Volume 27, Number 6—June 2021

Dispatch

Recurrent Swelling and Microfilaremia Caused by Dirofilaria repens Infection after Travel to India

Cite This Article

Citation for Media

Abstract

Human subcutaneous dirofilariasis is an emerging mosquitoborne zoonosis. A traveler returning to Germany from India experienced Dirofilaria infection with concomitant microfilaremia. Molecular analysis indicated Dirofilaria repens nematodes of an Asian genotype. Microfilaremia showed no clear periodicity. Presence of Wolbachia endosymbionts enabled successful treatment with doxycycline.

Dirofilariasis is a zoonotic filarial infection transmitted through the bite of mosquitoes of various species. Several species of Dirofilaria microfilariae, most frequently D. repens and D. immitis, can infect humans. D. repens nematodes cause microfilaremic infection in dogs and other carnivores, which serve as reservoirs. Because humans are aberrant hosts, larvae usually develop into immature, nonfertile worms unable to produce microfilariae (1). Patients often report recurrent swelling with subsequent development of subcutaneous nodules, most commonly in the periorbital region (2). For most cases, surgical removal and histopathologic examination of the worm leads to diagnosis (3). D. repens microfilariae circulating in peripheral blood have been detected in humans only rarely (4,5), and information on periodicity of microfilaremia in aberrant hosts is lacking. One case report describes sampling of D. repens microfilariae from morning to midday on a single day and detection of microfilariae in the morning (5). Sequencing of the parasite’s mitochondrial 12S rDNA has revealed European, African, and Asian genotypes of D. repens microfilariae. Successful treatment of D. repens infection with doxycycline, which targets the bacterial endosymbiont Wolbachia, has been reported (6). To our knowledge, Wolbachia bacteria have not been detected in D. repens microfilariae of the Asian genotype.

In April 2020, a 38-year-old man visited the outpatient clinic for tropical medicine at the Bernhard Nocht Institute for Tropical Medicine (Hamburg, Germany) 1 week after undergoing endonasal surgery for chronic sinusitis, reporting recurrent facial swelling. Nasal congestion and putrid discharge had started during a 5-week stay in Mysore, South India, his eighth trip in 5 years to the region to attend yoga classes. Two months after returning to Germany, he underwent therapeutic endoscopic septoplasty. Postoperatively, a soft tissue swelling in the right infraorbital and temporal region and general apathy developed, unresponsive to antibacterial therapy. Over 5 weeks, a low-grade eosinophilia of 0.72 × 109/L (10% of total leukocytes) increased to 0.94 × 109/L (14%). The result of an in-house panfilarial IgG-detecting ELISA that used a D. immitis extract as antigen was positive. Liver and kidney function test and serologic test results for Strongyloides, Toxocara, Fasciola, Paragonimus, Cysticerca, and Gnathostoma were unremarkable.

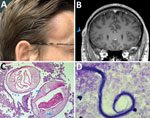

Five weeks after his initial visit to our clinic, the patient noticed a painless temporal mass (Figure 1, panel A). Magnetic resonance imaging demonstrated a 10-mm encapsulated lenticular formation in the deep subcutaneous tissue (Figure 1, panel B). The lesion was surgically removed, and histologic examination showed an adult nematode (Figure 1, panel C). Filtration of 5 mL peripheral blood after hypotonic lysis of blood cells and subsequent Giemsa staining of the filter revealed microfilariae with the morphologic characteristics of D. repens (7) (Figure 1, panel D; Appendix; Video 1; Video 2). Sequencing and BLAST analysis (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi) of a 463-bp fragment of the mitochondrial 12S rDNA (8) amplified from the adult worm and the microfilariae revealed 97.9%–99.2% homology with the Asian genotype of D. repens isolates from India (GenBank accession nos. GQ292761, KX265050, MT808309), followed by 95.6% homology with D. repens isolates from Europe (Greece, accession no. MK192091; Italy accession no., KX265072; Hungary, accession no. KX265070).

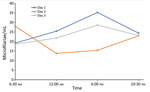

To assess possible periodicity of the microfilaremia, we sampled 5 mL of venous blood 4 times daily for 3 consecutive days and counted microfilariae after blood filtration. Blood was collected at fixed times during the day (6:30 am, 12:00 am, 6:00 pm, and 10:30 pm). Microfilariae were detectable in varying densities in all blood samples; counts fluctuated between 13 and 35 microfilariae/mL. On 2 days, the microfilaremia was highest in the evening and lowest in the morning samples, whereas on 1 day, the inverse pattern was observed. Thus, although it seems that microfilaremia substantially fluctuates during the day, this short assessment found no clear circadian rhythm of D. repens microfilaremia (Figure 2). To test for the presence of endosymbionts, we performed a recently published PCR that detects the FtsZ clade of Wolbachia (9). PCRs on microfilariae and adult worm samples were positive. With a goal of curative treatment, we administered doxycycline at 200 mg daily for 4 weeks, followed by a 15-mg dose of ivermectin. The patient fully recovered; eosinophil counts returned to reference ranges and microfilaremia disappeared.

The areas where human subcutaneous dirofilariasis is endemic are increasing, probably because of climate change, host mobility, and global travel (10). Thus, cases are increasing in areas where this disease is not endemic.

We report a case of microfilaremic D. repens infection, which was initially noted as recurrent swelling, in a human. Molecular analysis indicated an Asian genotype of D. repens nematodes, which has also been referred to as Candidatus Dirofilaria hongkongensis. Recurrent swellings are often misdiagnosed, not taken seriously, and therefore diagnosed late. Most cases of human dirofilariasis are diagnosed after surgical removal of the adult nematode and subsequent histologic workup (3). D. repens microfilaremia in humans has been only rarely described (4,5). Several filarial species result in periodic microfilaremia (11), and these fluctuations can be substantial and relevant for diagnosis. Previous studies of dogs have shown that D. immitis and D. repens microfilaremia fluctuates throughout the day and peaks at night (12). Our results showed no clear circadian rhythm, but microfilaremia tended to be higher in the evening, similar to that of canine hosts. However, at time of blood collection, the patient had received the first doses of doxycycline, which might have affected our results.

In our investigation, the adult worm as well as the microfilariae were positive for Wolbachia. Doxycycline targeting this bacterial endosymbiont might thus be a treatment option similar to that for infection with other species of filariae (13). Molecular analysis of adult worms or microfilariae can reveal new genotypes, thereby increasing our knowledge of parasite biology and ecology (9). According to previous reports, D. repens of the Asian genotype is distributed on the Indian subcontinent (14,15). It remains unclear whether some genetic variants differ in their ability to mature and produce microfilaremia in the human host.

Localized subcutaneous swellings, particularly in the periorbital region, are a typical clinical presentation of D. repens infection; however, diagnosis might be difficult because of the absence of microfilaremia, eosinophilia, or positive serologic results. However, if microfilariae are detectable, they display specific features that enable microscopic differentiation. In conclusion, paramount for establishing the diagnosis of D. repens infection of individual patients are in-depth history taking, a high clinical suspicion, and targeted laboratory evaluation.

Dr. Huebl is a resident for tropical medicine at the Department of Tropical Medicine, Bernhard Nocht Institute for Tropical Medicine, and First Department of Medicine, University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany. She is pursuing a PhD in public health degree at the Medical University of Vienna.

Acknowledgment

We thank the patient for providing consent to publish the photograph and clinical data and especially for participating in the periodicity sampling. We also thank Birgit Muntau and Christine Wegner for skillful technical assistance and Jana Held for providing the Wolbachia PCR protocol.

References

- Simón F, Siles-Lucas M, Morchón R, González-Miguel J, Mellado I, Carretón E, et al. Human and animal dirofilariasis: the emergence of a zoonotic mosaic. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2012;25:507–44. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Ermakova LA, Nagorny SA, Krivorotova EY, Pshenichnaya NY, Matina ON. Dirofilaria repens in the Russian Federation: current epidemiology, diagnosis, and treatment from a federal reference center perspective. Int J Infect Dis. 2014;23:47–52. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Pampiglione S, Rivasi F, Angeli G, Boldorini R, Incensati RM, Pastormerlo M, et al. Dirofilariasis due to Dirofilaria repens in Italy, an emergent zoonosis: report of 60 new cases. Histopathology. 2001;38:344–54. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Potters I, Vanfraechem G, Bottieau E. Dirofilaria repens nematode infection with microfilaremia in traveler returning to Belgium from Senegal. Emerg Infect Dis. 2018;24:1761–3. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Kłudkowska M, Pielok Ł, Frąckowiak K, Masny A, Gołąb E, Paul M. Dirofilaria repens infection as a cause of intensive peripheral microfilariemia in a Polish patient: process description and cases review. Acta Parasitol. 2018;63:657–63. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Lechner AM, Gastager H, Kern JM, Wagner B, Tappe D. Case report: successful treatment of a patient with microfilaremic dirofilariasis using doxycycline. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2020;102:844–6. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Liotta JL, Sandhu GK, Rishniw M, Bowman DD. Differentiation of the microfilariae of Dirofilaria immitis and Dirofilaria repens in stained blood films. J Parasitol. 2013;99:421–5. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Casiraghi M, Bain O, Guerrero R, Martin C, Pocacqua V, Gardner SL, et al. Mapping the presence of Wolbachia pipientis on the phylogeny of filarial nematodes: evidence for symbiont loss during evolution. Int J Parasitol. 2004;34:191–203. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Sandri TL, Kreidenweiss A, Cavallo S, Weber D, Juhas S, Rodi M, et al. Molecular epidemiology of Mansonella species in Gabon. J Infect Dis. 2021;223:287–96. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Capelli G, Genchi C, Baneth G, Bourdeau P, Brianti E, Cardoso L, et al. Recent advances on Dirofilaria repens in dogs and humans in Europe. Parasit Vectors. 2018;11:663. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Hawking F. The 24-hour periodicity of microfilariae: biological mechanisms responsible for its production and control. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1967;169:59–76. DOIGoogle Scholar

- Ionică AM, Matei IA, D’Amico G, Bel LV, Dumitrache MO, Modrý D, et al. Dirofilaria immitis and D. repens show circadian co-periodicity in naturally co-infected dogs. Parasit Vectors. 2017;10:116. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Taylor MJ, Hoerauf A, Townson S, Slatko BE, Ward SA. Anti-Wolbachia drug discovery and development: safe macrofilaricides for onchocerciasis and lymphatic filariasis. Parasitology. 2014;141:119–27. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Winkler S, Pollreisz A, Georgopoulos M, Bagò-Horvath Z, Auer H, To KK, et al. Candidatus Dirofilaria hongkongensis as causative agent of human ocular filariosis after travel to India. Emerg Infect Dis. 2017;23:1428–31. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Poppert S, Hodapp M, Krueger A, Hegasy G, Niesen WD, Kern WV, et al. Dirofilaria repens infection and concomitant meningoencephalitis. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009;15:1844–6. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

Figures

Cite This ArticleOriginal Publication Date: May 07, 2021

1These senior authors contributed equally to this article.

Table of Contents – Volume 27, Number 6—June 2021

| EID Search Options |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Please use the form below to submit correspondence to the authors or contact them at the following address:

Lena Huebl, Department of Tropical Medicine, Bernhard Nocht Institute for Tropical Medicine, and First Department of Medicine, University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf, Martinistraße 52, 20246 Hamburg, Germany

Top