited 2021 May 19]. https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/?CDC_AA_refVal=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.cdc.gov%2Fcoronavirus%2F2019-ncov%2Fcases-updates%2Fvariant-proportions.html#variant-proportions

Figure

Cite This ArticleOriginal Publication Date: August 23, 2021

Table of Contents – Volume 27, Number 10—October 2021

| EID Search Options |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Please use the form below to submit correspondence to the authors or contact them at the following address:

Efrem S. Lim, Arizona State University, PO Box 876101, Tempe, AZ 85287, USA

Top