Volume 28, Number 10—October 2022

Research

Plasmodium falciparum pfhrp2 and pfhrp3 Gene Deletions and Relatedness to Other Global Isolates, Djibouti, 2019–2020

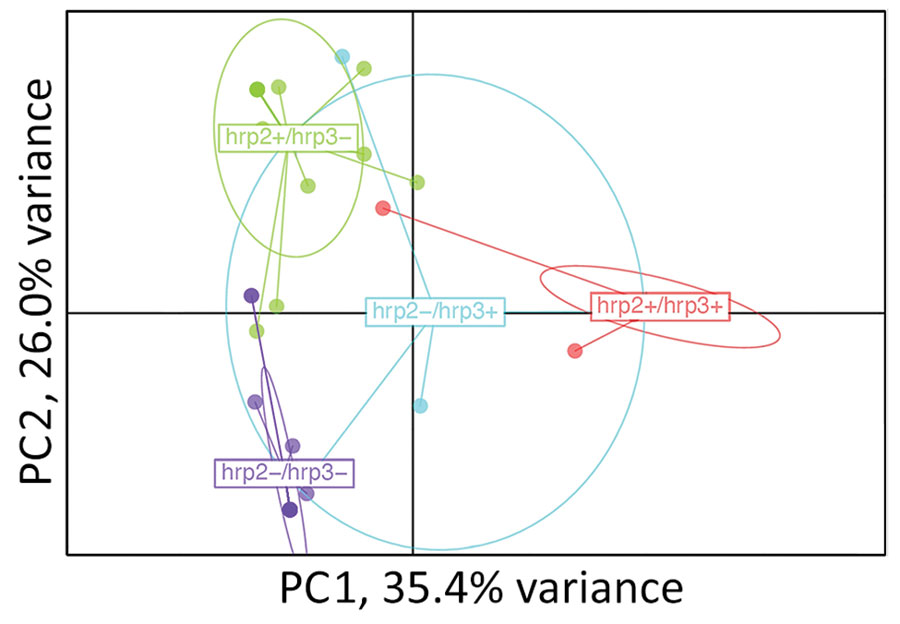

Figure 3

Figure 3. Relatedness of Plasmodium falciparum parasites from Djibouti, 2019–2020, with different pfhrp2 and pfhrp3 genotypes. Cluster PC analysis shown for 7 neutral microsatellite data for monogenomic infections by subpopulations: pfhrp2+/pfhrp3+ (n = 16), pfhrp2+/pfhrp3– (n = 15), pfhrp2–/pfhrp3+ (n = 4), pfhrp2–/pfhrp3– (n = 17). Plot shown with PC1 on x-axis and PC2 on y-axis with 95% confidence ellipses. PC, principal component.

1These authors contributed equally to this article.

Page created: August 11, 2022

Page updated: September 20, 2022

Page reviewed: September 20, 2022

The conclusions, findings, and opinions expressed by authors contributing to this journal do not necessarily reflect the official position of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, the Public Health Service, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, or the authors' affiliated institutions. Use of trade names is for identification only and does not imply endorsement by any of the groups named above.